William Morris, Britain's most inspiring designer: Walthamstow’s Gift to the World

‘Simplicity of life, even the barest, is not a misery, but the very foundation of refinement: a sanded floor and whitewashed walls, and the green trees, and flowery meads, and living waters outside; or a grimy palace amid the smoke with a regiment of housemaids always working to smear the dirt together so that it may be unnoticed; which, think you, is the most refined, the most fit for a gentleman of those two dwellings…?

And then from simplicity of life would rise up the longing for beauty, which cannot yet be dead in men’s souls, and we know that nothing can satisfy that demand but intelligent work rising gradually into imaginative work; which will turn all “operatives” into workmen, into artists, into men.’—William Morris

William Morris: A Man for All Times

The historian EP Thompson characterised Morris as “one of those men whom history will never overtake.”

William Morris, photographed by Frederick Hollyer in 1884. Photograph: © National Portrait Gallery, London

William Morris, born on 24 March 1834 at Elm House, Walthamstow, East London, was a revolutionary force in Victorian Britain: Known for his fantastic floral prints, William Morris designed tapestries, wallpaper, fabrics and furniture during the latter part of the 19th century. He was also a celebrated artist, poet, writer and social activist. His genius was so many-sided and so profound that its full extent has rarely been grasped. Many people may find it hard to believe that the greatest English designer of his time, possibly of all time, could also be internationally renowned as a founder of the socialist movement, and could have been ranked as a poet together with Tennyson and Browning. His designs are still widely used today and so are many of his ideas and principles. Morris has enabled us to dare to imagine and envision a more beautiful world. Throughout his life he laboured through his creative endeavours to beautify the earth and the lives of those who dwell upon it. Long may it be so.

William Morris: A Life for Our Time

A moment that changed me: The day I discovered William Morris

THE ARTS & CRAFT MOVEMENT: The Slow Pursuit of a Slower and Simpler Life

‘All art starts from this simplicity; and the higher the art rises, the greater the simplicity.’

Photo:wikimedia.org

Elm House, Walthamstow; original illustration to Mackail's 'Life of Morris'-Edmund Hort New (1871 - 1931)

Photo: William Morris Gallery

William Morris and His Legacy: The Virtues of Simplicity and Valuing Beauty

Daisy wallpaper, 1862 designed by Morris. Photograph: © William Morris Gallery, London Borough of Waltham Forest

The Beauty of Simplicity — Living a Simpler Life, William Morris’s golden rule for a good and worthwhile life, his words and sentiments resonates with me. Why, you may ask? To answer this question, I need to go back in time, when, over twenty years or so ago, I faced, possibly, the biggest challenge to my way of life. It could have been very disastrous. But now looking back, one consequence of that very sad time, was the fact that ‘Simplicity’, ‘Living Simply’ which was forced on us, has turned out to be the biggest gift we could have ever had.

Let me recall, what I had noted about this awhile back:

Life is so full of unpredictable beauty and strange surprises

As many people, wiser than me have noted, our lives and the world in which we all live, are so unpredictable. Things happen suddenly, unexpectedly. We want to feel we are in control of our own existence. In some ways we are, in some ways we're not ... Life, it can bring you so much joy and yet at the same time cause so much pain.

I was so devastated that after this wonderful journey, full of joy and happiness, achievements and success, due to some reasons beyond my control, I started to feel unwell, unhappy, not enjoying what I was doing and teaching, especially when I lost all confidence in the value of moral-free economics that I was teaching my students, and more.

In 1999 I voluntarily resigned from my post at Coventry University. It goes without saying that, I was heartbroken and extremely hurt that I was unable to nurture and develop further what I had envisioned and built.

Looking back, reflecting on what has happened, I think, somehow, somebody, somewhere, had planned it so that I, too, should have a life, similar to the life of Coventry itself: fall and rise again,...Continue to read

Yes, I left my employment. I lost my income. But, in the process, I discovered more about myself. I rediscovered the love of my wife, my children, family and a few friends that had decided to remain with me. My wife, my children, and myself were pushed into opting a far more simpler life that we had ever imagined before. This has encouraged us to become more aware of who we are, what and why we are and also what the most important and precious in life are. For all these, I cannot be more grateful and thankful.

All in all, for the last couple of decades, we have been living a (relatively) simple life, or to put it another way, we have been living a simpler life, that we may have not been living, if life had not played the card, as it did, all those years ago, as I noted above.

