We are more than taxpayers!

Taxes, if informed by the common good, can be a positive way to fulfill our calling to do public justice. Photo:bing.com

These days, led by neoliberalism, we are more likely to hear ourselves referred to as “taxpayers” than “citizens.” What if we viewed ourselves as citizens first? We might stop asking “what’s in it for me?” and begin to ask “what’s in it for everyone?”

As it has been noted by many with an eye on justice, fairness and the common good, ‘Taxes raise the revenues used to pay for democratic institutions and to provide government programmes and services. Taxes can also be used to promote other economic and social policy goals through the use of tax expenditures. Over the past decade, significant changes have been made to our tax system, including deep cuts to tax rates. The impact of these changes is cause for concern: there has been a significant loss or erosion of public services that benefit us all, a loss of progressivity in the tax system, and growing income inequality between the rich and the poor with significant costs and consequences for all.

At the same time, there has been an erosion of democratic control and accountability for taxation and public spending. The context for debate has also been very hostile to an open and honest conversation about taxes and the services they pay for. A more positive perspective on taxes views them as an important part of citizenship and democratic representation and a contribution to the common good.

A related perspective views taxes as dues paid in recognition of the common wealth each citizen benefits from, passed on by earlier generations. Taxes can also represent a form of income redistribution over the course of an individual lifetime, as well as an efficient and effective way for individuals to procure services by doing so collectively. Taxes are also an important form of income redistribution in society.

Taxes are one way in which we as citizens fulfil our obligation to promote justice and to respect the right of all people to live in dignity. For governments, tax policy can be used to foster justice, in addition to tax revenues paying for infrastructure and public services that benefit all and promote an equitable society. Public justice also supports a progressive distribution of taxes, and transparent and accountable decisions from governments on taxation and spending.’

Following on what was noted above, today I read a very interesting article on how we may be able to explain and understand ‘tax as a force for common good’, which I very much enjoyed reading and thus, would like to share it with you.

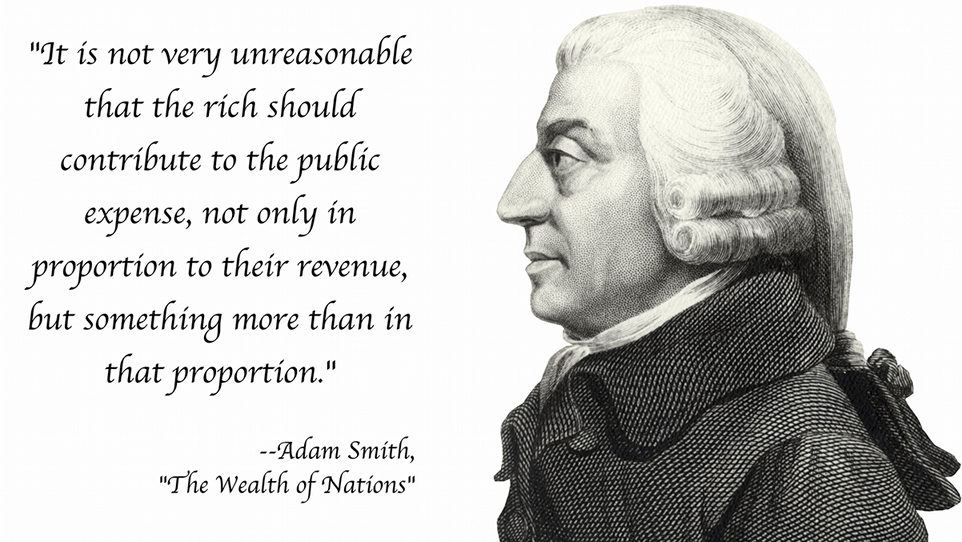

However, in order to appreciate the wisdom of this article, it is necessary to understand and to get-to-know the real Adam Smith. This is important. As the article has highlighted, it is the organisations, such as the Adam Smith Institute, that have poisoned the debate on “Taxation” by using the different Adam Smith, to the one I discovered many years after being a student of economics, or indeed, when I became an economic lecturer. Let me explain a bit more by quoting a passage or two from an article I had written a while back:

Photo: imgur.com

‘These days I am inspired by the “Real” and “True” Adam Smith, known the world over as the Father of New Economics. We should recall the wisdom of Adam Smith, who was a great moral philosopher first and foremost. In 1759, sixteen years before his famous Wealth of Nations, he published The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which explored the self-interested nature of man and his ability nevertheless to make moral decisions based on factors other than selfishness. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith laid the early groundwork for economic analysis, but he embedded it in a broader discussion of social justice and the role of government. Today we mainly know only of his analogy of the ‘invisible hand’ and refer to him as defending free markets; whilst ignoring his insight that the pursuit of wealth should not take precedence over social and moral obligations.

