ABOUT HOW ADAM SMITH CAN CHANGE YOUR LIFE

‘Adam Smith may have become the patron saint of capitalism after he penned his most famous work, The Wealth of Nations. But few people know that when it came to the behavior of individuals—the way we perceive ourselves, the way we treat others, and the decisions we make in pursuit of happiness—the Scottish philosopher had just as much to say. He developed his ideas on human nature in an epic, sprawling work titled The Theory of Moral Sentiments.

Most economists have never read it, and for most of his life, Russ Roberts was no exception. But when he finally picked up the book by the founder of his field, he realized he’d stumbled upon what might be the greatest self-help book that almost no one has read.

In How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life, Roberts examines Smith’s forgotten masterpiece, and finds a treasure trove of timeless, practical wisdom. Smith’s insights into human nature are just as relevant today as they were three hundred years ago. What does it take to be truly happy? Should we pursue fame and fortune or the respect of our friends and family? How can we make the world a better place? Smith’s unexpected answers, framed within the rich context of current events, literature, history, and pop culture, are at once profound, counterintuitive, and highly entertaining.’- See more and purchase the book

This is the Book that the economists by and large have never read

And this is why, by and large, the discipline is in such a mess and is not trusted

A forgotten book by one of history’s greatest thinkers reveals the surprising connections between happiness, virtue, fame, and fortune

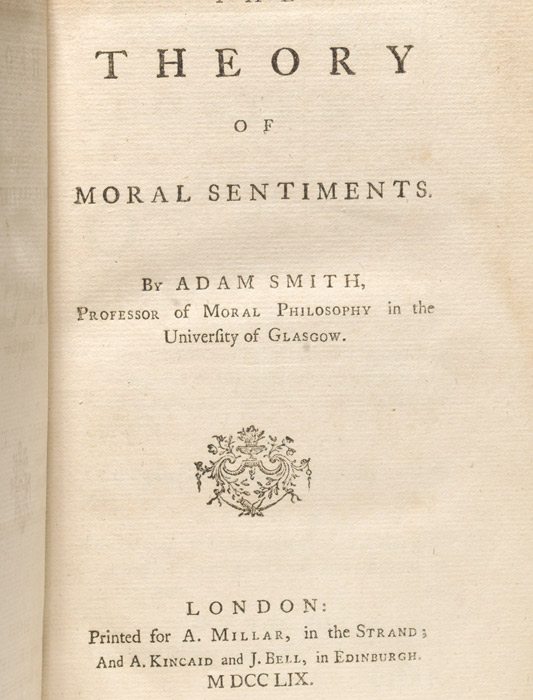

SMITH, Adam. The Theory of Moral Sentiments. London: Printed for A. Millar, in the Strand; And A. Kincaid and J. Bell, in Edinburgh, 1759.-Photo:baumanrarebooks.com

‘Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments laid the foundation on which The Wealth of Nations was later to be built and proposed the theory which would be repeated in the later work: that self-seeking men are often “led by an invisible hand… without knowing it, without intending it, to advance the interests of the society.” “The fruit of his Glasgow years… The Theory of Moral Sentiments would be enough to assure the author a respected place among Scottish moral philosophers, and Smith himself ranked it above the Wealth of Nations…. Its central idea is the concept, closely related to conscience, of the impartial spectator who helps man to distinguish right from wrong. For the same purpose, Immanuel Kant invented the categorical imperative and Sigmund Freud the superego” (Niehans, 62). With Moral Sentiments and Wealth of Nations Smith created “not merely a treatise on moral philosophy and a treatise on economics, but a complete moral and political philosophy, in which the two elements of history and theory were to be closely conjoined” (Palgrave III, 412-13). To Smith when man pursues “his own private interests, the original and selfish sentiments of Theory of Moral Sentiments, he will, in the economic realm, choose those endeavors which will best serve society. Herein lies the connection between the two great works which make them the work of a single and largely consistent theorist” (Paul, “Adam Smith,” 293).

