School of Economic Science, London

Economics with Justice Lecture Series

Saturday 8 February 2014

“A Better Path”

Prof. Kamran Mofid

Abstract:

"The current global crises are not only economic but also spiritual and moral. Therefore, we should not consider tackling the socio-economic and ecological crises without firstly taking into account the moral and spiritual shortcomings that are afflicting the world today. Without the urgent transformation of our socio-economic and political systems, our species and our planet face catastrophe. What is first needed is truer and deeper understanding of our essential kinship with nature and all living things. This, in turn will allow justice and dignity to flourish and pave the way for the development of a sustainable path to a brighter future.”

(This presentation is dedicated to the youth of the world, our children and grand- children, who are the unfolding story of the decades ahead.

May they rise to the challenge of leading the world, with hope and wisdom in the interest of the common good, to change our troubled world for the better)

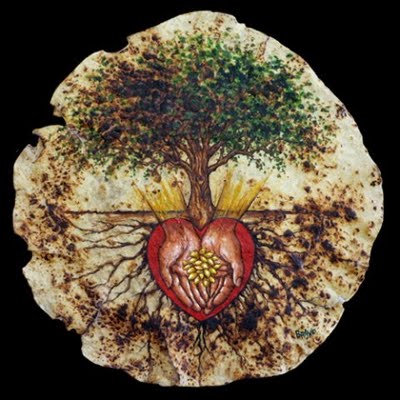

coolgraphic.org

Dear Friends, Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is wonderful to be back in London and the School of Economic Science. We gather here at the kind invitation of SES and the Economic with Justice Lecture Series, grateful for their warm hospitality, support and encouragement.

Before anything else, I wish to give all present in this hall a gift from my heart, in the form of a great Celtic blessing:

The Warmth of the sun to you

The Light of the moon to you

The Silver of the stars to you

The Breath of the wind to you

And the Peace of the Peace to you

And now to my presentation: “A Better Path: Globalisation for the Common Good as a Path to a Just and Sustainable World.”

Let me set the scene by reading you a few inspiring quotes to focus our minds on life’s bigger picture, what’s important, who we are and what is it that makes us truly human:

“He that seeks the good of the many seeks in consequence his own good.” St. Thomas Aquinas

"What is the essence of life? To serve others and to do good." Aristotle

'UBUNTU': "I am because we are.”

“A generous heart, kind speech, and a life of service and compassion are the things which renew humanity.” Buddha

“Try not to become a man of success, but a man of value” Albert Einstein

“Our poverty in the West is not that of the wallet but rather that of social connectedness.” James R. Doty, M.D. Founder and Director of the Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education at Stanford University

The Dalai Lama was once asked what surprised him most. He replied: "Man, because he sacrifices his health in order to make money. Then he sacrifices money to recuperate his health. And then he is so anxious about the future that he does not enjoy the present; the result being that he does not live in the present or the future. He lives as if he is never going to die, and then dies having never really lived."

Now let me share with you the words and sentiments of a young executive, a CEO, earning a lot of money, with bonuses, power, and more: “Now it's all about Productivity, Pay, Performance and Profit - the four Ps – which are fuelled by the three Fs: Fear, Frustration and Failure. Just sometimes I wish that in the midst of these Ps (& Fs), there was some time left for another set of four Fs: Families, Friends, Festivals and Fun.”

You see ladies and gentlemen, we need values, we need love, friendship, kindness, generosity, sympathy, empathy, and compassion to be the guiding principles of all we do. Otherwise, no amount of money, capital, technology, IT, theories and policies, can save us from our own mistakes, the crises of our own making.

In this presentation and conversation afterwards, I will attempt to shed some light on these and other matters and questions in my quest to offer you a path to a just and sustainable world.

I also wish you to note that, this presentation is not addressed to those who regard a practical problem merely as something to be talked about. No profound philosophy or deep erudition will be found in this address. I only aim at putting together some remarks which are inspired by what I hope is common sense, and mostly further inspired by the wisdom of those before me. I have learnt much from the wisdom of others, which I hope to share with you. All that I claim for the recipes offered to you is that they are as such confirmed by my own experience, observation, and most importantly, by my life journey, both personally and professionally. On this basis I venture to hope that some among those thinking about the same and other related issues may find my contribution useful, whilst hoping that our debate and dialogue will be helpful in initiating debate on reconstructing the common good in economics, business, finance, international relation, education and more.

