- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 7485

Despite being the home of one of the world's most ancient civilisations and cultures, very sadly today modern Iran is one of the world's most misunderstood countries. The significant contribution of this great civilisation to the progressive development of science, technology, arts, architecture, literature, poetry and human rights (The Cyrus the Great Cylinder) and more cannot be over emphasised. Therefore, this confusion and misunderstanding is indeed tragic for all concerned. It goes without saying that a better understanding of Iran and Iranians is an essential pre-requisite for more harmonious international relations and the dialogue of civilisations for the common good.

For a A- Z of Persia and modern Iran, see:

The A-Z of Iran: part I and II

The New Statesman’s A-Z guide to the Islamic Republic of Iran — a complex nation’s rich history, culture, economy and politics:

http://www.newstatesman.com/world-affairs/world-affairs/2012/06/z-iran-part-1

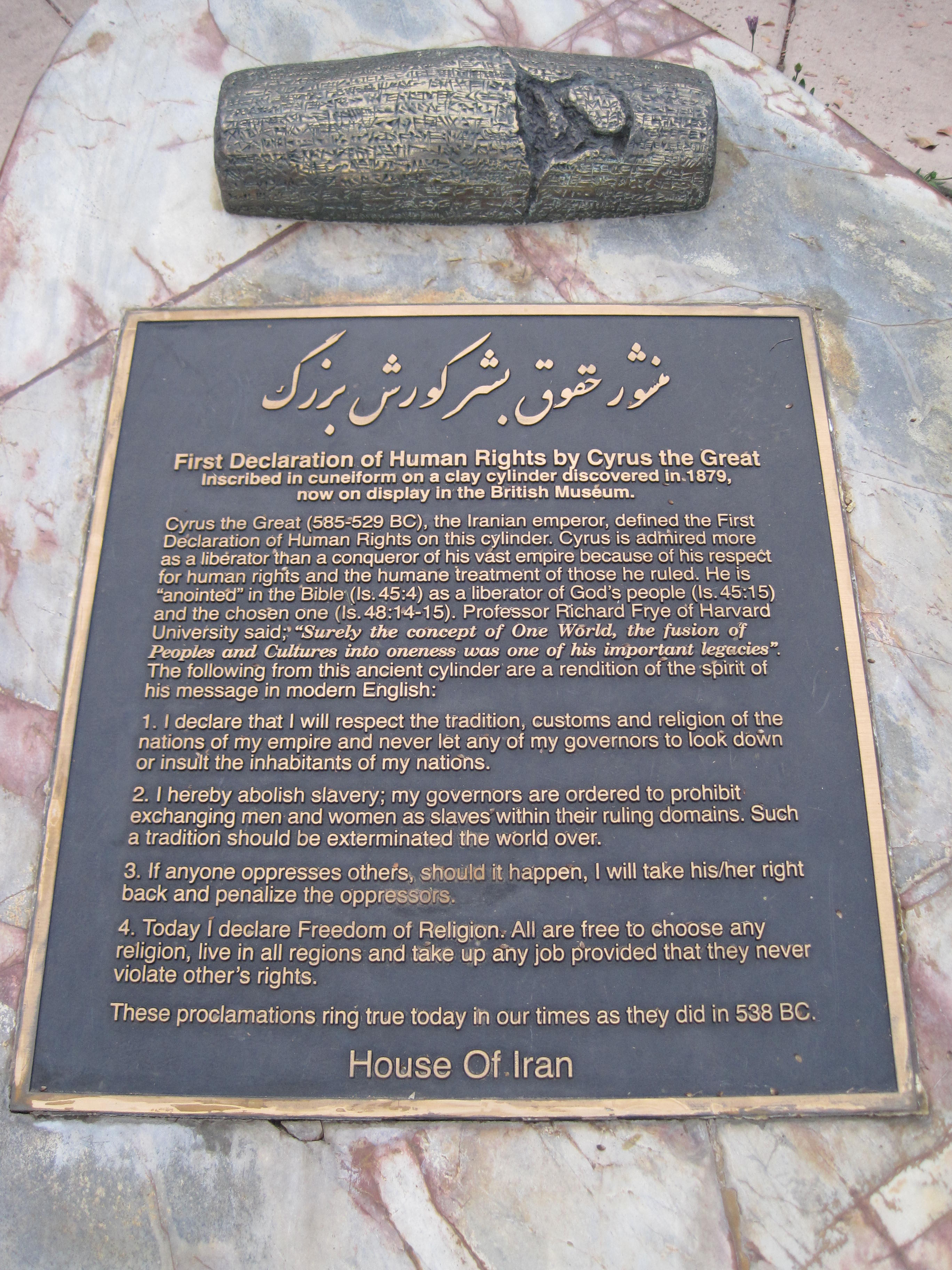

The Cyrus the Great Cylinder

The Cyrus the Great Cylinder is the first charter of right of nations in the world. It is a baked-clay cyliner in Akkadian language with cuneiform script. In 1971, the Cyrus Cylinder was described as the world’s first charter of human rights and it was translated into all six official U.N. languages. A replica of the cylinder is kept at the United Nations Headquarters in New York City in the second floor hallway, between the Security Council and the Economic and Social Council chambers. Passages in the text of cylinder have been interpreted as expressing Cyrus’ respect for humanity, and as promoting a form of religious tolerance and freedom; and as result of his generous and humane policies, Cyrus gained the overwhelming support of his subjects.

Read more: The Cyrus the Great Cylinder

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 4884

Grand Pursuit: the Story of Economic Genius

Reviewed by John Gray

Those familiar with my writings know well about my respect for economics as it was, a branch of moral philosophy, and my scorn and dislike for economics as it has become, a moral/spiritual-free zone. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that I wish to share this excellent book review by John Gray with you. Please find time to read it, and be inspired by it.