Thus, as the complexity of my life grew, and I renewed my commitments, I chose to lead my life more simply. I could, I suppose, have found solace in artificial lift-ups, drugs and alcohol. I am grateful I did not. I chose love, I chose mother nature, volunteerism, taking action in the interest of the common good. I chose to share and tell my story. I founded the GCGI and in the process found the best, most beautiful friends I could have ever imagined I could have.

Living a simple life is about paring back, so that you have space to breathe. It’s about doing with less, because you realize that having more and doing more doesn’t lead to happiness. It’s about finding joy in the simple things, and being content with solitude, quiet, contemplation and savoring the moment.

Of course, these are not the only gifts you’ll receive for living a simpler life. The best ones are the ones you will discover yourself. Try simpler life and see what happens — I think you’ll find out something beautiful about yourself, and about life.

In short, the best kind of simplicity is that which exposes the raw beauty, joy and heartbreak of life as it is; not the Facebook and Instagram life, but life as it should be: real, authentic, ups and downs, love and being loved. Carpe Diem!

Photo:bmhonline.wordpress.com

‘This golden rule of housekeeping was first uttered by William Morris, a celebrated 19th century designer, entrepreneur and writer in a speech to an assembly of designers in Birmingham in 1880. It wasn’t offered as a styling tip so much as a call to arms in an ideological battle on the course of civilisation.

Morris wanted to inspire people to challenge the norms of a society that in its ‘hurrying blindness’ pursued wealth and economic growth at the expense of what he called ‘the beauty of life’.

Morris grew up in the age of industrialisation, seeing factories spring up in the cities and machine-based methods of production take hold. He regarded the jobs on the assembly lines as dehumanising.

As a young man, Morris engaged an architect friend Philip Webb to design and build him and his new wife a family home, called Red House. Morris used this project as an opportunity to test the idea of a craft-based community, with his circle of friends working together to handcraft almost all the furnishings in the house.

Red House in Upton, Bexley Heath, Greater London. Photo:flickr.com

Through this experience Morris learned firsthand what science took another century to establish, that work if properly designed can be an inherently enjoyable and meaningful activity.

He set up an interiors company with his friends, determined to prove that it was possible for a business to make solid well-designed objects for the middle classes using traditional methods of craftsmanship. The difficulty was that quality goods made by artisans, if paid fairly, would cost more than mass-produced goods made in factories. How would people pay for them?

Morris’s answer: by living a simple life. If people consumed less, they would have more money to spend on solid and durable goods that would not need to be replaced, saving them even more money in the long run.

If you want a golden rule that will fit everybody, this is it:

‘Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.’

And if we apply that rule strictly, we shall … create a demand for real art, as the phrase goes; and in the second place, we shall surely have more money to pay for decent houses.

Morris believed education could change consumer behaviour and in turn drive demand for high quality, ethically made goods. But his message went largely unheeded for more than a century.

It is only now that there is growing consciousness of the need for mindful consumption as we come to terms with the environmental devastation wrought by industry and the exploitation of foreign workers in the supply chains of large corporations.

We can only imagine what Morris would make of the course of civilisation since that day, or how he would view his legacy. Morris & Co. fabrics, wallpapers and homewares are still in production, but they are high-end products out of reach for most middle-class customers.

If we take nothing else from his life and work, we can learn to consume more carefully, appreciate art and beauty – and keep our houses as he commanded.’ Read the original article

William Morris’s Thoughts and Reflection on a Good Economy

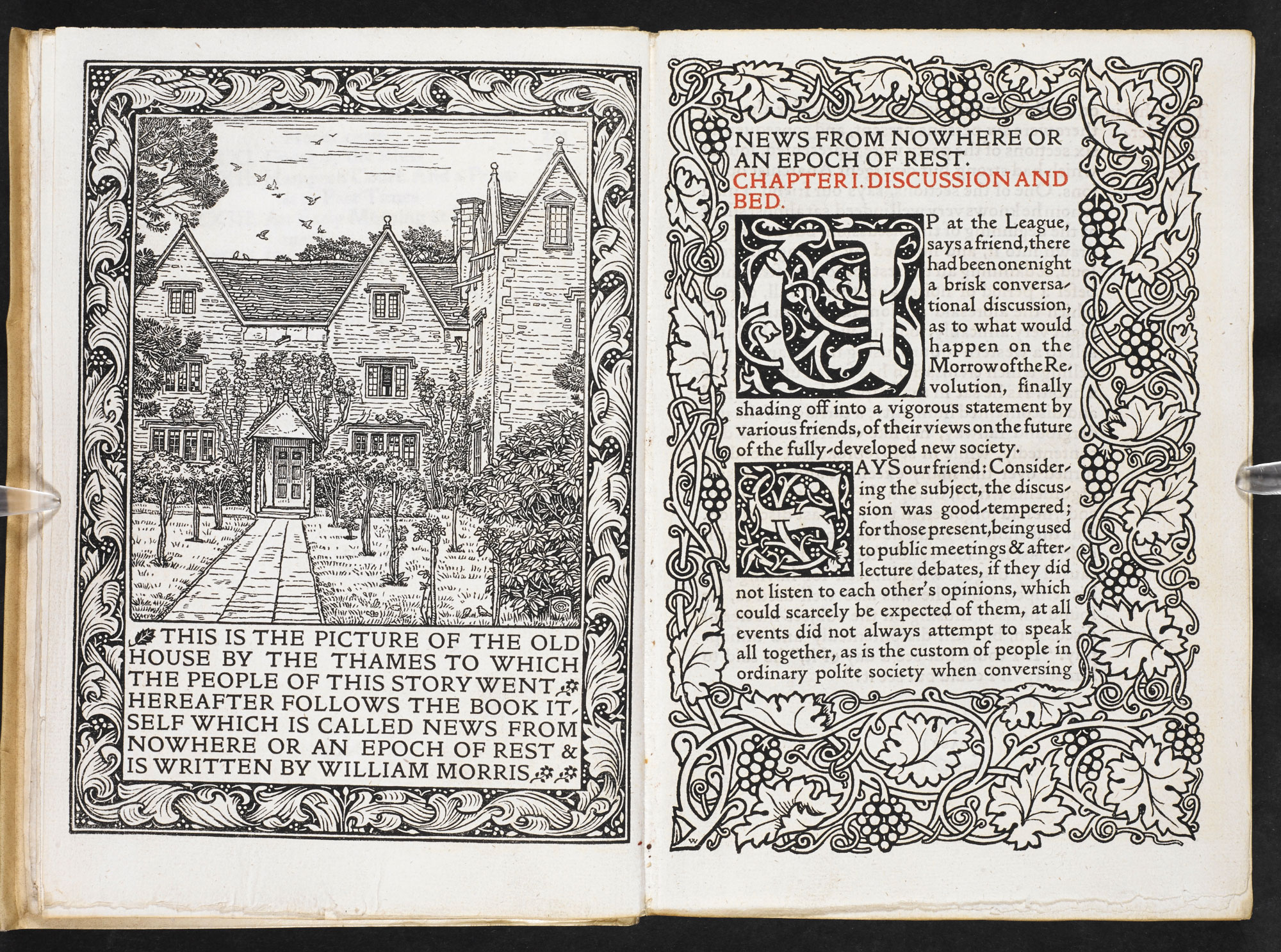

1892 Kelmscott Press edition of News from Nowhere, with a woodcut of Kelmscott Manor,

Morris’s summer house in the Cotswolds. Photo: British Library

In News from Nowhere, Morris imagined a world in which human happiness and economic activity coincided. He reminds us that there needs to be a point to labour beyond making ends meet – and there is. Unalienated labour creates happiness for all – consumer and creator; whereas modern capitalism, in contrast, has created a treadmill in which this aspect of work has been lost. Capitalism, he explains, locks the capitalist into a horrible life, which leads nowhere but the grave.

Morris’s utopian society has no government nor a monetary system. Craftwork has made ‘wage slavery’ obsolete, and parliamentary democracy has given way to new forms of cooperation. The means of production are democratically controlled, and people find pleasure in sharing their interests, goals and resources. The central character and narrator, William Guest, finds himself in conversation with a young girl, a citizen of Morris’s utopian society: Continue to read

Morris directs our attention to a set of centrally important tests that a good economy should pass:

How much do people enjoy working?

Does everyone live within walking distance of woods and meadows?

How healthy is the average diet?

How long are consumer goods expected to last? Are the cities beautiful (generally, not just in a few privileged parts)?

The economy can (with fatal ease) feel as if it is governed by abstract, complex laws concerning discounted cash flows and money supply. His point is that, nevertheless, the economy is intimately tethered to our preferences and choices. And that these are open to transformation. It may not be necessary (as Marx thought) to bring factories and banks and all the corporations into public ownership; and it may not be necessary (as Milton Friedman and others claimed) to wind back government impact on markets. The true task in creating a good economy, Morris shows us, lies much closer to home...Continue to read

Get to know William Morris better

William Morris Gallery-Walthamstow

The Good News: William Morris is becoming fashionable again!

‘Amid the economic rubble, a revolution is being knitted’*

Rebirth of the arts and crafts movement is now, once again, guiding our search for quality of life in a post-consumerist, recession-hit society.

‘...At a moment when laid-off bankers are testifying to the benefits of basket-weaving, a reversion to the reformist aesthetic of John Ruskin and William Morris can feel suitably corrective. The old manifesto has serious contemporary traction: respect for nature, dignity of labour, importance of long-garnered skills, access to beauty for all.

The reasons for this resurgence are not hard to fathom: we are producers frustrated with never seeing the end product of our efforts; consumers weary of being bullied into buying stuff we don't need, that is badly made or doesn't fit; and would-be creators waking up to the fact that inspiration exists beyond the Sunday style supplements.

Plus, craft is a slow pursuit. It takes many evenings to sew a tapestry or knit a jumper. As the author Nick Laird observed about the immediacy of the internet age: "Concentration proves hard to come by in a space where the vaguest thought, whim or wonder can be indulged or resolved in an instant." But you cannot Twitter a cushion cover.

Likewise, while it is a meditation, craft can be a highly social pursuit when our networks feel all too electronic. And for many, thrift is a necessity as much as an ideological position – though anyone who has bought wool or fabric lately will know that the craft economy can be as extortionate as any other.

There is, inevitably, more than a whiff of nostalgia surrounding this renaissance. But bountiful craft is no guarantee of moral purity. As the craft historian Glenn Adamson observes, German National Socialists were particularly enamoured with the patriotic impact and authenticity of craftwork.

As revolutionarily socialist as it strove to be, the arts and crafts movement was riddled with inconsistency. Morris wrestled with the paradox of insisting on art for all while championing creations so labour-intensive they could only be afforded by the few (not to mention the paternalism that dictated the lackadaisical poor could be rescued from the pub by the intervention of cane-weaving).

It's ironic that, as amateur craft surges, the professional sector faces a skills crisis, with courses in such disciplines as ceramics, glass and metalwork closing down. Although the craft industry contributes more to the economy than the visual arts, cultural heritage or literature sectors, and demand for craft skills has never been higher, it remains the Cinderella order of the arts world.

But if craft is, as Richard Sennett argues in his 2008 book The Craftsman, the doing of good work for its own sake, if competence and engagement are the most solid sources of adult self-respect, then the ethic of this industry is as relevant as ever. A recession invites fundamental reassessment of the place of work – and leisure – in our lives. Practically, this means recognising that teaching a tradable, portable skill is one of the best ways to lift people out of poverty. Philosophically, it invites an acceptance that a trade-off between hamster-wheel presenteeism and mollifying consumption has never been good for us and is not feasible in this economic climate.

Crucially, craft is egalitarian. While some in the Labour party appear bent on resuscitating the canard of meritocracy, which divides the gifted few from the unexceptional mass, craft reminds us of the significance of equality of outcome, rather than of opportunity. Everyone shares the capacity to develop a skill, based on decent teaching, application and time – not raw talent.’ *Read the original article

See below for more related articles:

Simpler life and simpler times: A Journey in Life

In these troubled times let us be ordinary and enjoy the simple pleasures of life

The Wonders of an Ordinary Life

In Praise of Frugality: Materialism is a Killer

A beautiful book to read as the nights close in this autumn

A Simple Manifesto for a Simpler Life: Why Simple Life Matters

Photo: lifesanswers.org

‘We live in a time when many people experience their lives as empty and lacking in fulfillment. The decline of religion and the collapse of communism have left but the ideology of the free market whose only message is: consume, and work hard so you can earn money to consume more. Yet even those who do reasonably well in this race for material goods do not find that they are satisfied with their way of life. We now have good scientific evidence for what philosophers have said throughout the ages: once we have enough to satisfy our basic needs, gaining more wealth does not bring us more happiness.’- Peter Singer

Simple Living Promotes Virtue, Which Promotes Happiness

Simple Living is Guided by Economic Prudence, ‘Waste not, Want not.’

Simple Living Allows One to Work in order to Satisfy the Basic Needs and Thus, Enjoy More of life’s Experiences which Suffices for Happiness

Simple Living Promotes Serenity Through Detachment

Living Frugally Prepares One for Tough Times

Simple Living Enhances One’s Capacity for True Pleasures of Life, When Less is More!

Frugality Fosters Self-Sufficiency and Independence

Simple Living Keeps One Close to Nature and the Natural, when one is Guided and Inspired by the Wisest Teacher: The Mother Nature

Simple Living Promotes Good Health and Spiritual Purity

Simple Living Allows us to Speak of Global Responsibility and a Global Community. It Encourages us to Take Action in the Interest of the Common Good.