Moreover, I will present my thoughts in an easy-to-follow manner and I see myself as a story-teller in a heart-to-heart dialogue and conversation with you; nothing less, nothing more.

Before I venture out more, let me share with you the philosophy, the vision and values of my educational belief. Here I am most humbly inspired by Lao Tzu, a mystic philosopher of ancient China, considered the founder of Taoism.

He said:

"Some say that my teaching is nonsense. Others call it lofty but impractical.

But to those who have looked inside themselves, this nonsense makes perfect sense.

And to those who put it into practice,

this loftiness has roots that go deep.

I have just three things to teach:

simplicity, patience, compassion.

These three are your greatest treasures.

Simple in actions and in thoughts,

you return to the source of being.

Patient with both friends and enemies,

you accord with the way things are.

Compassionate toward yourself, You reconcile all beings in the world."

Ladies and gentlemen, now let me offer you some reflection on what I mean by Justice, charity, economic justice and the common good, again to focus our minds.

Defining Justice

One definition of justice is "giving to each what he or she is due." However, the problem is to know what is "due". More on this later.

Functionally, "justice" is a set of universal principles which guide people in judging what is right and what is wrong, no matter what culture and society they live in. Justice is one of the four "cardinal virtues" of classical moral philosophy, along with courage, temperance (self-control) and prudence (efficiency). (Faith, hope and charity are considered to be the three "religious" virtues.) Virtues or "good habits" help individuals to develop fully their human potentials, thus enabling them to serve their own self-interests as well as work in harmony with others for their common good.

The ultimate purpose of all the virtues is to elevate the dignity and sovereignty of the human person.

Distinguishing Justice from Charity

Whilst often confused, justice is distinct from the virtue of charity. Charity, derived from the Latin word caritas, or "divine love," is the soul of justice. Justice supplies the material foundation for charity.

Charity offers expedients during times of hardship. Charity compels us to give to relieve the suffering of a person in need. The highest aim of charity is the same as the highest aim of justice: to elevate each person to where he does not need charity but can become charitable himself.

True charity involves giving without any expectation of return. But it is not a substitute for justice, nor a substitute for being a just person.

Defining Economic Justice

Economic justice, which touches the individual person as well as the social order, encompasses the moral principles which guide us in designing our economic institutions. These institutions determine how each person earns a living, enters into contracts, exchanges goods and services with others and otherwise produces an independent material foundation for his or her economic sustenance. The ultimate purpose of economic justice is to free each person to engage creatively in the unlimited work beyond economics, that of the mind and the spirit.

Defining the Common Good

Put it very simply, the common good has origins in the beginnings of Christianity. An early church father, John Chrysostom (c. 347–407), once wrote: “This is the rule of most perfect Christianity, its most exact definition, its highest point, namely, the seeking of the common good . . . for nothing can so make a person an imitator of Christ as caring for his neighbours.” Of course, all other religions say that we are indeed our neighbour’s keeper, and one way or other have time-honoured traditions on the common good.

From a non-religious perspective, in modern political times, the term "common good" is closely associated with the 17th-century British philosopher John Locke, who argued that when people enter a society they give up some liberties to gain protection of a larger set of liberties and rights as part of a social contract. A society knitted together by the common good guarantees rights that would not exist in a pre-social setting. Locke used this explanation to rationalise the establishment of a parliamentary government that would be responsible for assuring the public welfare. Indeed, for example, in the American Constitution itself, the notion of the common good is clearly adhered to when it notes that government should promote “the general welfare.”

Perhaps given your past experiences of listening to the masters and practitioners of the “dismal science”, who have brought us such a bitter harvest, you may now be asking yourselves: Who is this Professor, what kind of economist is he? He is not telling us how to make loads of money, or how to take our money off-shore, but is talking about love, kindness, generosity and the common good! What a strange economist he is! What’s wrong with him! Quite!

