The state of our world today and the prophetic words of John Ruskin

'John Ruskin was the greatest critic of his age: a critic not only of art and architecture but of society and life. But his writings - on beauty and truth, on work and leisure, on commerce and capitalism, on life and how to live it - can teach us more than ever about how to see the world around us clearly and how to live it.'-Suzanne Fagence Cooper, Author, To See Clearly: Why Ruskin Matters

'He believed life should be beautiful, inequality was an outrage and that capitalism leads to aesthetic degradation. No wonder the quintessential Victorian speaks so powerfully to our times.'- Larry Ryan, The Guardian

‘God has lent us the earth for our life; it is a great entail. It belongs as much to those who are to come after us, and whose names are already written in the book of creation, as to us; we have no right, by any thing that we do or neglect, to involve them in unnecessary penalties, or deprive them of benefits which it was in our power to bequeath …’- John Ruskin

Ruskin, another legend who, like Wordsworth, was inspired by the Lake District.

“The first thing that I remember, as an event in life, was being taken by my nurse to the brow of Friar's Crag on Derwent Water; the intense joy, mingled with awe, that I had in looking through the hollows in the mossy roots, over the crag, into the dark lake, has associated itself more or less with all twining roots ever since."- John Ruskin

A view from Friar’s Crag and walk round Strandshag Bay, Derwent Water, Keswick. Ruskin described the view

from here as one of the three most beautiful scenes in Europe.-Photo: Andrew's Walks

‘The Lake District was central to the work of John Ruskin, who was a writer on art and architecture, a geologist and naturalist, a social commentator and an environmentalist. It was this remote and beautiful region which inspired his “ruling passion”: a love of landscape which encompassed the geology that shaped it and the living things that flourished in it, as well as its portrayal in art.

‘For Ruskin, both as a refuge and a resource, the Lake District became his home. From Brantwood, on the shores of Coniston Water, he followed Wordsworth's footsteps in preserving the region's fragile beauty for the education and enjoyment of future generations.’-’Ruskin and the Lake District, Lancaster University

Turner painting known as Ruskin's View

The watercolour by JMW Turner features a view from the churchyard in Kirkby Lonsdale. "I do not know in all my own country,

still less in France or Italy, a place more naturally divine.' -John Ruskin, in Fors Clavigera, Letter 52, April 1875

John Ruskin, Born: February 8, 1819, London Died: January 20, 1900, Brantwood, Lake District

In today’s era of overlapping ecological, environmental, social, economic, and cultural crises, Ruskin is more relevant than ever before. As well as providing early insight into the destructive and oppressive nature of many processes of industrialisation and capitalism, Ruskin provides us with alternative paths in our search for good, meaningful and rewarding life.

'John Ruskin: A Victorian visionary for today'

‘All literature, art, and science are in vain, and worse, if they do not enable you to be glad.’

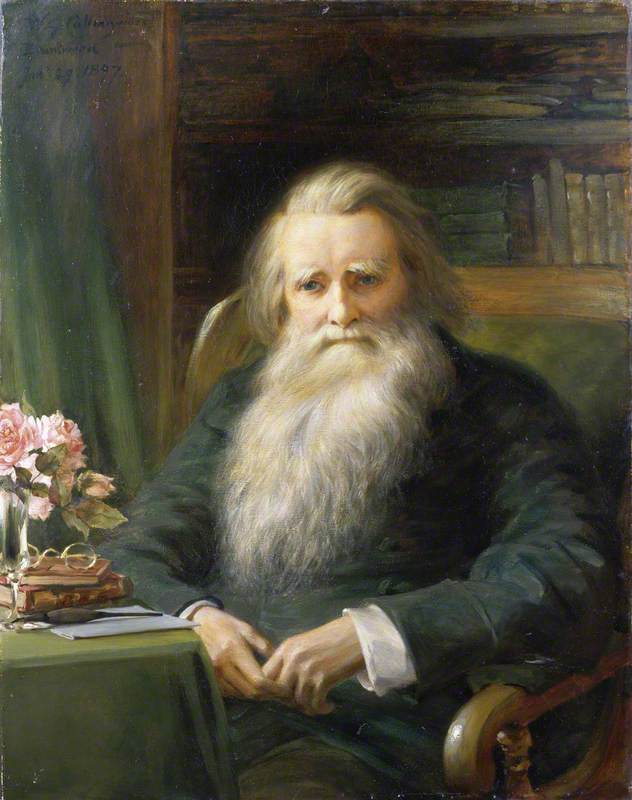

John Ruskin in a paintaing by William Gershom Collingwood (1854–1932). The Ruskin Museum

‘Ruskin shaped – and still shapes – the world we live in, the way we think and work, the environment, built and natural, that surrounds us, and many of the services we enjoy. Two hundred years after his birth, we live in ‘Ruskinland’.’

