The world in pain:‘Coronavirus is a warning to us to mend our broken relationship with nature.’+

The Gift of Creation as God’s Love Story

A forgotten love story by Mona Finden

God’s Love Story: Pathways to Healing

The world has never been so fragmented and in pain. This is why, to my mind,

the time is now to rekindle ourselves with God’s Love Story

‘Open our minds and touch our hearts, so we may be attentive to Your gift of creation’

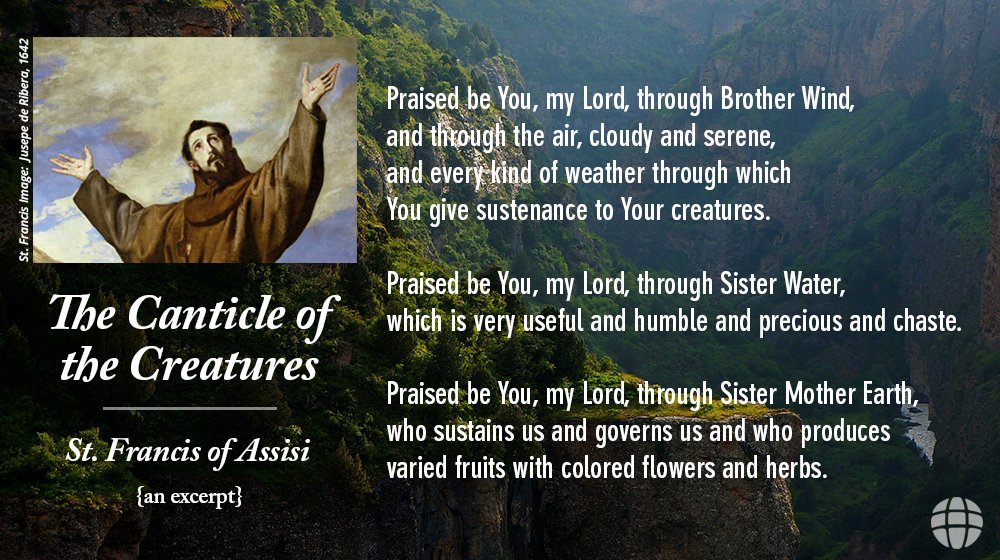

‘The Canticle of the Creatures’, also known as ‘The Canticle of Brother Sun and Sister Moon’

is the first poem written in Italian.

Its author is Francesco d'Assisi who composed it in 1226.

Poetry is a praise to God, to life and to nature that is seen in all its beauty and complexity.-Photo: twitter.com

Nota bene

‘...God first spoke through creation before speaking more definitively in the person of Jesus. The study of the natural world through science, and a faith that seeks to understand who Jesus is and why he matters can converge in dialogue and be complementary in understanding how God is present and acts in our world. The current climate crisis has exposed our inability to sense and percieve the inherent sacredness of the world, in every tiny bit of life and death. We struggle to see God in our own reality, let alone to respect reality, protect it, or love it. The Consequences of this ‘blindness’ are all around us, seen in the way we have exploited and damaged creation and our fellow human beings, particularly the most vulnerable…’- Fr. Krish Mathavan MSC

‘The Creation of Adam, Michelangelo, c. 1512, Sistine Chapel. It illustrates the Biblical creation narrative from the

Book of Genesis in which God gives life to Adam, the first man. The image of the near-touching hands of

God and Adam has become iconic of humanity.’-Photo and quote: Wikipedia

‘Divine Revelation in the Creation Story: Humanity is Made for Love.’

‘FROM first to last, the Bible presents an astonishing and beautiful vision: the world is a good gift from the good and gracious God. The name for this understanding of the world as a gift is creation.

The book of Genesis opens with a magnificent vision of creation, a vision recapitulated and magnified in the closing images of Revelation, when the same God who first created again “makes all things new” (Revelation 21.5).’