Let me explain, as I strongly believe that unless you know the messenger well, first and foremost, then, his message would not make any sense at all.

Given the time constraint today, the best I can do is to quote you a passage from a book I wrote in 2005, well before the crash of September 2008 and very relevant to our discussion and debate today:

“From 1980 onwards, for the next twenty years, I taught economics in universities, enthusiastically demonstrating how economic theories provided answers to problems of all sorts. I got quite carried away by the beauty, the sophisticated elegance, of complicated mathematical models and theories. But gradually I started to have an empty feeling.

‘I began to ask fundamental questions of myself. Why did I never talk to my students about compassion, dignity, comradeship, solidarity, happiness, spirituality – about the meaning of life? We never debated the biggest questions. Who are we? Where have we come from? Where are we going to?

‘I told them to create wealth, but I did not tell them for what reason. I told them about scarcity and competition, but not about abundance and co-operation. I told them about free trade, but not about fair trade; about GNP – Gross National Product – but not about GNH – Gross National Happiness. I told them about profit maximisation and cost minimisation, about the highest returns to the shareholders, but not about social consciousness, accountability to the community, sustainability and respect for creation and the creator. I did not tell them that, without humanity, economics is a house of cards built on shifting sands.

‘These conflicts caused me much frustration and alienation, leading to heartache and despair. I needed to rediscover myself and real-life economics. After a proud twenty-year or so academic career, I became a student all over again. I would study theology, philosophy and ethics, disciplines nobody had taught me when I was a student of economics and I did not teach my own students when I became a teacher of economics.

‘It was at this difficult time that I came to understand that I needed to bring spirituality, compassion, ethics and morality back into economics itself, to make this dismal science once again relevant to and concerned with the common good.’

As an economist ladies and gentlemen, with a wide range of experience, I do appreciate the significance of economics, politics, trade, banking, insurance and commerce, and of globalisation. I understand the importance of wealth creation. But wealth must be created for the right reasons.

Value-led wealth creation for the purpose of value-led expenditure and investment is to be encouraged and valued. Blessed are those wealth creators who know “Why” and “How” wealth is produced and, more importantly, when wealth is created “What” it is going to be used for.

Today’s business leaders are in a unique position to influence what happens in society for years to come. With this power comes monumental responsibility. They can choose to ignore this responsibility, and thereby exacerbate problems such as economic inequality, environmental degradation and social depravation, but this will compromise their ability to do business in the long run. The world of good business needs a peaceful and just world in which to operate and prosper: A world that is truly for the common good.

However, in order to arrive at this peaceful and prosperous destination, we need to change the house of neo-classical economics, to make a fit home for the common good. After all, many of the issues that people struggle over, or their governments put forward, have ultimately economics at their core. As I mentioned before, the creation of a stable society in today’s global world is largely ignored in favour of economic considerations of minimising costs and maximising profits, while other equally important values are put aside and ignored.

Economics once again must find its heart, soul and spirit. Moreover, it should also reconnect itself with its original source, rooted in ethics and morality. Today’s huge controversy which surrounds much of the economic activity and the business world is because they do not adequately and appropriately address the needs of the global collective and the powerless, marginalised and excluded. This, surely, in the interest of all, has to change. The need for an explicit acknowledgment of true global values is the essential requirement in making economics work for the common good. Economics, as practiced today cannot claim to be for the common good. In short, a revolution in values is needed, which demands that economics and business must embrace both material and spiritual values.

Given my observation above, it is very telling and humbling to me to note the Financial Times editorial of November 12, 2013 addressing the same issues as I had made many years ago. Below I have quoted a couple of important and relevant passages:

‘The failure of the dismal science to predict and explain the worst financial crash since the Depression has understandably prompted some reflection among the more thoughtful ranks of academics.

‘The case for new thinking is strong. Economics teaching – even to first-year undergraduates – had before the crisis become too wedded to scientific pretension. Excessive faith was invested in abstract mathematical models, while insufficient effort was made to link these to real-life experience. The absence of topicality not only robbed the subject of interest and excitement, it risked not equipping the student with the skills to grapple with everyday problems.

