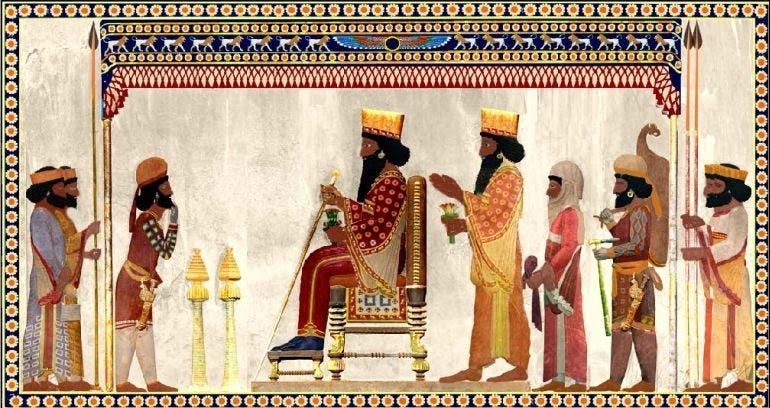

Photo: Via Medium

Photo: Via Medium

Despite being the home of one of the world's most ancient civilisations and cultures, very sadly today, modern Iran is one of the world's most misunderstood countries. The significant contribution of this great civilisation to the progressive development of science, technology, arts, architecture, literature, poetry and human rights and more cannot be over emphasised.

This confusion and misunderstanding is indeed tragic for all concerned. It goes without saying that a better understanding of Iran and Iranians is an essential pre-requisite for more harmonious international relations and the dialogue of civilisations for the common good.

In this blog I wish to bring to your attention a very timely and eloquent book (Spirituality in the Land of the Noble) whichhighlights how Iran has played an unexcelled role in influencing, transforming, and propagating all the world's universal traditions.

Spirituality in the Land of the Noble: How Iran Shaped the World’s Religions

by Richard C. Foltz, Oxford, Oneworld Publications, 2004. 204 pages

Preface:

“When speaking of "cradles of religion" one most commonly thinks of the Near East and South Asia. The role of Iranians in generating and shaping the world's major religious traditions is not less than that of Semites or Indians, but it is less obvious. It is the aim of this book to bring that contribution into the foreground.

Of course Iran today is an overwhelmingly Muslim nation -- about ninety-nine percent of the total population of over seventy million, nine-tenths of whom are Ithna 'Ashari Shi'is. But even in the world's first modern Islamic state there is far more religious diversity than meets the eye at first glance.

The Iranian constitution reserves three seats in Parliament for representatives of the Christian minority, and one seat each for Jews and Zoroastrians. Only Baha'is -- who, numbering as much as half a million or more in Iran, remain the country's largest non-Muslim minority -- are denied official recognition and representation, while Iran's tiny community of ancient Gnostics, the Mandaeans, are hardly known at all.

Modern Iran's relative religious homogeneity notwithstanding, throughout the country's long history its peoples and cultures have played an unexcelled role in influencing, transforming, and propagating all the world's universal traditions.

As I have described in another book, the merchants and missionaries who first brought Judaism, Buddhism, Christianity, Manichaeism, and Islam to China along the Silk Roads were predominantly Iranian. Along the way each of these traditions was dramatically infused with Iranian ideas and interpretations.

Apart from Zoroastrianism, Islam, and the Baha'i faith, the histories of other religions within Iran itself remain largely unexplored, although prior to the Arab conquest in the seventh century much of eastern Iran was Buddhist and much of the western regions Christian. Manichaeism, itself largely an Iranian product, was a major presence there for a number of centuries.

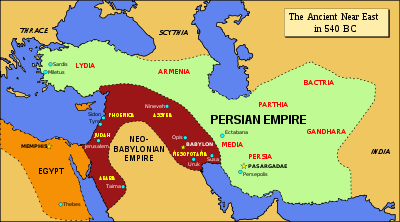

The history of Iranian Judaism, which begins with the fall of Israel to the Assyrians in 722 BCE and subsequent deportations of Israelites to Iranian territories, is one of the least-known aspects of the Jewish Diaspora. The influence of Iranians and specifically Iranian notions in the foggy emergence of Mahayana Buddhism has only very recently begun to be seriously explored by scholars.

