- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 3519

“The morality tale Ms Lagarde sets out is not a new one: feckless southern Europeans ran riot for the euro's first decade and now have to be bailed out from their mess”

“Not only should Christine Lagarde know better, she does know better. When the head of the IMF agreed in this paper on Saturday that the crisis across southern Europe was "payback time", she contravened both common sense and her own arguments. Imprudent borrowers require foolhardy lenders, and in Greece and elsewhere that role has often been played by northern European banks. In summer 2010, just as the eurozone crisis kicked off, the country whose banks were most exposed to Greece was France. Similarly, French banks were only just behind German institutions in their loans to Spain. By easing these huge flows of hundreds of billions across borders, the single currency played a material role in causing the continent's crisis.

Ms Lagarde knows all this. Indeed, as France's finance minister at the tail end of the boom, she must be held partly responsible.”… Editorial, The Guardian, 27 May 2012

It is in this spirit that I am most pleased that on Friday 25 May 2012, I had written the following Bolg:

The Moral Blindness of Northern Europe

Corruption, Tax avoidance and “Jobs for the Boys”: Only in Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal? Oh No!!

“As the euro and financial crises have deepened and worsened, Northern Europe has- shamelessly and arrogantly- linked mainly corruption, including tax avoidance and evasion, in Southern Europe as the pivotal reason for Europe’s economic crises. True or not true, this, cannot be the end of the story, as it gives rise to a false belief that Northern Europe is honest, ethical and not corrupt.

What we should remember is the fact that in Northern Europe they deviously manage to hide their corruption, misdeeds, and “jobs for the boys”, for example, by wrapping them in the mumbo jumbo of the efficient market economy, the need for deregulation and private sector is good, etc, etc.”…

Eurozone crisis: Ms Lagarde's morality tale

The Moral Blindness of Northern Europe

http://gcgi.info/kamrans-blog/178-the-moral-blindness-of-northern-europe

And now please see below!

Christine Lagarde, scourge of tax evaders, pays no tax

IMF boss who caused international outrage when she suggested that Greeks should pay their taxes earns a tax-free salary

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/may/29/christine-lagarde-pays-no-tax

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 22376

Photo:theguardian.com

Today, there is a great interest in highlighting a growing problem area, namely, the rapidly accelerating global corporate concentration of media ownership and the consequent grave impacts on democracies and consciousness throughout the world. It is very obvious that the performance of the mass media has recently become extremely degraded, with rampant commercialisation, trivialisation, corporate ownership, the PR industry and pressure groups agenda. This, as well as so much repetition, the narrow range of debate, and sharply declining standards for journalistic integrity, has significantly affected the possibilities of progress, development and education.

Lest we forget, a free and an independent media were conceived to serve the public good. Good journalism once stood at the heart of the struggle for freedom, democracy and justice, making it possible for responsible citizens to make informed decisions. This, as we all know, is not, by-and-large, true any more. Profit and share-holders values and interest are what matters most.

Given this increasing and overwhelming ownership of our global media outlets by individuals such as Rupert Murdoch and his cohorts, supported by corporate advertisers, compromising independent and responsible journalism, the time has arrived to seriously question if under these conditions the media indeed can be for the common good?

This is a pivotal moment in the life of our global community. We can see more clearly than ever that the threats of the twenty-first century spare no one. Climate change, the spread of disease and deadly weapons, and the scourge of terrorism all cross borders. There is also a major struggle for justice, freedom and democracy in many parts of the world. Moreover, given the financial meltdown of 2008, there is much demand for greater transparency, business and corporate social responsibility and more. Therefore, if we want to advance the global common good, we must secure global public goods.

Here is the moment for the global media to play a pivotal role in building a better world. Serving democracy and nourishing the common good is, for the media, something that requires not only attacking corrupt secrets in a society, but also defending non-corrupt communication. In short, in the world as it is today, the need for high-quality reporting is greater than ever before.

This in turn is the gist of my Blog for today: How to secure the financial and editorial independence of the media and its quality of production/reporting without party affiliation, PR pressure, etc; whilst remaining faithful to the liberal and progressive tradition and managed in an efficient and cost-effective manner.

In short, can the media be for the common good?

Photo:bing.com

The answer to this question is YES. To prove this, I am delighted to offer you The Guardian and The Observer, as examples. There are millions of words I can write to support my claim. However, the two following pieces will go a long way to clearly demonstrate this case:

Alan Rusbridger and Nick Davies, winners of the Media Society Award 2012

A profile of editor Alan Rusbridger and reporter Nick Davies, joint recipients of the 2012 Media Society Award for their revelations and coverage of the phone hacking story in the Guardian. Actor Hugh Grant pays tribute to their work exposing the scandal that shook Britain's establishment

Watch this excellent video:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/video/2012/may/25/alan-rusbridger-nick-davies-video-profile

The Scott Trust

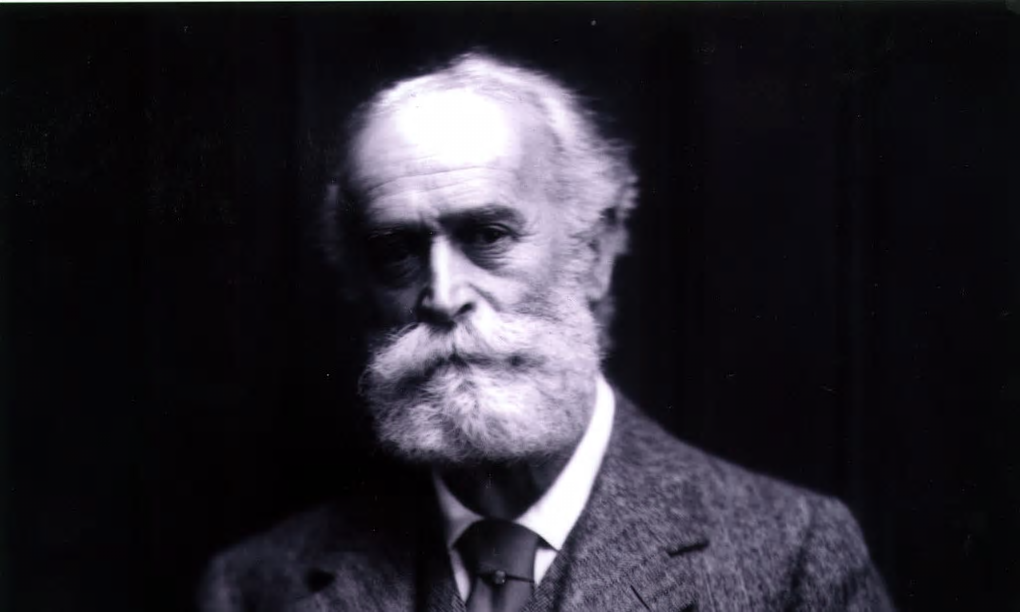

C P Scott Photo: the guardian.com

“The Scott Trust was formed in 1936, but the history of the Trust and Guardian Media Group began more than a century earlier with the launch of the Manchester Guardian on May 5, 1821.

The paper was founded by John Edward Taylor to promote the liberal interest in the aftermath of the Peterloo Massacre. Politically, Taylor was a reformer. His newspaper declared that it would ‘zealously enforce the principles of civil and religious Liberty… warmly advocate the cause of Reform… endeavour to assist in the diffusion of just principles of Political Economy and… support, without reference to the party from which they emanate, all serviceable measures’.”

A- Purpose

“The Manchester Guardian (now the Guardian) was founded in 1821 to promote the liberal interest in the aftermath of the Peterloo massacre. The newspaper gained an international reputation under long-serving editor and latterly owner CP Scott.

The Scott Trust was created in 1936 following the death of CP Scott and his son Edward in 1932. Edward’s brother John was left as the sole owner, and was faced with the threat of death duties, which would have crippled the business and jeopardised the future independence of the newspaper.

To avoid this, and to secure his father’s legacy of the Manchester Guardian’s independent liberal journalism, John Scott voluntarily renounced all financial interest in the business for himself and his family, putting all his shares – worth more than £1 million at the time – into a trust.”

B- Values

Fundamentally it implies honesty, cleanness, courage, fairness, a sense of duty to the reader and the community.-C. P. Scott

“The Manchester Guardian was founded in the liberal interest to support reform in the early 19th century. The ethos of public service has been part of the DNA of the newspaper and Group ever since.

C.P. Scott, the famous Manchester Guardian editor, outlined the paper’s principles in his celebrated A hundred years - an essay by C P Scott on May 5, 1921.

The much-quoted article is still used to explain the values of the present-day newspaper, Trust and group. It is also recognised around the world as the ultimate statement of values for a free press.

Among the many well known lines are the assertions that ‘Comment is free, but facts are sacred’, that newspapers have ‘a moral as well as a material existence’ and that ‘the voice of opponents no less than that of friends has a right to be heard’.

Now please compare and contrast the above with the following two statements:

“The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase Its Profits, whilst the businesses' sole purpose is to generate profit for shareholders” -Milton Friedman, Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences

"The only reliable, durable and perpetual guarantor of independence is profit." – James Murdoch, Chief, News Corp

I rest my case.

To discover more about the Guardian and the Scott Trust see:

The Scott Trust A unique form of media ownership

Related article:

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 4165

The social unrest, economic gloom and austerity in Europe today mirrors one of the greatest crises in British history

“The news from Europe is getting worse by the day: Economic gloom across the continent and multiple crises in the currency zone. With rising unemployment and inflation there are riots in the streets with forecasts of anarchy in some parts of Western Europe.

And along with the simmering discontent there is a worrying rise of radical groups and populist right wing movements. In the fringes, secessionists are pushing for independence, indeed for the break up of the whole European order under which we have all lived secure and comfortable for so long.

At home in Britain there are worrying signs in every town - cuts in public services have led to closures of public baths and libraries, the failure of road maintenance, breakdowns in the food supply and civic order.

While political commentators and church leaders talk about a "general decline in morality" and "public apathy", the rich retreat to their mansions and country estates and hoard their cash.

It all sounds eerily familiar doesn't it? But this is not Angela Merkel's eurozone - it is Roman Britannia towards the year 400, the period of the fall of the Roman Empire.”…

Read more:

- The Moral Blindness of Northern Europe

- Why Love, Trust, Respect and Gratitude Trumps Economics

- University Corruption and the Financial Crisis: The Theft of the Century by the Most 'Educated Thieves'- All with MBAs and PhDs!

- An Invitation to Attend the 2012 GCGI Annual Conference

- A Must Read Book: Inside Job