‘The recital of laws and ritual genuflection towards mathematical models may lend the subject a certain intellectual respectability, but much of this is spurious.

‘There are stirrings in the academic gloaming. The failure to predict the crash not only unsettled Queen Elizabeth II – who famously gathered some economists together to ask them how they had missed it. There has been some soul-searching among academics too.

‘There is a recognition that disciplines such as psychology, history and finance need to be more firmly embedded in economics teaching. The route to publication in top journals should involve empirical research, not just the firing up of an Excel spreadsheet.

‘But, as the crisis showed, we should be humble about the limits of our knowledge. Substituting a little humility for pretension would be a welcome step.’

Well said. However, what a great pity that to the best of my knowledge, influential publications, such as the Financial Times, had not written an editorial in similar vein before the crash of September 2008. I believe our world would have been a better place for it if they had.

For example, perhaps people like the Director of the London School of Economics and his colleagues at the department of economics would have behaved differently, and would have acted with wisdom, courage, and commitment to the common good.

In support of the above, we couldn’t have clearer evidence than Lord Kalms’ letter to the Times (08/03/2011):

Ethics boys

Sir, Around 1991 I offered the London School of Economics a grant of £1 million to set up a Chair in Business Ethics. John Ashworth, at that time the Director of the LSE, encouraged the idea but had to write to me to say, regretfully, that the faculty had rejected the offer as it saw no correlation between ethics and economics. Quite.

Lord Kalms, House of Lords

Thus, ladies and gentlemen, by now it must be clear that, given the state of our world today- a world of progress and poverty- the continuing and deepening global economic turmoil merely is a symptom of a much larger moral, spiritual and ethical crisis. In short, the world is facing a crisis of values.

There is no doubt that, we should see this multitude of crises as a wakeup call to action, to see things as they are. We should search with an open mind for the wisdom we need to transform our economic system to a sustainable path, grounded in ecological reality, with respect for justice and dignity for all, and our appreciation for nature and our kinship for all living things.

Time is Now for Radical Change: What is to be done?

At a time during the American Revolution, when things looked very dire and impossible, Tom Paine wrote:

"These are the times that try men's souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and women. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. . . ”

As many round the world are saying loud and clear, “This is another of those times. Our souls are being tried. This is our opportunity to stand firm, to show our perseverance and fortitude. This is a time our children and grandchildren will sing about. Their ballads will praise us for bringing them the world we all deserve.”

Thus, it is time to question the functionality of the existing economic system that has created a massive and widening gap between a few super rich and the many in abject poverty. We need to examine the soundness of extracting growing profit from a highly leveraged and unsustainable real sector in the face of massive numbers of disenfranchised people who are deprived of a potentially prosperous economic life. We need to question the ability of mother earth to support the extravagance of our blind and ignorant consumerism. We also need to put self interest in perspective, and balance it with concern for the common good and for other species and the earth.

We should recall the wisdom of Adam Smith, “father of modern economics”, who was a great moral philosopher first and foremost. In 1759, sixteen years before his famous Wealth of Nations, he published The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which explored the self-interested nature of man and his ability nevertheless to make moral decisions based on factors other than selfishness. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith laid the early groundwork for economic analysis, but he embedded it in a broader discussion of social justice and the role of government. Today we mainly know only of his analogy of the ‘invisible hand’ and refer to him as defending free markets; whilst ignoring his insight that the pursuit of wealth should not take precedence over social and moral obligations.

We are taught that the free market as a ‘way of life’ appealed to Adam Smith but not that he thought the morality of the market could not be a substitute for the morality for society at large. He neither envisioned nor prescribed a capitalist society, but rather a ‘capitalist economy within society, a society held together by communities of non-capitalist and non-market morality’. As it has been noted, morality for Smith included neighbourly love, an obligation to practice justice, a norm of financial support for the government ‘in proportion to [one’s] revenue’, and a tendency in human nature to derive pleasure from the good fortune and happiness of other people.