And while Christianity's attempts to permeate the world's largest continent appeared by post-Mongol times to have been a spectacular failure (the Christianization of the Philippines and Korea being a more recent phenomenon), centuries earlier the balance between the eastern and western churches was far more even.

For well over a millennium it was the Iranian variant of Christianity that Asians knew and perceived as normative, as the surprised (and dismayed) accounts of William of Rubruck and other early Catholic missionaries make clear.

The role of Iranians in shaping Islam and Muslim civilization -- comparable perhaps to that of Hellenism in the formation of Christianity -- is well understood by specialists but not so much by the general public. To this day most people continue to associate Islam with Arabs and the Near East, despite the fact that in Asia, where three-quarters of the world's Muslims actually live, Islam was received in most cases through a thickly Persian filter.

Finally there is the Baha'i faith, a distinctly modern religious tradition whose universalizing approach exceeds, and indeed attempts to subsume, all of its predecessors. Nothing evokes the Iranian origins of this now global religion more vividly than a visit to the beautiful Persian gardens surrounding Baha'i shrines of Acre and Haifa in Israel.

Why have the extraordinarily broad and profound influences of Iran on the world's religions gone so largely unnoticed for so long? Simple, authoritative answers are elusive, but a few tentative suggestions may be made. The comparative historical study of religions as an academic approach is fairly recent, as well as Western in origin and orientation, resulting in several fundamental biases.

One such bias favors Classical Greek and Roman civilizations as superior models and primary sources of influence on later human societies. Another bias tends to define cultures in terms of key texts and the languages in which they were written, to the detriment of other sources whether textual or otherwise. Comparatively few such texts were originally composed in Persian or other Iranian languages.

The fact that historically, a preponderance of Iranian writers great and small have chosen to write in non-Iranian languages -- whether Aramaic, Arabic, Sanskrit, Chinese, or English -- has led to a situation where even in these enlightened times one still finds major Iranian figures like Avicenna, Ghazali, and Rhazes referred to as "Arab" writers.

The thousand and one stories with which that brilliant Persian raconteuse, Shahrzad (Scheherezade), enthralled a mythical Persian king continue to be known by many as "The Arabian Nights."

Yet it takes but the faintest scratching to uncover the legions of important Iranians and Iranian ideas lurking beneath the literary veneers of world history. The task of this book, therefore, is a relatively easy one, consisting mainly of pointing out what ought to be clearly visible but has, like a finely crafted old table relegated to an over-stuffed storage room, for too long remained out of sight and under-appreciated.

Richard C. Foltz, Québec, QC

24 June 2003 (Fête nationale de St. Jean)

4 Tir 1382

Amazon.com: Spirituality in the Land of the Noble: How Iran Shaped the World's Religions

CONTENTS

“The book comprises nine chapters, plus a useful map and a bibliographic essay that opens enticing avenues for further research. Chapter 1 deals with the origins of Iranian religion, and examines the controversial topic of “Indo-European” migrations across Eurasia. Given Iran’s self-designation as Aryan (literally “noble”, hence the title of the book), this is an important discussion. It rightly warns against collapsing language and ethnicity into each other, as many of the peoples who adopted Persian (Ottoman Turks, Moghul Indians) did not live in the Iranian plateau, and many who live in the Iranian plateau have languages such as Turkish, Kurdish, Arabic, and Armenian as their mother tongue. This chapter also makes interesting comparative points about connections between Iranian and Indian religions.

Chapter 2 considers the long-standing state religion of pre-Islamic Iran, Zoroastrianism. Today reduced to a following of a few hundred thousand in Iran and India, Zoroastrianism was once one of the world’s great religions. More important than its numerical significance today is the impact it has had on other religious traditions. Foltz convincingly demonstrates that many key concepts in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam can be traced to Zoroastrianism. Examples include the linear progression of time towards a great culminating event, posthumous judgement of the individual, and bodily resurrection. Remnants of Zoroastrian practices continue to feature in Persian culture, such as the spring equinoctial feast of Noruz.

In our age, the ongoing Palestinian–Israeli tragedy is the lens through which almost all Jewish‑Middle Eastern interactions are viewed. Most readers will benefit from chapter 3, which traces the long and profoundly important history of Iranian Jewry. Foltz relates how the Persian king Cyrus is described as “anointed” in the book of Isaiah for having liberated the Israelites from their Babylonian captivity. The book of Esther is likewise set in the Iranian context. The tombs of figures such as Mordecai and Daniel have long been centres of Jewish (and Muslim) pilgrimage in Iran. Even more significant for the modern practice of Judaism, the Babylonian Talmud (completed around the year 600 ce) was largely compiled in the Iranian cultural sphere.

Chapter 4 deals with Buddhism. While most traces of Buddhism have long vanished from Iran, Foltz ably demonstrates that cities such as Balkh had over a hundred Buddhist monasteries in the seventh century ce. The Buddhist heritage of Persianate regions came to global attention with the Taliban’s destruction of the Bamiyan statues in Afghanistan in 2001.

Chapter 5 focuses on the Iranian Christian heritage. Iran served as the gateway through which Christianity was introduced to much of Asia: the Chinese referred to Christianity as “the Persian religion”. Initially the target of Zoroastrian polemics, Christians in Iran came to be accepted (or at least tolerated) as a key component of Sassanian Iranian society. As in many other places in the Nile-to-Oxus region, in Iran Christians (along with Jews) came to dominate professions such as medicine, which granted them access to courtly culture and all the power that comes with such access.

Chapter 6 deals with Gnostic traditions in Iran, particularly persecuted traditions such as Mandaeism and Manichaeism. Manichaeism, in many ways the archetypal pre-modern heresy for both Christians and Muslims, has proven profoundly significant by serving as the foil against which other traditions defined themselves. Other oppositional movements such as Mazdakism would follow suit, mixing in an Iranian nationalist element by rejecting Arab rule.

The great story of Iran for the past fourteen hundred years is, of course, Islam, the religion that today defines the allegiance of over 99 per cent of Iranians. It is to Foltz’s credit that Islam does not dominate this book, but occupies only one chapter (7). The focus here is on the plurality of expressions of Islam in Iran, such as Sunnism, Shi’ism, and Sufi mysticism. One of Foltz’s more controversial assertions is that by the classical age of Islam, “Iranians would come to play a larger role” in Islam than Arabs (p. 123). While this reviewer would tend to agree, some readers might desire greater evidence for that claim. Part of its shock-value, of course, derives from the Arab-centred view of Islam that is mainstream and traditional. Foltz does point to a wide array of influential Iranian Muslims, ranging from the philosopher–theologians al Ghazali and Avicenna to the grammarian Sibawayh and the mathematician Khwarazmi. Just as intriguing as individual thinkers and scholars are wholesale institutional pre-Islamic Iranian practices which were carried over into Islamic Abbasid times.

Chapter 8 focuses on the rise of the Babi and the Baha’i faith in Iran. Here we are presented with the complex and highly contested history of an entirely modern religious movement which emerged out of messianic Shi’ism and came to be seen both by its adherents and its antagonists as a new religion. Foltz’s chapter is significant in being one of the first treatments of Baha’ism that is not written by a practising Baha’i.

Chapter 9 offers a summary of the current state of religious minorities in Iran. Three non-Islamic traditions (Christianity, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism) are officially recognised, with another (Baha’ism) acknowledged but not recognised. The official government stance on Baha’ism is that it was a British conspiracy to divide Muslims against one another, and was subsequently supported by Zionism. Foltz ends his book by offering a brief account of the interest of modern Iranians in what we may call comparative religion.”

*The above summary is by Omid Safi, co-chair of the Study of Islam Section at the American Academy of Religion, and editor of Progressive Muslims: On Justice, Gender, and Pluralism (Oneworld, 2003).

Iran, Cradle of Faiths - Centre for World Dialogue

For further reading see:

Revisiting the Persian cosmopolis: The World Order and the Dialogue of Civilisations

The Cyrus Cylinder: Ancient Persia’s Gift to the World

Modern Iran: The Most Misunderstood Country