Photo: AnswersinGenesis

Creation: an act of love*

‘FROM first to last, the Bible presents an astonishing and beautiful vision: the world is a good gift from the good and gracious God. The name for this understanding of the world as a gift is creation.

The book of Genesis opens with a magnificent vision of creation, a vision recapitulated and magnified in the closing images of Revelation, when the same God who first created again “makes all things new” (Revelation 21.5).

Confession of God as the good, faithful, and loving creator suffuses the texts in between the two books and is an essential part of Christian confession. The world is neither a brute fact, nor a text without a context. God precedes and exceeds the world, but not as something bigger and older: rather as the absolute and infinite source of all. Creation exists because God, from everlasting to everlasting, gives the world to be.

The doctrine of creation is not one disconnected doctrine among many, but a great mystery bound up with the other great mysteries of Christian faith: the Trinity, the incarnation, the mysteries of redemption, and new creation. All of our believing, all of our Christian reflection, all of our praying and serving is tied into the doctrine of creation. Properly understood, the doctrine changes everything. Significantly, within the Abrahamic traditions, the distinction between Creator and creatures is the first, most basic, and most important distinction one can make.

Beyond origins and ecology

The Garden of Eden by Thomas Cole, 1828

TODAY, however, “creation” is a much-diminished term. Both in the Church and in popular culture, creation is often reduced either to a discussion of origins or to a kind of ersatz religious ecology. Both reflect a deeper tendency to reduce the idea of creation to something more or less empirical, treating the doctrine of creation as if it were no more than a teaching about nature.

Consider the reduction to origins. When creation is treated primarily as a doctrine about origins, it is often forced to play a part in the supposed war of religion and science. In truth, the great antagonists in this battle are not, in fact, religion and science per se, or creation and evolution, but rather stranger, more extreme species of each: creationists squaring off against what we might call evolutionists. And the view of creation presupposed in this battle of religious and scientific fundamentalisms is an impoverished one.

Indeed, as Conor Cunningham has shown, not only is nothing in the classical Christian doctrine of creation incompatible with the best of evolutionary theory, but it could even be argued that a Christian vision of creation helps to make the evolutionary sciences themselves intelligible.

Strictly speaking, the doctrine of creation is not about “physical origins”, since when we investigate the origins of a thing, we naturally look for evidence of how it came into being from something. But what is created in the theological sense is not made by this kind of movement or change, since nothing pre-existed the creation (Aquinas, Summa Theologiae).

Before creation, there is simply nothing to be changed; no preceding world to compare with what comes after. Creation is not about external change, and, therefore, not about origins; creation is about relation — the radical, absolute, asymmetrical but loving relation of dependence upon God that shoots through the heart of all things.

APART from the question of origins, perhaps the other most popular way in which people today speak about creation has to do with issues related to the environment and ecology. Environmentalists have argued that Christian teaching about the “dominion of man” in the midst of creation has been ecologically disastrous.

To be sure, human beings have often acted idolatrously, regarding ourselves not as responsible members of the community of God’s creation, but rather as the masters and possessors of nature. As many theologians have pointed out, however, the biblical name for such exploitation and hubris is sin.

Far from licensing the defoliation of the more-than-human world, Christian scripture and tradition present us with a vision of creation as something to which we belong, something that human beings as God’s chief representatives upon the earth are commissioned to care for, to protect, and to nurture.

PROMINENT and important as our current cultural conversations about origins and ecology may be, the doctrine of creation intends to say something vastly more encompassing and profound than either of the above discussions can admit. For creation is not (only) about a beginning in time, nor is it (only) about the relations of creatures one to another; far more basically, it is about all creatures, all times, being and time themselves, issuing from, ordered to, and dependent upon, the God who alone gives all to be.

Triune creator of heaven and earth

Disputation of the Holy Sacrament, Raphael, painted 1509–1510, Apostolic Palace, Vatican City. In the painting,

Raphael has created a scene spanning both heaven and earth.-Photo: Wikipedia

CHRISTIANS largely inherited their belief in creation from Jewish tradition, but they did not leave it unchanged. How could they, since the story of the gospel is the story of how the same God who created the world became incarnate to redeem it?