“As Nasar demonstrates, the subject has been shaped as much by ideological fantasy and overweening theoretical constructions as by empirical inquiry. Few economists anticipated the financial crisis or believed that a dislocation on the scale the world has suffered was even remotely possible. Equally, because history - even the history of economics - is no longer seen as central to the profession, very few economists have had anything of interest to say about how to deal with the difficulties that have followed. This only confirms the continuing accuracy of Stigler's indictment of a hollow discipline. When you are struggling to stave off a global disaster, there isn't a great deal to economics.”- John Gray

…”There really isn't a great deal to economics, considered as a logical structure based on a few indisputable axioms about the world. If one cuts oneself off from two generations of immensely varied and instructive empirical research, and if one thinks economic history has no relevance to economic theory, then one is indeed left with a hollow discipline."- George Stigler

Writing in 1963, Stigler reached this judgement in a review of Joan Robinson's book Economic Philosophy. Robinson, whom Stigler described as "a superior logician", fused the "indisputable axioms" of economics with the ideological prejudices of the time…

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 7221

(This is the short version of a paper which in its final form will include insights and guidance from other religious, philosophical, and spiritual perspectives)

Steve Szeghi PhD (ECON), Professor of Economics, Wilmington College, Wilmington, Ohio, USA

Jamshid Damooei PhD (ECON), Professor of Economics, California Lutheran University, USA

Kamran Mofid PhD (Econ), Founder, Globalisation for the Common Good Initiative (GCGI), UK

Promised Land Revisited: Forgive our debts as we forgive our debtors

The global economy is in crises, whilst stuck in a consumer debt trap. Consumers and businesses, not to mention local and national governments, are in the dregs of a balance sheet recession. Without increased government spending to mitigate the demand crisis, there’s little chance the economy will jump start on its own.

Whilst we can turn to the trusted Keynesian spending model to fix a balance sheet recession and get consumer spending to kick back in; there is also the old biblical idea of a jubilee - a national cancellation of private debts. We believe forgiveness is the best present we can give ourselves, as it will set us all free.