We are taught that the free market as a ‘way of life’ appealed to Adam Smith but not that he thought the morality of the market could not be a substitute for the morality for society at large. He neither envisioned nor prescribed a capitalist society, but rather a ‘capitalist economy within society, a society held together by communities of non-capitalist and non-market morality’. As it has been noted, morality for Smith included neighbourly love, an obligation to practice justice, a norm of financial support for the government ‘in proportion to [one’s] revenue’, and a tendency in human nature to derive pleasure from the good fortune and happiness of other people.

He observed that lasting happiness is found in tranquillity as opposed to consumption. In their quest for more consumption, people have forgotten about the three virtues Smith observed that best provide for a tranquil lifestyle and overall social well-being: justice, beneficence (the doing of good;active goodness or kindness;charity)and prudence (provident care in the management of resources;economy; and frugality).

I am only very sorry that, no one taught me these when I was a student of economics, and then, I did not tell the truth about Adam Smith to my students when I became an economics lecturer; something that I very much regret and something that am trying hard to rectify, now that I am a “Recovering and Repenting” economist for the common good. At the end of the day, it is our honesty, humility and our struggle to seek the truth that will set us free and allow us to hold our head high, nothing less, nothing more.”

Now that I have introduced you to the real Adam Smith, let me share the article I was talking about with you:

‘Let’s talk about tax as a force for common good – or we lose the debate’

‘Tax Freedom Day is another sad example of how our contribution to society is regarded as theft. This cannot go unchecked’

‘For the first 212 days of the year, every penny you’ve earned you’ve kept for yourself. In the meantime, you’ve been enjoying and helping others enjoy the health service for free.’- Photo: bing.com

31 July should have been a day of great civic celebration. For the first 212 days of the year, every penny you’ve earned you’ve kept for yourself. In the meantime, you’ve been enjoying and helping others enjoy the health service, public education, kerbside waste collection, policing, defence, pensions, roads and welfare payments, all for free. Only since Sunday have you started to contribute your share to all these and many more benefits of a modern, developed state.

No one is celebrating such a social solidarity day yet. However, for several years the Adam Smith Institute and the Taxpayers Alliance have been advocating something they call tax freedom day, which fell this year on 3 June. They tout this as “the first day of the year that you start earning money for yourself”, since on average all we earn for 154 days of the year we pay in taxes.

Social solidarity day and tax freedom day are of course two ways of looking at exactly the same objective phenomenon: that on average, 154 calender days earnings are taxed. The meaning of this fact, however, is changed by how we frame it. For economic libertarians, taxation is a deprivation of what is ours by natural right. For those who favour a welfare state, taxation is (or at least should be) a fair payment towards a well-functioning, just society that protects the weak as well as the strong.

Tax freedom day has been an effective rhetorical tool for advancing the tax-as-theft worldview. It is now as politically difficult to speak positively of tax as it is easy to praise the things we spend these taxes on, as though we can be in favour of the NHS while being against what funds it.

The demonisation of tax is part of a wider ideological battle to get us to think more like Americans and less like our fellow Europeans. Government is portrayed not as the servant of the people but as our tyrannical master. The state doesn’t act on our behalf, it interferes in our affairs. We are not governed in but ruled by London and Brussels.

The spread of these ways of thinking have contributed to the decline in trust in politics and disdain for mainstream politics. Countering it is a vital task for all who value anything like European social democracy. This requires reframing the debate around taxation in three key ways.

First, there is the issue of waste and inefficiency in government spending. This is real but often exaggerated. For example, international reports have repeatedly shown that the NHS is one of the most, if not the most, efficient health systems in the world. Where there is waste, however, we increasingly see only an opportunity to cut.

For example, last year the Labour peer Lord Carter led a review which suggested up to £5bn per year could be saved in the NHS through procurement improvements and minimising the use of agency staff. Almost everyone took this as meaning we could spend £5bn less on the NHS when it could equally mean having an extra £5bn to spend expanding services. Time and again the war on waste is waged in the name of tax cuts when it could be fought in the cause of better services.

Second is the issue of fairness. Take the complaint that multinationals operating in the UK pay hardly any tax here. Too often it is assumed that this means that others are paying too little and so we are paying too much. The key problem, however, is simply that taxes that could help run the country are going uncollected. The debate has become one about paying a fair share when it is more importantly one about increasing the size of the pot we pay into.

Third, we need to counter the subtle ways in which we are complicit in the taxophobics’ game. Think about how every newspaper and news outlet reports the budget. The bottom line is always presented in terms of whether tax changes leave specific types of people better or worse off, usually by mere pennies per week. The most important test of a budget should not be how taxes hit individuals’ pockets, but whether overall government is sustainably improving the state of the nation. Taxing less than we need to is as bad as taxing more than is necessary.

These changes in how we think and talk might strike you as modest and uncontroversial. Proof that they are anything but is that a campaign to start celebrating social solidarity day would today be laughed off as some kind of politically correct joke. Unless and until we make it normal to see taxation primarily as a valuable contribution to our own and the common good, the narrative that government is the enemy and tax is theft will continue to prevail.

This article was first published in the Guardian on Monday 1 August 2016.

See the original article:

Let’s talk about tax as a force for common good – or we lose the debate

For further reading see: