- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 3878

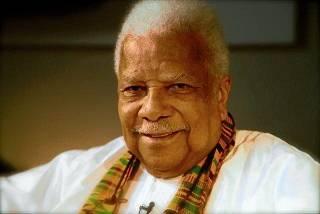

Photo:iol.co.za

Renowned Pan-Africanist, Scholar and Teacher, Ali Al’Amin Mazrui, 81, died peacefully on October 12, 2014 of natural causes at his home in Vestal, New York.

I was blessed and honoured to meet Prof. Mazrui at our Fourth GCGI Annual International conference, which was held in Nairobi and Kericho in 2005. Prof. Mazrui gave the Keynote Address: ‘Can Africa Tame Globalization? Moral Lessons from Cultural Experience’ (see below for the text).

During the Conference I was able to spend some precious moments with him. We were able to talk and debate, both in public and private. I found him endlessly warm, generous, kind and gracious. I value and cherish those moments and memories.

I can only say that Africa and the world have lost a great intellect, teacher and ambassador of peace for the common good. I am praying in my own way for Ali Mazrui. May God grant him eternal rest; he was, in the old idiom, a lovely man, who if required may still be a peacemaker in heaven.

Who was Ali Mazrui? A brief introduction

Ali A. Mazrui was born on February 24, 1933, in Mombasa, Kenya, to Swafia Suleiman Mazrui and Sheikh Al-Amin Mazrui, an eminent Muslim scholar and the Chief Qadi (Islamic judge) of Kenya. Immersed in Swahili culture, Islamic law, and Western education, he grew up speaking Swahili, Arabic and English. He pursued his higher education in the West, obtaining his B.A. from ManchesterUniversity (1960); his M.A. from ColumbiaUniversity in New York (1961); and his doctorate (D.Phil.) from OxfordUniversity (1966).

Mazrui was the head of the Department of Political Science and Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at MakerereUniversity in Kampala, Uganda, until 1973, when he was forced into exile by Idi Amin.

He then taught political science at the University of Michigan, where he was also named Director of the Centre for Afroamerican and African Studies. In 1989, he was appointed as the Albert Schweitzer Professor in the Humanities and the Director of the Institute of Global Cultural Studies at BinghamtonUniversity in New York, a position he held until retirement.

A widely known public intellectual, Mazrui witnessed the ebbs and flows of local and global events affecting Africa and the Muslim world. The anti-colonial revolutionary struggles across the continent provided a compelling backdrop for Mazrui to project the hopes and dreams of millions of people. While pursuing his PhD, Mazrui served as a political analyst for the BBC.

He once served as Vice-President of the International Political Science Association and lectured in five continents. He also was Visiting Scholar at Stanford, Chicago, Colgate, Singapore, Australia, Malaysia, Oxford, Harvard, Bridgewater, Cairo, Leeds, Nairobi, Teheran, Denver, London, Ohio State, Baghdad, McGill, Sussex, Pennsylvania, etc.

In 1986, he became a household name across the English-speaking world by hosting a nine-part television series, "The Africans: A Triple Heritage", which was co-produced by the BBC, PBS, and the Nigerian Television Authority. The series came under attack from right-wing groups that accused it of anti-Western bias, resulting in calls for cutting funding of public broadcasting.

He also served on the Board of Directors of the American Muslim Council, Washington, D.C., and served as chair of the Board of the Centre for the Study of Islam and Democracy, Washington, D.C. He was also on the Board of the Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding, Georgetown University, Washington, D.C., and was a Fellow of the Institute of Governance and Social Research, Jos, Nigeria.

Mazrui was also a gifted teacher and orator. His passion, eloquence, and charisma as a lecturer filled classes throughout his teaching career. Similarly, his reputation for insightful analysis and moving oratory created standing-room only audiences at public speaking events throughout the world. Indeed, his “Millennium Harvard lectures” drew large, engaged audiences for three consecutive days. (The lectures were subsequently published as The African Predicament and the American Experience: A Tale of Two Edens (2004).) Mazrui was, moreover, deeply dedicated to his students. One of the things he regretted most about his declining health was the inability to meet his teaching responsibilities. He was grateful to be able to video-record an apology to his students. He was so adored and revered as a teacher and mentor that family and friends referred to him as “Mwalimu” (Swahili for teacher).

Those close to Mazrui loved him for his character and personal qualities. His warmth was enveloping and his laughter was infectious. He was endlessly generous toward family, close and extended, and to people in less fortunate circumstances. He was gracious to all, including strangers and intellectual adversaries. The hospitality of Mazrui and his beloved wife, Pauline, drew hundreds of visitors to their Vestal, New York home from across town and the world. He also kept in touch with relatives, friends and colleagues in far off places with a personal newsletter that he wrote annually for nearly forty years. He enjoyed learning from people from all walks of life and cultures. An egalitarian and humanitarian, he endeavoured to treat all people with respect, dignity and fairness. At the same time, he valued spirited debate about political, economic and philosophical ideas. Mazrui modelled integrity and decency.

His Research Interests included: African politics; international relations; comparative politics and political theory.

And now I very much wish to share with you the text of his speech at our GCGI Kenya Conference.

‘Can Africa Tame Globalization? Moral Lessons from Cultural Experience’

Prof. Ali A. Mazrui

Keynote Address

“Africa and Globalisation for the Common Good: The Quest for Justice and Peace”

Nishkam St. Puran Institute and Guru Nanak Nishkam Sewak Jatha Complex, Kericho, Kenya, April 18-28-2005

Africa in the twenty first century is likely to be one of the final battlegrounds of the forces of globalization – for better or for worse. This phenomenon called GLOBALIZATION has its winners and losers. In the initial phases, Africa has been among the losers as it has been increasingly marginalized. There are universities in the United States which have more computers than the computers available in an African country of twenty million people. This has been the great digital divide. The distinction between the Haves and Have-nots has now coincided with the distinction between Digitized and the “Digi-prived”.

Let us begin with the challenge of a definition. What is globalization? It consists of processes that lead toward global interdependence and the increasing rapidity of exchange across vast distances. The word globalization is itself quite new, but the actual processes toward global interdependence and exchange started centuries ago.

Five forces have been major engines of globalization across time: religion, technology, warfare, economy, and empire. These have not necessarily acted separately, but often have reinforced each other. For example, the globalization of Christianity started with the conversion of Emperor Constantine I of Rome in 313. The religious conversion of an emperor started the process under which Christianity became the dominant religion not only of Europe but also of many other societies later ruled or settled by Europeans. The globalization of Islam began not with converting a ready-made empire, but with building an empire almost from scratch. The Umayyads and Abbasids put together bits of other people’s empires (e.g., former Byzantine Egypt and former Zoroastrian Persia) and created a whole new civilization. The forces of Christianity and Islam sometimes clashed. In Africa the two religions have competed for the soul of a continent.

In Africa today both Christianity and Islam have over 300 million followers each. There are more Muslims in Nigeria than there are in any Arab country – including Egypt.

In North Africa Christianity arrived in the first century C.E. In Black Africa it arrived in the fourth century – earlier than in many parts of Europe.

Islam arrived in Ethiopia before it arrived in Egypt or Syria or Iraq or Iran. It arrived in Ethiopia with Muslim refugees on the run from anti-Muslim Arabs in the Peninsula. The Prophet Muhammad was still trying to preach in pre-Islamic Mecca.

Today Africa is so much part of the Muslim world that it has sometimes chaired the 50 member Organization of the Islamic Conference. Today Africa is so much part of the Christian world that when Pope John Paul II died there was open speculation as to whether the next Pope, or the next Pope but one, would be an African. This would be the miracle of having a Black African at the top of one billion Roman Catholics in the world. Cardinal Francis Arinzi of Nigeria did not become Pope in 2005. But some other African Catholic may make it before the 21st century comes to an end.

The second and third major engines of globalization are technology and the economy, often in alliance. In recent decades globalization has been envisaged in three different ways:

I. Forces transforming the global market and creating new economic interdependencies. This is economic globalization. Africa is caught up in these forces, for better or for worse.

II. Forces which have exploded into the information superhighway – expanding access to data and mobilizing the computer and the internet into global service. This is the informational side of globalization.

Africa is way behind in this informational globalization. My two universities in the U.S.A. (State University of New York and Cornell) may have more computers than my country, Kenya, with a population of over 30 million people.

In addition to economic and informational globalization, there is comprehensive globalization. The comprehensive scale consists of the following:

III. All forces which are turning the world into a global village compressing distance, homogenizing culture, accelerating mobility, and reducing the relevance of political borders. Under this comprehensive definition, globalization is the gradual villagization of the world. These forces have been at work in Africa long before the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

One of these comprehensive globalizing forces is warfare itself. The twentieth century was the only century which had world wars - 1914 to 1918, and 1939 to 1945. This was the only century which created world diplomatic institutions - the League of Nations and the United Nations. World War II helped Africa’s decolonization by weakening the European imperial powers.

This was also the only century which created a World Bank - the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) with the International Development Association. The twentieth century also issued a Universal Declaration of Human Rights - adopted by the United Nations in 1948. Globalization was getting institutionalized. This was the only century which established a global university - the United Nations University in Tokyo, Japan. Some of these have affected Africa more deeply than others.

This was also the only century which had a world health institution - the World Health Organization (WHO). The twentieth century also created a global mechanism to moderate trade relations - the World Trade Organization (WTO). The Seattle meeting of WTO at the end of the millennium illustrated the depth of feelings about the organization.

This was the only century which had a part-time global policeman - the United States of America. And, of course, this was the only century which developed a genuine world economy - or at least a close approximation to it.

But this conference is not merely about globalization. It is about globalization for the common good in the context of the African condition. And where does religion fit into this equation?

I see Africa’s religious experience as a product of three religious traditions – indigenous, Islamic and Western. If I have any criticism of the agenda of this Kericho conference, it is the apparent neglect of Africa’s indigenous religions as an explicit item in the global agenda.

Nor is this omission unique to this Kericho conference. Neglecting African indigenous religions is a sin committed by many conferences organized by African intellectuals themselves.

In my own humble attempt to correct this omission, I have characterized Africa’s religious experience as a Triple Heritage. I have not only written a book entitled The Africans: A Triple Heritage. I have also done a nine-part television series of the same title for the British Broadcasting Corporation and the Public Broadcasting Service, in association with the Nigerian Television Authority (1986).

But in this presentation today I am addressing not only how Africa has been affected by globalization, but in what ways globalization should learn from Africa if globalization is to be for the common good.

What are the positive elements in Africa’s triple heritage which should inform globalization if it is to be for the good?

Globalization and Ecumenical Africa

Each of the three African legacies – indigenous, Islamic and Western – has something to teach globalization. When indigenous African culture join hands with Islam, it can produce a level of ecumenical tolerance unequalled anywhere else in the world. One of the most striking examples is Senegal in West Africa. The population of Senegal is 94% Muslim – a higher percentage than the Muslim population of Egypt. And yet this overwhelmingly Muslim West African society had a Roman Catholic President -- not briefly as a happy accident but for 20 years without cries in the streets of Dakar demanding “Jihad fi sabili’Llah”! President Leopold Senghor maintained a relatively transparent Senegal. His critics denounced him as a lackey of the French, a cultural hypocrite and worse. But they almost never denounced him as infidel (kaffir).

Senghor was succeeded as President by Diouf, who was indeed a Muslim. But Diouf’s First Lady was a Roman Catholic. Imagine a Presidential candidate in the United States suddenly confessing on Larry King Live that his wife is a Shia Muslim! His candidacy is likely to collapse.

Indeed, the U.S. has been a secular state for two hundred years – and yet the United States has only once strayed from the Protestant fraternity. The Jews have never captured the White House, although they have captured almost every other arena of American excellence outside the sporting experience.

African indigenous culture in Senegal has reinforced Islam in the direction of greater political ecumenicalism. I say “reinforced” because Islam has an independent record of allowing non-Muslims to rise high in status or power.

Boutros Boutros-Ghali would never have become Secretary-General of the United Nations had Egypt not permitted him to rise as high as Minister of State for Foreign Affairs. Boutros-Ghali was a Coptic Christian married to a Jew.

Even Saddam Hussein was ecumenical enough to let Tariq Aziz, a Christian, rise to become Foreign Minister, and then Deputy Prime Minister. No Christian country in the Western world has ever permitted a Muslim to rise to a comparable political rank. The percentage of Christians in Iraq is no greater than of Muslims in France or Britain. Perhaps globalization should learn and improve upon the ecumenical spirit of Senegal and of political Islam.

When African culture interacts with Christianity, it helps produce Africa’s short memory of hate. Cultures differ in degrees of hate-retention. For example, Armenians have a long memory of grievance. The Armenian massacres perpetrated by the Ottoman Empire from 1915 to 1917 have been so vividly remembered by generations of Armenians that Turkish diplomats have been assassinated long after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

The Irish have retained a basic resentment of the English again generation after generation. The Jews have a profound distrust of the Germans more than half a century after the Nazi Holocaust. A Jewish sense of having been violated by the Nazis may last for hundreds of years.

But African culture combined with a Christian background has produced Nelson Mandela who lost 27 of the best years of his life – and emerged ready to have afternoon tea with the racists who had stolen his youth. Post-apartheid South Africa is a remarkable illustration of a short memory of hate – a lesson for the forces of globalization. South Africans have won four Nobel Prizes for Peace.

Jomo Kenyatta was condemned by the British as a “leader unto darkness and death” and was imprisoned in a desolate part of Kenya. He emerged from jail and turned Kenya’s diplomatic orientation in the direction of friendship with Britain and the Western world. He even published a book about what he called Suffering Without Bitterness. Here is another lesson for globalization if it is to become for the common good.

When Africans are fighting each other, they can be as ferocious and unremitting as any combatants anywhere else in the world. The real difference is what happens after the peace accords have been signed. African culture, especially when reinforced by a Christian spirit, has repeatedly demonstrated a short memory of hate.

After their brutal civil war of 1967 to 1970, Nigerians were expected to be cruelly triumphalist against the losers in Igboland. Rivers of blood were expected in the wake of Biafra’s defeat. But the Nigerian leader, General Yakubu Gowon, who led the Federal side, managed to combine Christian compassion with Africa’s own short memory of hate. There were no reprisals against the losers; there were no triumphalist trials like Nuremberg.

The Gender of Globalization

On the issue of gender, the story is more complicated within the three strands of the Triple Heritage. All the three Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam) have been slow in accepting women as equals in church leadership. All the fifteen Cardinals who elected the new Pope Benedict XVI in April 2005 were, of course, men. Nor is it conceivable that there will be a female Pope for at least two centuries, if not longer. The whole vocabulary and nomenclature of Pope, Papa, Papacy would have to change. The vocabulary of the Papacy is largely patriarchal.

The Church of England has at last resigned itself to the ordination of women – but a female Archbishop of Canterbury is unlikely to inhabit LambethPalace in the foreseeable future.

In Christian doctrine as a whole, the Trinity consists of two males and one neuter – the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost.

In both Christianity and Islam it is almost a sin to characterize the Almighty as a “Queen” instead of “King of Kings”. Islam had caliphs [khulafaa] from the seventh century of our common era to the 1923-24 abolition of the Caliphate under Mustapha Kemal Ataturk. Not a single Caliph from 1632 to 1923-24 was a woman.

This tradition of male religious leadership in Islam is now being challenged by the Black world. Especially noteworthy is an activist from the African Diaspora, Sister Amina Wadud from the United States.

In the 1990s she tried to give the Friday sermon at a mosque in South Africa. Liberal Muslims in South Africa were on her side. After all, she was highly educated in Islamic studies, with a Ph.D. from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a book already published entitled The Qur’an and Woman. But the Muslim conservatives in Cape Town were against her being admitted to the mosque at all. In the end a compromise was reached – Professor Amina Wadud gave a pre-sermon sermon at the mosque in Cape Town.

In March 2005 Amina Wadud took the challenge further. She wanted to set a precedent not only of a Friday sermon by a woman, but a woman Imam leading a gender-mixed congregation, shoulder to shoulder. No mosque in New York City would let her violate those historically sanctioned male traditions.

In the end, she led the Friday prayers in a Protestant church in New York – with a gender-mixed congregation and a Friday sermon by herself. Of course, they faced Mecca (the Qibla) in the church, rather than the altar and the cross.

Does Sister Amina Wadud embody globalization for the good? Does she also manifest the old indigenous African traditions of female religious leadership? In this domain of gender in religion, Africa’s indigenous traditions have empowered women centuries before Christianity started debating the ordination of women or Sister Amina Wadud attempted to shake the principles of the Imamate.

Africa has had female warrior priests right into our own era. President Yoweri Museveni had to fight Alice Lakwena in Uganda – a warrior priestess leading an army of tough male Acholis in the 1990s. The Acholi had been regarded by both the British and the first postcolonial governments in Uganda as a “martial tribe”. Yet Acholi macho warriors were ready to follow a woman religio-martial leader into battle against Museveni.

In Zambia in the 1960s President Kenneth Kaunda had to fight another sacred Alice – Alice Lakwena of the LumpaChurch. Tough Zambian males followed a woman priestess in challenging a postcolonial African government. African traditional practices were far ahead of mainstream Abrahamic religions in recognizing women as religious leaders.

While indigenous African culture leads the way in empowering women as religious leaders, Islam has been struggling to accept women as political leaders. A particularly interesting phenomenon is what might be called female succession to male martyrdom. This is a situation in which a woman relative rises to political power upon the martyrdom or death of a male hero.

It started with the Prophet Muhammad’s favorite wife – Ayesha. The Prophet Muhammad himself died a natural death, but three out of four immediate political successors [Caliphs] were assassinated.

In the middle of the tensions of this early Islam, Ayesha rose as a political arbiter and a wheeler and dealer. She almost became a warrior priestess when she participated as a combatant in the Battle of the Camel. She was trying to be a king-maker rather than a queen herself.

The principle of female succession to male martyrdom reemerged in Asian Islam in the twentieth century. Benazir Bhutto became Prime Minister of Pakistan, partly under the credentials of her martyred father, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who was executed in 1979.

In Bangladesh Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was assassinated in 1975. Eventually one of his surviving daughters became the leader of the Awami League and rose to be Prime Minister. Also in Bangladesh, President Ziaur Haq was killed in May 1981. Ten years later his widow became Prime Minister. Since then Sheikh Hasina Wajed and Begum Khaleda Zia have alternated in political power for a couple of decades. The Ayesha tradition of female succession to male heroism has reasserted itself in South Asia.

In South-East Asia the largest Muslim country in population had a female President in this new millennium. Megawati Sukarno Putri, daughter of Founder-President Sukarno, rose to supreme power in Indonesia long after her Dad’s martyrdom. She left office in 2004.

All these Muslim women were heads of government or state long before the United States has had a female President, or France had a woman President, or Italy a female Prime Minister, or Germany a woman Chancellor or Russia a female President.

On the other hand, the Ayesha tradition has not triumphed in Africa either. The assassination of Anwar Sadat did not result in his wife rising to political supremacy. Neither did female relatives of Murtala Muhammad rise to power in Nigeria after he was assassinated in 1976.

Diversity as a Global Ethic

One of the most memorable verses of the Qur’an, the Muslim Holy Book, is a celebration of human diversity. Through the Qur’an God addresses the human species as a whole. He says:

O humankind! We have created you from a single pair of male and female, And made you into Nations and tribes, that you may know each other [respectfully]. Verily the most honoured among you in the sight of God is the most righteous among you. God is the most knowledgeable, the best informed.

[Sura Hujurat, 49 verse 13]

Yaa ayuha Nasu! Innaa khalaqnakum min dhakarin wa unthaa wa jaalnaa kum shu’uban wa qabaila li-taarafu. Inna akramakum i’nda ‘llahi atqaakum. Inna ‘Allaha alimun khabir.

At the core of this Qur’anic verse is a celebration of human differentiation.

We have created you from a male and female and made you into nations and tribes that you may know each other.

[Qur’an: Chapter 49, Verse 13]

Note the plurality of “nations and tribes” and the singularity of purpose – that “you may get to know each other.” The idea is for human beings to seek to know each other across tribal and national divides. What about across the religious divide?

The Qur’an is explicit on that also. It says emphatically that coercion and confession do not go together. The Qur’an says, “There is no compulsion in religion” [Laa ikrahu fi’din]. The God of diversity approves of diversity of the religious experience also.

We created…you nations and tribes that you may know one another.

But as the population of the human race grew and grew, it seemed unlikely that people would get to know each other as God planned. This is when history set in motion the process of human amalgamation. The number of individuals continued to grow almost endlessly (population growth)…but over time the number of tribes and nations decreased. Through conquest, spread of languages, expansion of religions, and empire-building, human clans amalgamated into larger tribes, and small societies merged with bigger nations.

The history of human kind is, on the whole, a history of changing boundaries and expanding societal scale.

He had created us...nations and tribes that we may know each other.

Then God created America and permitted the United States to become the first universal nation in history. No country on earth encompasses as many races, religious faiths, national and tribal origins, as the United States of America does.

Within its own boundaries, the United States has been a human laboratory. It has been experimenting with God’s imperative of diversity – “we have created you…nations and tribes that you may know each other.”

Today the population of the United States is descended from a thousand tribes and many dozens of nations. Within its own borders the United States has begun to facilitate God’s imperative of diversity. Progress in America’s political and social history has consisted of two steps forward, one step backward, advance and retreat. But the total American balance-sheet is a record of human achievement, however imperfect and sometimes painful.

In 2004 the United States celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court decision, Brown versus the Board of Education which came down way back in May 1954. The decision struck down any constitutional basis of racial segregation. It was a major step forward towards rapid integration in God’s laboratory of diversity.

The United States is indeed a democracy at home, but is now also an empire abroad. As a democracy at home, the United States has done more than any other nation in history to create a political system increasingly respectful of racial, ethnic and religious diversity. “We have created you…nations and tribes that you may ‘know each other.”

But abroad the United States and Israel in recent years have generated more rage, hate and hostility than almost any other country in the last fifty years. Within America the United States is fulfilling God’s purpose of promoting the ideal of creative diversity. In its actions abroad, the United States is making it harder for nations and tribes to love each other. The African Diaspora has gained from America as a democracy – two Black Secretaries of State consecutively (Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice). Africa is beginning to suffer from America as Empire. Even earlier than that the U.S. Supreme Court has had two successive Black Justices – Thurgood Marshall and Clarence Thomas. These great African Americans have differed greatly in values, but they were all descended from enslaved Africans.

If the United States wants to be the ultimate architect of democratic diversity, it should focus less on exporting democracy abroad and more on making its own democracy in America work better. Upward political mobility for disadvantaged groups is an aspect of democratization.

The United States is more pluralistic demographically than any other in the world, but that does not mean it is adequately pluralistic democratically. The population demographically consists of almost every group in the world; but the political system does not democratically represent those groups equitably.

Why is it so rare to have a Black person elected to the Senate of the United States? Why have we never had a woman of any race for Vice President, let alone President? How many Muslim Ambassadors are there representing the United States abroad? On the other hand, a Kenyan American – Barrack Obama of Illinois – has become only the fifth Black Senator of the United States for over 200 years.

Africa’s sons and daughters are beginning to influence new trends of globalization. And Africa’s three legacies of the indigenous, the Islamic and Christian may have further lessons to help globalization respond to the common good.

“O human kind! We have created you from a single pair of made and female,

And made you into Nations and tribes that you may know each other.

Verily in the eyes of God the best among you are the most virtuous and righteous.”

Inna Akramakun Inda Llah atqaakum.

Listen, Globalization!

Listen and learn, Globalization.

2005 Kenya Conference Programme

For the list of selected papers presented at GCGI Kenya Conference 2005 see:

GCGI Journal | Globalisation for the Common Good Initiative Journal

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 6147

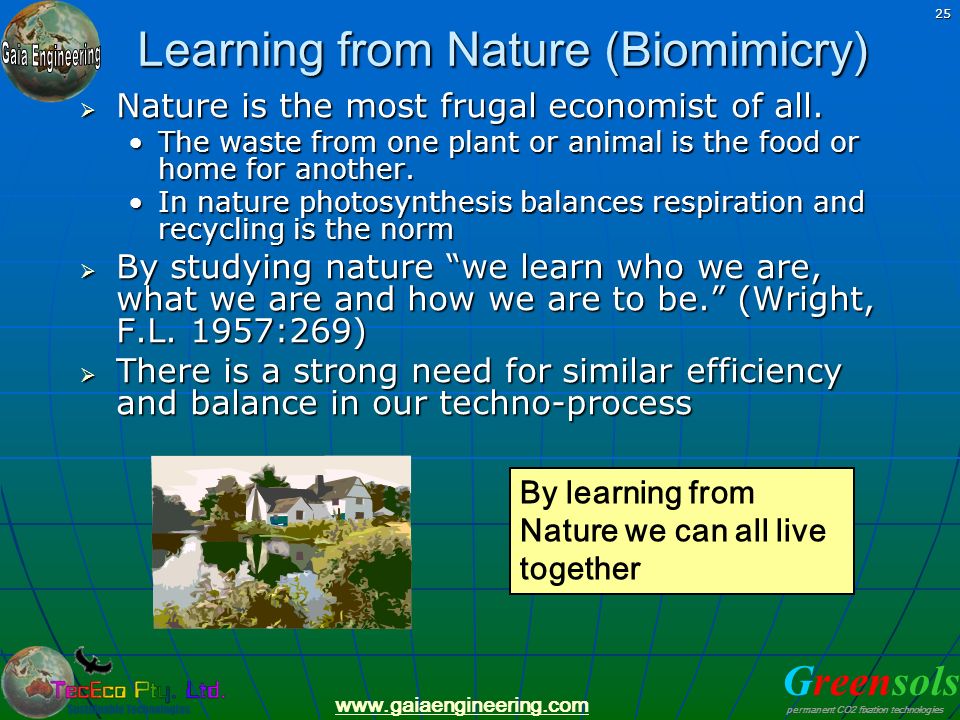

Biomimicry: Observing and Learning from Nature’s Genius

Biomimicry: Observing and Learning from Nature’s Genius

'Biomimicry is studying a leaf to invent a better solar cell, or a bird beak

that inspires an efficient fast-speed train.-Photo and caption:The DailyCourier

“The future will belong to nature-smart—those individuals, families, businesses, and political leaders who develop a deeper understanding of the transformative power of the natural world and who balance the virtual with the real. The more high-tech we become, the more nature we need.” —RICHARD LOUV

Learning from Nature

“For over a decade, we've been living in a society bloated by its own success and excess, congratulating each other on how successful everything has been. Property prices were going to climb for ever, debt was treated as cash for free and technology was going to sort all of our problems. The problem is that we have been ignoring the costs that been paid for a shallow success that's only been measured in financial and material terms. Never has the opportunity for change been as great as it is now as the political, financial, social and environmental needs for common sense outcomes converge towards a single point.”

And now this is where the Wise Mother Nature steps in. Let us take her caring hand and be inspired by her ways.

Photo: thenatureofbusinessdotorg

Engaging with Nature to unlock our creative potential

In times of rapid change we can look to nature for solutions and guidance. Nature has been adaptive and innovative for over 3.5bn years so it knows how to deal with rapid shifts and solve problems. How does nature do risk for example? Or how does nature do communication; Innovation; Leadership and governance? How does nature do marketing; Waste management; Resilience to change, or how nature would optimise outcomes with limited resources, and much more?

As it has so correctly been observed*, the world's ecological, social and economic crises are as much a crisis of spirit as a crisis of resources. Part of the crisis of spirit is because modern society and industry tends to perceive the Earth as a set of resources, and then values it as such. What scope is there for this paradigm to change in order to perceive the Earth as an animate, living system in which humans play a constructive, not destructive, part?

Thus, in order to live differently, to lead a better life, we must search for a better path and begin to think differently. This relates to the way that we see ourselves in the world.

Just as our need to transform business is now becoming apparent, so is our need to transform our engagement with, and response to, nature. Understanding our relationship with nature can help business to transform, and the patterns and principles of nature can provide insight into how best to future-proof companies for an unpredictable future.

All organisations operate within a community – an environment of interconnections – as do the people within organisations. The age-old adage "No man is an island" is the same for an organisation. In fact, just like an ecosystem in nature, the more diverse the relationships and resources an organisation makes use of, the more resilient it becomes.

In building a bridge between nature and business, we start to re-ignite our vital bond with nature.

What do organisations of the future look like?

Collaborative, innovative, networking, emergent, dynamic organisations more akin to living organisms. There are a plethora of nature's insights that can be applied to business – all that is lacking is the ability to convert these insights into a business frame. For example:

• Mycelium networks provide insight for a responsive and adaptive organisation.

• Nature (and business) is emergent and interconnected, not predictable and linear.

• Nature does not do waste; waste of one is food for another.

• Natural ecosystems develop niches where every aspect of the material throughput is used.

A business inspired by nature is one that is resilient, optimising, adaptive, systems-based, values-led, and life supporting – these are "nature's business principles".

These principles do not seek to reduce organisational behaviour to biology; rather, they suggest a set of behaviours and qualities that simply echo the law of the system – Earth – upon which our lives and our businesses depend. They recognise the complexity of human nature and nurture, and are neither a model nor a theory, but rather a philosophy that reminds us that, while humans are a special species on Earth, we are still part of nature and subject to its law. If we do not conduct our business within the constraints of the system, we will inevitably go out of business. The circular economy, industrial ecology, cradle-to-cradle, the learning organisation and bio-mimicry all share a common foundation: they take inspiration from nature.

What is desperately lacking in today's framing of sustainable business, and for that matter wider business transformation, is a language and engagement approach for business people to unlock nature's wisdom and, in so doing, re-enchant ourselves with nature – re-establishing our vital bond with our environment.

By framing experiences people have with nature and giving examples of business inspired by nature, we can reconnect business and nature. To do this, skills and expertise from multi-disciplines are needed: biology, eco-psychology and business change, for instance. This fusion of skillsets, with the right vision and mission, can help equip local, national and global business people with the wherewithal they need to adapt, innovate, embrace change and engage in meaningful business transformation towards a sustainable future.

OK. So far so good. But pertinent questions now surely must be: How should businesses look to nature for inspiration to ensure survival in today’s volatile times, to be sustainable, efficient and profitable? How can they journey toward strategic renewal by implementing ‘natural business strategies’ into their business models?

As it is been commented**, we must make no mistake: The transformation from a firm of the past to a firm of the future is challenging, especially while operating amid of a perfect storm of social, economic and environmental volatility. Successful transformation requires courage, not fear. The more we understand and explore our own business environments and wider business ecosystems (as well as our own inner motives and values) the more we find pathways for success – learning through doing, growth through experience, success through failure. Looking around us in nature and human nature, we find enablers to assist us; catalysts which aid and optimise the transformational journey. Four primary catalysts for transformation are: collaboration, innovation, education and inspiration. Let's explore each in turn:

Collaboration

There has been much written recently about collaboration and co-operation. In fact, this coming decade has been referred to as the decade of co-operation, a time when business executives recognise the power of collaboration and co-operation over competition. It is a myth that nature has evolved over millions of years of combat and competitive struggle; more its evolution is down to networking and partnerships.

Of course there has been, and always will be competition in life, yet evolution benefits far more from collaboration than it does from competition. So does our business environment. We are witnessing a shift in mentality and behaviour from the past approach of "dog eat dog" competition between businesses, business units, and employees to the future approach of collaboration across multi-functional teams, departments, organisations and business ecosystems: interconnectedness rather than separateness, collaboration rather than competition.

Collaboration encourages the transcending of traditional boundaries used to atomise and separate teams, departments, business units and organisations; it interconnects artificial separations in business, encouraging sharing, creativity, empowerment and innovation.

The more we recognise the interconnectedness of the business environment – viewing it as a web of interdependent relationships within interconnected business ecosystems – the more we realise that collaboration (not competition) is key to our resilience and survival in these volatile times. In nature, which has been dealing with dynamic change for over 3.8bn years, we find it is the species that collaborate and interconnect more with their respective ecosystems that are more resilient to changes in their environment; the ecosystem they live in becomes more resilient the more interconnected the stakeholders are within that ecosystem. Ditto for business.

"Cooperation is the architect of creativity throughout evolution, from cells to multi-cellular creatures to anthills to villages to cities. Without cooperation there can be neither construction nor complexity in evolution."

Innovation

Increased market volatility brings with it the need to create, develop and adapt new products and services under time-pressured conditions. In short, innovation is a critical success factor for the future – organisations able to innovate effectively, time and again shall win out over organisations that struggle to adapt. Innovation is fundamental to evolution in all walks of life, not just in business, but for all living species. The good news is human nature is opportunistic and curious by nature; it is in our genes to seek out new and better ways of operating.

The firm of the future creates the conditions conducive for creativity by building a culture that facilitates, empowers, unlocks and supports people's creative potential; an organisation that encourages people to overcome fears and inhibitions, where the work dynamic is of constant evolution, where failure is not criticised but embraced for what it is – an opportunity to learn, adapt and evolve.

Of course, collaboration greatly helps innovation by sharing the burden across a wider group of stakeholders. In nature, organisms evolve best within diverse groups of interconnected specie and likewise, in business an organisation's ability to innovate improves with collaboration amongst a diverse stakeholder group. While economies of scale may bring the benefits of lower unit cost of production, economies of scope bring benefits of increased synergies through greater connections, hence improved innovation. Balancing the benefits of economies of scale with the benefits of economies of scope is crucial for the survival of the firm of the future.

Education

Embracing new approaches to ways of operating is facilitated through an understanding and trust in what, why and how change affects the stakeholders and their respective communities. Ensuring all stakeholder communities are engaged, aware and educated in this transformational journey will greatly optimise the transformative process. A deeper understanding and a greater sense of belonging is needed, rather than just being aware of the upcoming changes we need to empathise with what it means, why it is happening and how it affects the ecosystem of stakeholders involved.

This deeper understanding not only helps the transformation within the department or wider organisation, but also across the interconnected network of stakeholders which the organisation is part of – its business ecosystem.

By educating individuals to a level where there is a true understanding of the values and direction of the transformational journey, these individuals become proponents for change. They are able to educate the other stakeholders they interact with as part of their daily business. The understanding of the transformation, the why and how of it, becomes viral if it is grounded in trust and truth. Hence, the values of the organisation need to deeply resonate with the stakeholders, to strike a chord of belief beyond the goal of short term profit maximisation.

Keeping stakeholders in the dark or only partially aware will only come back to haunt and in turn water down the effectiveness of the transformational journey. This does not mean to say that complete clarity of where the organisation shall be in one or two years time from now is needed, it is more that people truly understand the reasons for change, the drivers for transformation and the value-set of the organisation.

The transformation is more about the journey than the destination, with plots on the course helping to steer a path through choppy water, whilst remaining open and flexible to changes in wind, swells and tide. A firm of the future has a culture that is rooted in values, where leadership is values-based and where the awareness of right and wrong behaviour is second nature. Organisations that encourage the right mentality, by living and breathing their values, ensure that openness, awareness, acceptance and motivation for transformation follow.

Inspiration

We are entering uncharted waters. We are on the cusp of major transformative change, socially, economically and environmentally. Few business leaders have witnessed volatility of the likes we are now faced with. It is as if we are walking in a dark forest at night with only candle light to illuminate a path ahead of us. The candle light allows for vision which brings comfort that our steps ahead are not too perilous, keeping us moving forward even if we are weary and fearful.

Inspiration can come from any and all of us – whether it a visionary CEO committing to zero-emissions by 2020, a new sustainable product line exceeding revenue expectations, a neighbouring plant successfully implementing new sustainable technologies, or a colleague taking time out from a pressing schedule to brainstorm with another in a time of need.

We do not have to be inspired by visionaries or great leaders. In these transformational times, we need to inspire ourselves and the ones around us by simply walking-the-talk and being true to the values of the organisations and communities we serve. The more we look for examples of inspiration within our own business ecosystems, the more we find, and in turn the more we inspire ourselves to be the change we want to see.

The above excerpts are taken from the two original articles below:

Read more:

Biomimicry: Learning from Nature

BBC News - Viewpoint: How would nature tackle the cutbacks

'Superorganisations’ – Learning from Nature’s Networks | The Nature of Business

And now a heart-felt plea to my academic colleagues and friends at business schools, departments of economics and MBA programmes all over the world:

Please let us not forget about the “Nature of Business- Transformational Change: Business inspired by nature”.

As noted throughout this Blog, a perfect storm of social, economic and environmental factors mean increased volatility for our working environments. In these transformational times our organisations are being challenged to ‘redesign for resilience’. As for example, Giles Hutchins in his book ‘The Nature of Business’ has so eloquently shown, organisations that seek out opportunities in these challenging times by redesigning for resilience are best able to survive and thrive the volatile times ahead. Firms of The Future are Businesses Inspired by Nature, applying ecological thinking for radical transformation at all levels of organisational design and behaviour.