In his "Theory of Moral Sentiments" he observed that "How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it."

In all, building a new economics system will demand challenging and novel ways of thinking, perspectives that encompass the broad swath of human experience and wisdom, from the natural sciences and all the social sciences, to the philosophical and spiritual values of the world’s major religions and of indigenous peoples as well. The task before us is a daunting one, and wisdom in how to proceed will come from a multiple of sources, and must embrace the panorama of cultural and disciplinary perspectives. Let us not carry on constructing a global society that is materially rich but spiritually poor. Let us begin to construct globalisation for the common good, as a path to construct a just and sustainable world.

Globalisation for the Common Good Initiative (GCGI): Where we connect our intellect with our humanity

To understand, appreciate, and face the challenges of the contemporary world requires us to focus on life’s big picture. Whether it is war and peace, economics and the environment, justice and injustice, love and hatred, cooperation and competition, common good and selfishness, science and technology, progress and poverty, profit and loss, food and population, energy and water, disease and health, education and family, we need the big picture in order to understand and solve the many pressing problems, large and small, regional or global.

The “Big Picture” is also the context in which we can most productively explore the big perennial questions of life - purpose and meaning, virtues and values.

In order to focus on life’s bigger picture and guided by the principles of hard work, commitment, volunteerism and service; with a great passion for dialogue of cultures, civilisations, religions, ideas and visions, at an international conference in Oxford in 2002 the Globalisation for the Common Good Initiative (GCGI) and the GCGI Annual International Conference Series were founded.

We recognise that our socio-economic problems are closely linked to our spiritual problems and vice versa. Moreover, socio-economic justice, peace and harmony will come about only when the essential connection between the spiritual and practical aspects of life is valued. Necessary for this journey is to discover, promote and live for the common good. The principle of the common good reminds us that we are all really responsible for each other – we are our brothers' and sisters' keepers – and must work for social conditions which ensure that every person and every group in society is able to meet their needs and realize their potential. It follows that every group in society must take into account the rights and aspirations of other groups, and the well-being of the whole human family.

One of the greatest challenges of our time is to apply the ideas of the global common good to practical problems and forge common solutions. Translating the contentions of philosophers, spiritual and religious scholars and leaders into agreement between policymakers and nations is the task of statesmen and citizens, a challenge to which Globalisation for the Common Good Initiative (GCGI) adheres. The purpose is not simply talking about the common good, or simply to have a dialogue, but the purpose is to take action, to make the common good and dialogue work for all of us, benefiting us all.

What the GCGI seeks to offer - through its scholarly and research programme, as well as its outreach and dialogue projects - is a vision that positions the quest for economic and social justice, peace and ecological sustainability within the framework of a spiritual consciousness and a practice of open-heartedness, generosity and caring for others. All are thus encouraged by this vision and consciousness to serve the common good.

The GCGI has from the very beginning invited us to move beyond the struggle and confusion of a preoccupied economic and materialistic life to a meaningful and purposeful life of hope and joy, gratitude, compassion, and service for the good of all.

Perhaps our greatest accomplishment has been our ability to bring Globalisation for the Common Good into the common vocabulary and awareness of a greater population along with initiating the necessary discussion as to its meaning and potential in our personal and collective lives.

In short, at Globalisation for the Common Good Initiative we are grateful to be contributing to that vision of a better world, given the goals and objectives that we have been championing since 2002. For that we are most grateful to all our friends and supporters that have made this possible.

In conclusion, I wish to invite you all to rise to the global challenges and uncertainties. Many campaigners for a better world, wishing to serve and to promote the common good, often face an uphill battle every day.

But, we must remain positive, we must remain hopeful. We will build the World for the Common Good. We will.

Today, here in London, in this place committed to learning, teaching and activism for the common good, we formed a community of committed and passionate gardeners, sowing seeds of sustainability, peace, justice and global friendship for the common good. In the wonderful and wise words of Rumi:

Tender words we spoke

to one another

are sealed

in the secret vaults of heaven.

One day like rain,

they will fall to earth

and grow green

all over the world.

Photo: wordpress.com