As Athanasius (AD 296-373) writes:

We will begin, then, with the creation of the world and with God its Maker, for the first fact you must grasp is this: the renewal of creation has been wrought by the Self-same Word who made it in the beginning. There is thus no inconsistency between creation and salvation; for the One Father has employed the same Agent for both works, effecting the salvation of the world through the same Word Who made it at the first. (On the Incarnation).

We are sometimes tempted to think of God the Father as Creator, God the Son as Redeemer, and the Spirit as the Sanctifier, but this is an unfortunate way of speaking. Rather, scripture and tradition alike teach that all of the great acts of creation, redemption, and sanctification are acts of the Father through the Son in the Spirit. It is the one God in three persons who creates.

Why is this Trinitarian vision of creation important? In part, because it prevents us from pitting the goodness of the God who saves against the God who made the world with all of its apparent tragedies, as Marcion and many of the so-called Gnostics were tempted to do.

But confession of the Triune Creator is important for other reasons, too. Aquinas thought that only the doctrine of the Trinity allows us to see how God’s creation of the world could be understood as a free act of divine love. Accordingly, without knowledge of the divine persons, we cannot have a “right idea of creation”.

As Aquinas explains:

When we say that in Him there is a procession of love, we show that God produced creatures not because He needed them, nor because of any other extrinsic reason, but on account of the love of His own goodness. (Summa Theologica)

More recently, others, such as the Protestant theologian Wolfhart Pannenberg, have argued that the unity in distinction of the Trinitarian Person is what allows for the creation of a world distinct from God. The space between the Father and the Son, as it were, provides the condition of possibility for the being of God’s creatures.

Creation out of nothing, creation out of love

ALTHOUGH the doctrine of creation out of nothing (creatio ex nihilo) is not explicitly taught in the scriptures, by the fourth century it had become an essential component of orthodox Christian teaching about creation. Arguably, it was the second-century author Theophilus of Antioch who provided the first formal articulation of creation out of nothing. Theophilus, in turn, was a great influence on subsequent church Fathers, not least Tertullian (AD c.155-c.220) and Irenaeus of Lyons (AD 130–202).

In the hands of the Fathers, creation out of nothing became a way of confessing that everything about everything comes from God: the matter, form, meaning, and end of each and everything owes its existence without remainder to the God who gives it to be.

Thus Irenaeus writes:

While men, indeed, cannot make anything out of nothing, but only out of matter already existing, yet God is in this point pre-eminently superior to men, that He Himself called into being the substance of His creation, when previously it had no existence. (Against Heresies)

Creation out of nothing is perhaps best understood as a doctrine intending to guard a mystery, rather than to unveil one. To say that God creates out of nothing is not to say anything about how God creates, nor does it say anything about what God uses to create. God needs no intermediaries, and uses no tools. There is no pre-existing material, no pre-existing forms or subjects on which God sets to work. God is the sole and exhaustive cause of the creature, both its substance and its intelligibility.

To many in the ancient world, this seemed a preposterous doctrine. How much more rational was Plato in his Timaeus, which pictured God as a demiurge or cosmic architect, imposing form on a kind of material receptacle. Plato’s creating “demiurge” may rightly be said to have made this world, but he cannot be called the creator of the universe itself, nor is he responsible for each and every aspect of the world, insofar as recalcitrant matter may resist the demiurge’s will.

Christians, in contrast, have traditionally insisted that God is the good Creator of all things, visible and invisible. Rather than Plato’s three cosmological ultimates (form, matter, and divinity), the Triune Creator alone is the ultimate fountain and source of being.

CRITICISMS of the ex nihilo doctrine reappeared with vigour throughout the past century. Process philosophers and feminist theologians often led the charge, arguing that creation out of nothing is an extra-biblical doctrine that robs the world of its inherent power, and paints a despotic picture of God.