Therefore, my friends, I invite you to design and offer modules on the relationship between a successful business and Mother Nature, the original entrepreneur, and the original guide to living wisely.

These modules should look at how nature is inspiring innovations that: increase energy and resource productivity; eliminate the concept of waste; catalyse the shift from product to service-oriented economies; build natural and social capital, and enhance business resilience. They should also provide an opportunity to think more philosophically about the natural world and our place within it, and to explore contested narratives about people and nature and how diverse perspectives are embedded in policies, institutions, leadership styles and business models.

In gratitude,

Your friend in humility,

Kamran Mofid

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 9071

Biomimicry: Mother Nature’s Guide to a Better and more Harmonious World

Learning fromNature

“With the onward march of science and technology, and the continuing quest for improvement, there is a growing curiosity about the world around us. The structures in nature are great lessons for human study. Only the most successful structural forms have survived. The resourcefulness of material use, conformity with mathematical proportion, underlying structural systems, and the profound capacity to respond to a variety of climatic and environmental forces, make natural forms tremendous exemplars to numerous aspects of our life. Close examination of structures in nature can be rewarding and surprising. “Doing it nature's way”, as shown below, has the potential to change the way we live for the better.

Biomimicry (from bios, meaning “life,” and mimesis, meaning “to imitate”) is a design principle that seeks sustainable solutions to human problems by consulting and emulating nature’s time- honoured patterns and strategies. According to Janine Benyus (2002), author of the ground breaking book Biomimicry, the core idea is that nature, imaginative by necessity, has already solved many of the problems we are grappling with. Using nature’s principles allow us to create products, processes, and policies that are well- adapted to life on Earth over the long haul.

'BT took inspiration from the behaviour of ants when it redesigned its phone network.'.

Photo:theguardian.com

The science of biomimicry provides us with a framework. In her book, Benyus offers the following nine basic laws of the circle of life, all of which resonate throughout her work and that of other biomimics:

• Nature runs on sunlight

• Nature uses only the energy it needs

• Nature fits form to function

• Nature recycles everything

• Nature rewards cooperation

• Nature banks on diversity

• Nature demands local expertise

• Nature curbs excesses from within

• Nature taps the power of limits”

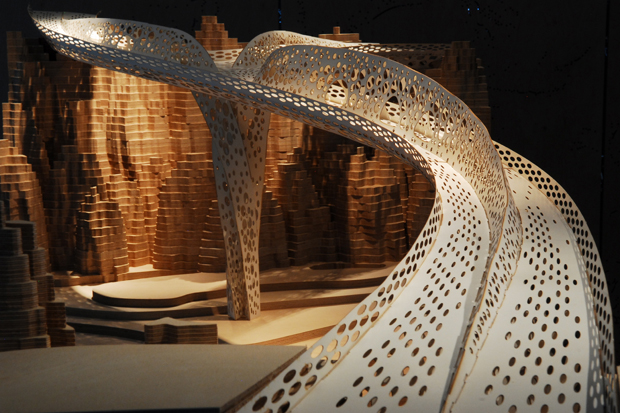

Shi Ling Bridge:Biomimicry in architecture and the start of the Ecological Age

Photo: wired.co.uk

‘Animals, plants and microbes are eternal engineers, possessing a power of innovation that humanity can merely watch in awe. They are in a constant flux of change, adapting and evolving to fit with the ever-changing world around them. With climate change now an accepted trend and scarcity of crucial resources becoming increasingly prevalent, what can business learn from this constant cycle of natural innovation?

Biomimicry is a new science that aims to use nature's best ideas and adapt them for human use. The environment has developed many of the world's most phenomenal masterpieces such as photosynthesis, self-sustaining eco-systems and natural selection, so how can humans copy these designs and manufacturing systems to solve some of today's biggest challenges?

Biomimicry looks at nature in three different ways:

• Nature as a model: Biomimicry uses the forms, processes, systems, and strategies employed by the natural world as inspiration for sustainable solutions.

• Nature as a measure: Looking at the standards set by nature, biomimicry aims to measure the sustainability of inventions using ecology as a benchmark.

• Nature as a mentor: The focus of biomimicry is not what we can extract from nature but what we can learn from it.’

“Mimesis within the context of its original Greek meaning requires the imitator to embody that which is being imitated. This goes to the heart of what makes us human: through perception, imagination and empathetic identification, we can share in what another feels and in doing so transform what we perceive into what we experience. It's wisdom sourced from our ability to love.

It is true that our analytical examination of nature is important, but only as part of a deeper, richer participatory engagement. If the deeper resonance of our nature is overlooked, such biomimetic transformations fail to address the root cause of our unsustainable way of life. We deal with symptoms (carbon emissions, waste to landfill, ocean dead zones, social inequality, factory farming) while neglecting the underlying cause (attuning our self-other-nature relationship).

Put more bluntly, scientific rationalism will not get us out of this mess on its own; in fact, it will only add to our dysfunctional way of living unless it goes hand-in-hand with a deeper participatory way of engaging with life: scientific, sensuous and spiritual.”

The above excerpts are from the following original articles:

Live discussion: What is Biomimicry? | Guardian Sustainable Business | theguardian.com