Contained in what many Christians refer to as the ‘Our Father’ or ‘Lord’s Prayer’, are the following words in some interpretations, “Forgive us our debts as we forgive of debtors”. The words imply that since we owe much to God, that we should stand ready and willing to forgive what others owe to us, and to stand ready to do that every day as the prayer also says, “give us this day our daily bread”. What has happened to the concept of forgiveness of debt? Much of the developing world is saddled with debt service payments that take such a large and substantial portion of GDP that not only is development imperiled, but life itself for a multitude of people in the country is imperiled. While occasionally for many decades now there has been talk of debt forgiveness, little has changed.

From Ireland, to Portugal, to Greece, to Spain, to Italy, throughout Europe and elsewhere there is one sovereign debt crisis after another. Debt forgiveness while spoken about is seldom significant enough to make a difference. In the United States as a result of the financial crisis of 08-09, huge financial institutions were rescued, in some sense forgiven, but there has been little to no relief for the individual homeowner, just as there is little to no relief for individuals who borrow be it in micro credit markets or by more conventional means throughout the world

The global financial and economic system is structured, and it is ever increasingly the case, to resist forgiveness of debt. Creditors bristle at the mere suggestion. The notion of debt forgiveness rankles their inmost being at its very core. But yet we cannot help but to think of the words, “forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors.” In coming to grips with the problems of growing inequality, poverty, continuing financial instability, and stagnant economies, debt forgiveness stands out as a requisite part of the solution. A system that refuses to forgive debt is a system that is essentially siding with creditors, bailing out their bad choices, at the peril of the stability of the system itself, in addition to exacerbating inequality, perpetuating poverty, and stalling the engine of economic progress.

Forgiveness of debt was an essential ingredient of the political economy of the Ancient Hebrews. All debts of fellow Hebrews were to be forgiven in the Sabbatical Year (which occurred every seven years). In addition all slaves who were ‘kinsmen”, were to be set free in the Sabbatical Year. Forgiveness of debt was an essential part of Hebrew society. Debt forgiveness was structured into the system which in turn allowed for social cohesion and unity. Not only were the Ancient Hebrews required to forgive debts in the Sabbatical Year they were required to lend freely even as the sabbatical year grew closer. “Be on guard lest, entertaining the mean thought that the seventh year, the year of relaxation is near, you grudge help to your needy kinsman and give him nothing: else he will cry to the Lord against you and you will be held guilty.” Deuteronomy 15, v 9

Jesus of Nazareth extended this wisdom of the Torah. For Jesus, all human beings, Hebrew and non-Hebrew alike were kinsmen. So for Jesus the tradition of the Torah was extended to all. In addition Jesus instructed those who followed him to lend freely to all, fellow Hebrew or not. His teaching was to be willing to forgive every day, every year, and to lend freely without any care as to whether or not the one you were lending to could pay you back. For Jesus then, every year becomes the Sabbatical Year. In Ancient Israel it is forbidden to charge interest, such was called usury, and in the Christian Middle Ages throughout Europe usury was considered one of the seven deadly sins. Yet here is Jesus of Nazareth not just forbidding the taking of interest but also teaching not to even expect repayment of principal. (Luke chpt 6)

Now we live in a time when interest is charged freely without even any maximum caps (For example it is estimated that a typical annual interest rates (APRs) of between 650% to around 4000% and more is charged by the “Payday” loan companies). We live at a time when an increasing number of people cannot have their debts forgiven, not ever, because they fall in a particular demographic or income category. In the United States today under the new Bankruptcy law passed in the latter years of the George W. Bush Administration, so long as a person makes the average or above income in their state, bankruptcy is increasingly impossible to declare, in the sense of having one’s debts permanently discharged or forgiven. We live in a time when an ever increasing share of total debt, has been placed in a non-forgivable or non-dischargeable category. These types of debts include student loans in the United States, as well as micro-credit loans in many countries.

In the United States for example, those with more than a million dollars in debt are allowed to play by the older more generous bankruptcy rules. So millionaires and corporations are still generously forgiven, and through other means as well, in addition to bankruptcy court. Corporations, and the individuals who run them and benefit the most from them, routinely escape responsibility, but middle class and poor students trying to get through college, there is little to no debt forgiveness for them. The financial system that we have across the globe, a system that resists debt forgiveness, has no caps on interest rates, and no limits on wealth, is unsound on a moral level, and is also unsound on an economic level. The poor countries of the world are mired in debt and need forgiveness. First we experienced the housing bubble. The remedies for that crisis amounted to little or no relief for actual homeowners, and so the effects of that crisis continue to linger. Now we have the sovereign debt crisis of the European countries coupled with the debt burdens of the developing world. Next will come, either the student loan bubble or the credit card bubble, both of which are securitized just as was the case with home mortgages and both will cause just as much damage and instability as the housing crisis. It is time to wipe the slate clean and start fresh and new.

Significant debt forgiveness is clearly called for. But in addition we need a structured and systematic means of forgiveness for debt such as was the case for the people of Ancient Israel. It cannot merely be something that is trotted out on an ad hoc basis to respond to a lingering crisis and its aftermath. It has to be a regular part of the social contract. We need a structured means to limit the accumulation of wealth just as the Ancient Hebrews had with their Jubilee Year. Such means to limit wealth should include both a wealth and an inheritance tax of significant magnitude. While it is likely too ambitious to insist upon interest free lending, caps on interest rates are clearly called for, and in consideration of social justice discounted rates for the poor to provide for their means of support are crucial.

We think creating a clean slate is the only way we can really move forward that does not replicate the past. In looking at Forgiveness on a collective level, we were reminded of this Ancient process of both the Sabbatical Year (the Seventh year) and the Jubilee Year (seven times the Seventh Year). The Jubilee is the Sabbatical of the Sabbatical years. Every Sabbatical year, debt is completely forgiven and the slaves may return home as freed men and women. In the Jubilee Year, not only were debts forgiven and slaves returned home, but all land was to be returned to its original owners. (Leviticus 25) The Jubilee Year functioned as a structural means of redistribution to limit wealth – as most wealth consisted of land at that time in history, so that in the words of Isaiah the rich would not join field to field and leave no room for the poor.

Forgiveness is about release of past wrongs and hatreds. It is the healing of old wounds held deep in the social and personal fabric of our collective and personal bodies. The energy and time wasted in servicing debt is blocking the life force teeming up from the hearts of those who choose to see a new earth.

In theological terms, as a time of Grace, the Jubilee Year provided an opportunity to stop, to listen and to consider. It was an opportunity to enact forgiveness. It marked an occasion—what theologians call a kairos moment— A God-given moment of destiny not to be shied away from but seized with decisiveness; the floodtide of opportunity and demand in which the unseen waters of the future surge down to the present. It’s the alignment of natural and supernatural forces creating an environment for an opening to occur; a time when heaven and earth align with one another in a spiritual sense; a time when heaven touches earth in a way that will never be forgotten, the Promised Land once again.

ABOUT KAMRAN MOFID’s Blog and GUEST BLOG

KAMRAN MOFID’s Blog: Dedicated to the Common Good- aiming to be a source of hope and inspiration; enabling us all to move from despair to hope; darkness to light and competition to cooperation. “Whatever you can do or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it”. —Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

“When we are dreaming alone it is only a dream. When we are dreaming together it is the beginning of reality”. —Helder Camara

KAMRAN MOFID’s GUEST BLOG: Here on The Guest Blog you’ll find commentary, analysis, insight and at times provocation from some of the world’s influential and spiritual thought leaders as they weigh in on critical questions about the state of the world, the emerging societal issues, the dominant economic logic, globalisation, money, markets, sustainability, environment, media, the youth, the purpose of business and economic life, the crucial role of leadership, and the challenges facing economic, business and management education, and more.