The consequences of such a vision, they argue, are dire. On the one hand, if the world lacks the power to determine its own being, then God must be the cause and author of everything — horror and beauty alike — and the problem of evil becomes intractable. On the other hand, they insist, the doctrine of creation out of nothing divinises a totalitarian vision of irresistible and unbreakable will. Who would want to worship such a God?

A full response to such charges is beyond the scope of this article, but one can argue that such critics deeply misunderstand the meaning of the ex nihilo doctrine. The classical doctrine of creation out of nothing makes it completely impossible to imagine that Creator and creatures could exist in any sort of competitive relationship.

Because all creatures depend entirely on God for their existence, there can be no question of creatures and Creator jostling one other for room. As Rowan Williams has argued (in his essay “On Being Creatures”), creation cannot be an exercise of God’s power over his creatures because — apart from creation — there is simply nothing over which power might be exercised.

Creation out of nothing is not a doctrine of power, but of love: because creation is ex nihilo, we must also say it is ex amore. Because there are no external constraints on God’s act of creating, everything exists out of the sheer freedom of God’s love.

Things are not as they are because they have to be, but because God first loved them into being, continues to sustain them by this love, and will yet somehow transform them further in love. Not just somehow, in fact, but very particularly, for the God who has the power to call into being things that were not, also has the goodness to call all things to become what they are not yet, catching all into the life of God through the life, death, and resurrection of Christ.

Creation waits and groans with eager longing, as Paul says in Romans 8, while we ourselves groan inwardly, awaiting the redemption of our bodies and the redemption of this world, the new heaven and the new earth brought together finally in the new creation of all things, as they were already brought together in Christ himself.’

* The above article by Dr Jacob Sherman, University Lecturer in Philosophy of Religion at the University of Cambridge, and the author of Partakers of the Divine: Contemplation and the practice of philosophy (Fortress Press, 2014), was first published in Church Times on 19 February 2016

+Coronavirus is a warning to us to mend our broken relationship with nature

The Tapestry of Creation or Girona Tapestry

The Girona Tapestry, needlework (late 11th century, Museum of Girona Cathedral)

‘Read it as you would read a clock face. At nine o’clock, the earth is a void. At eleven, an angel is in darkness. At twelve, the spirit hovers over the waters. At one, there is an angel in light; by three, the sun and moon have appeared, and the waters beneath are separated from the waters above. Then it is Genesis two: Eve is created at seven, Adam names the beasts at four, and the birds and the beasts revel in abundance at six o’clock.

Read it like a clock, but this is not a moment in time. This is a circle and Christ is the fixed point, blessing this creation forever. God is the source and the destination of this creation. There is nothing about dominion here, no hierarchy. The man and the woman are in the midst of it all, and images of what their stewardship might mean surround them.’-The Very Revd Dr David Hoyle

Read more:

God and Creation: Trinity and Creation out of Nothing

Laudato Si: On Care for our Common Home

‘Open our minds and touch our hearts, so we may be attentive to Your gift of creation’

Laudato Si': On Care for Our Common Home is the new appeal from Pope Francis addressed to "every person living on this planet" for an inclusive dialogue about how we are shaping the future of our planet. Pope Francis calls the Church and the world to acknowledge the urgency of our environmental challenges and to join him in embarking on a new path. This encyclical is written with both hope and resolve, looking to our common future with candor and humility.

The title is taken from the first line of the encyclical, "Laudato si', mi Signore," or "Praise be to you, my Lord." In the words of this beautiful canticle, Saint Francis of Assisi reminds us that our common home is like a sister with whom we share our life and a beautiful mother who opens her arms to embrace us. The encyclical is divided into six chapters which together provide a thorough analysis of human life and its three intertwined relationships: with God, with our neighbor, and with the earth: Continue to read and explore more