In his Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith develops an ethics based on a “unifying principle—in this case, of sympathy—which would shed light on the harmonious and beneficial order of the moral world. As such it was of considerable interest to Smith’s contemporaries who were groping for an ethics that would flow from man’s impulses or sentiments rather than from his reason, from ‘innate ideas,’ or from theological precepts. If Smith had written only The Theory of Moral Sentiments, he would enjoy in the philosophers hall of fame a niche not unlike that reserved for Shaftesbury or Hutcheson.” Both Moral Sentiments and Wealth of Nations reflect Smith’s “attempt to anchor the new science of political economy in a Newtonian universe, mechanical albeit harmonious and beneficial, in which society is shown to benefit from the unintended consequences of the pursuit of individual self-interest. There is thus a considerable affinity between the structure of The Theory of Moral Sentiments and that of The Wealth of Nations. Each work is integrated by a great unifying principle. What sympathy accomplishes in the moral world, self-interest does in the economic one. Either principle, in its respective realm, is shown to produce a harmony such as the one that characterizes Newton’s order of nature… Smith’s ethics is one of self-command or self-reliance, just as is his laissez faire economics…. Smith’s ethics and his economics are integrated by the same principle of self-command, or self-reliance, which manifests itself in economics in laissez faire” (Spiegel, Growth of Economic Thought, 229-231)’.-Bauman Rare Books

Nota bene

Where does my economic thinking come from? Who inspires me to say what I say? My economic guru is the real Adam Smith, not the false one taught at universities the world over. Let me explain:

‘As many observers, including some honest economists themselves have noted, the economics profession was arguably the first casualty of the 2008-2009 global financial crises. After all, its practitioners failed to anticipate the calamity, and many appeared unable to say anything useful when the time came to formulate a response.

Mainstream economic models were discredited by the crisis because they simply did not admit of its possibility. Moreover, training that prioritised technique over intuition and theoretical elegance over real-world relevance did not prepare economists to provide the kind of practical policy advice needed in exceptional circumstances.

Some argue that the solution is to return to the simpler economic models of the past, which yielded policy prescriptions that evidently sufficed to prevent comparable crises. Others insist that, on the contrary, effective policies today require increasingly complex models that can more fully capture the chaotic dynamics of the twenty-first-century economy.

Why this debate misses the key point. Because, it was not, and it is not about the models to begin with. It is all about what economics was and what it has become. It is all about the missing values in the so-called modern economics.

As a “Recovered” economist, who has seen the “Light” and hopefully is now wiser than before, I believe I can shed some light on this matter.

‘These days I am inspired by the “Real” and “True” Adam Smith, known the world over as the Father of New Economics. We should recall the wisdom of Adam Smith, who was a great moral philosopher first and foremost. In 1759, sixteen years before his famous Wealth of Nations, he published The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which explored the self-interested nature of man and his ability nevertheless to make moral decisions based on factors other than selfishness. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith laid the early groundwork for economic analysis, but he embedded it in a broader discussion of social justice and the role of government. Today we mainly know only of his analogy of the ‘invisible hand’ and refer to him as defending free markets; whilst ignoring his insight that the pursuit of wealth should not take precedence over social and moral obligations.

We are taught that the free market as a ‘way of life’ appealed to Adam Smith but not that he thought the morality of the market could not be a substitute for morality for society at large. He neither envisioned nor prescribed a capitalist society, but rather a ‘capitalist economy within society, a society held together by communities of non-capitalist and non-market morality’. As it has been noted, morality for Smith included neighbourly love, an obligation to practice justice, a norm of financial support for the government ‘in proportion to [one’s] revenue’, and a tendency in human nature to derive pleasure from the good fortune and happiness of other people.

He observed that lasting happiness is found in tranquillity as opposed to consumption. In their quest for more consumption, people have forgotten about the three virtues Smith observed that best provide for a tranquil lifestyle and overall social well-being: justice, beneficence (the doing of good; active goodness or kindness; charity) and prudence (provident care in the management of resources; economy; frugality).

I am very sorry that, no one taught me these when I was a student of economics, and then, I did not tell the truth about Adam Smith to my students when I became an economics lecturer; something that I very much regret and something that am trying hard to rectify, now that I am a “Recovering and Repenting” economist for the common good. At the end of the day, it is our honesty, humility and our struggle to seek the truth that will set us free and allow us to hold our head high.’...Economics, Globalisation and the Common Good: A Lecture at London School of Economics

Imaging a Better World: Moving forward with the real Adam Smith