“Wherefore, when we build, let us think that we build forever. Let it not be for present delight, nor for present use alone; let it be such work as our descendants will thank us for, and let us think as we lay stone that a time will come when those stones will be held sacred, because our hands have touched them; and men will say, as they look upon the labour and wrought substances of them: ‘See this our fathers did for us.”-John Ruskin

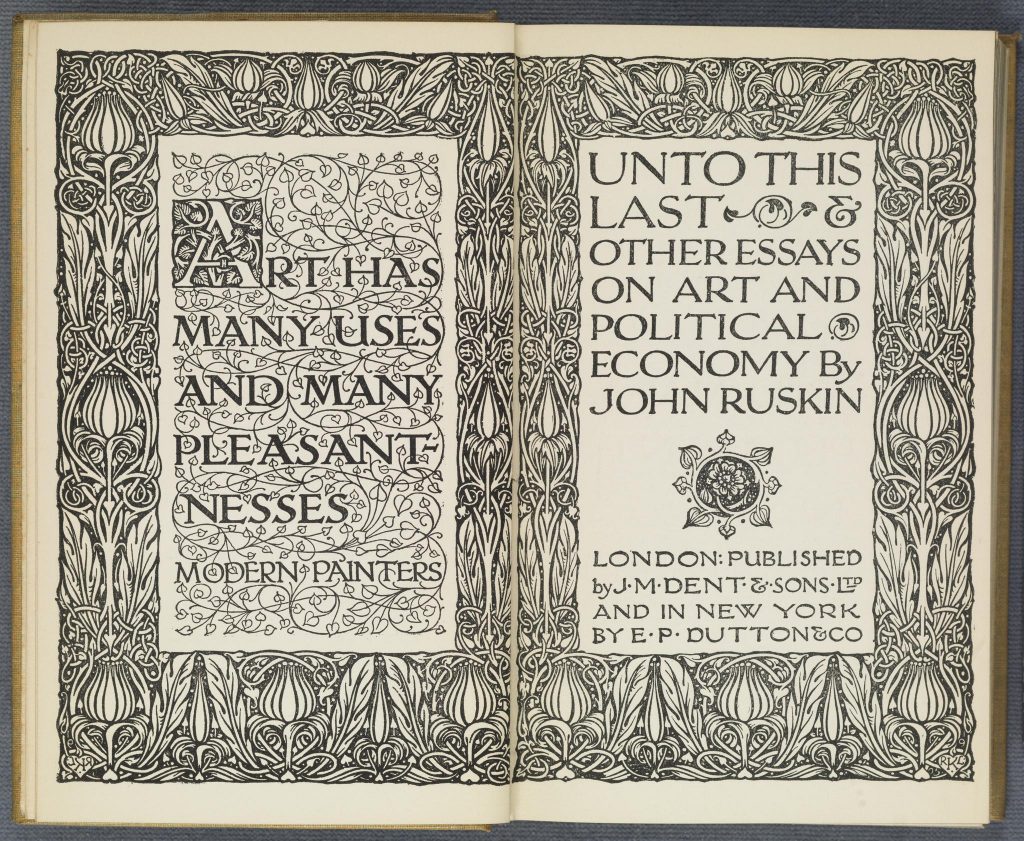

‘THERE IS NO WEALTH BUT LIFE. Life, including all its powers of love, of joy, and admiration. That country is the richest which nourishes the greatest number of noble and happy human beings; that man is richest who, having perfected the functions of his own life to the utmost, has also the widest helpful influence, both personal, and by means of his possessions, over the lives of others.’ [Library Edition 17.105]

- This passage comes from Unto This Last, four essays advocating an ethical and socially responsive economy, first published in 1860. It was the book by which Ruskin himself most wished to be remembered.

(Today, Ruskin’s works are largely out of print or available in abridged versions only. However, one of his most enduring, and perhaps his best, books is still available: Unto This Last, not a book of criticism but rather a series of four essays on social theory. The name comes from the Parable of the Vineyard in the New Testament, where Christ says “take that thine is, and go thy way: I will give unto this last even as unto thee.”)- Michael Norris

‘In sum, he is often described as a polymath, a man with many sides to his nature and achievements. For example, he was a superb artist and a consummate recorder of both the natural and cultural worlds. There was hardly a field of knowledge or a natural phenomenon which did not interest him and which he did not attempt to record – the structure of rocks, plants and trees, cloud formations, the movement of water, and so on.

His radical thinking embraced the roles of women, advocating total equality with men. He advocated free and appropriate education for all. He had prophetic ideas about conditions of employment, the nature of meaningful work, the need for good social housing, community health and well-being. The Slow Food Movement, the welfare state, the National Health Service and the Arts & Crafts Movement all owe much to Ruskin’s thinking and advocacy.

It is well-known that Mahatma Gandhi translated Ruskin’s book of four powerful essays advocating a socially responsive and moral economy, known to us as Unto This Last, into his native language. Less well known is the fact that he gave it the title Sarvodaya, which means ‘The welfare of all’. That phrase is the crux of Ruskin’s prophetic vision: the welfare of all.’-Peter Burman Ruskin lecture, Malta, 9th Feb 2020

See also: Unto this Last: John Ruskin’s Economic and Political Writings

...And indeed this is the tragedy of our time: How many of our so-called political, economic and business leaders have ever read Ruskin’s book of essays Unto This Last, or indeed, how many current university students have Ruskin on their reading list? Think about it. This is the answer to many peoples question: Why is our world in such a big mess?

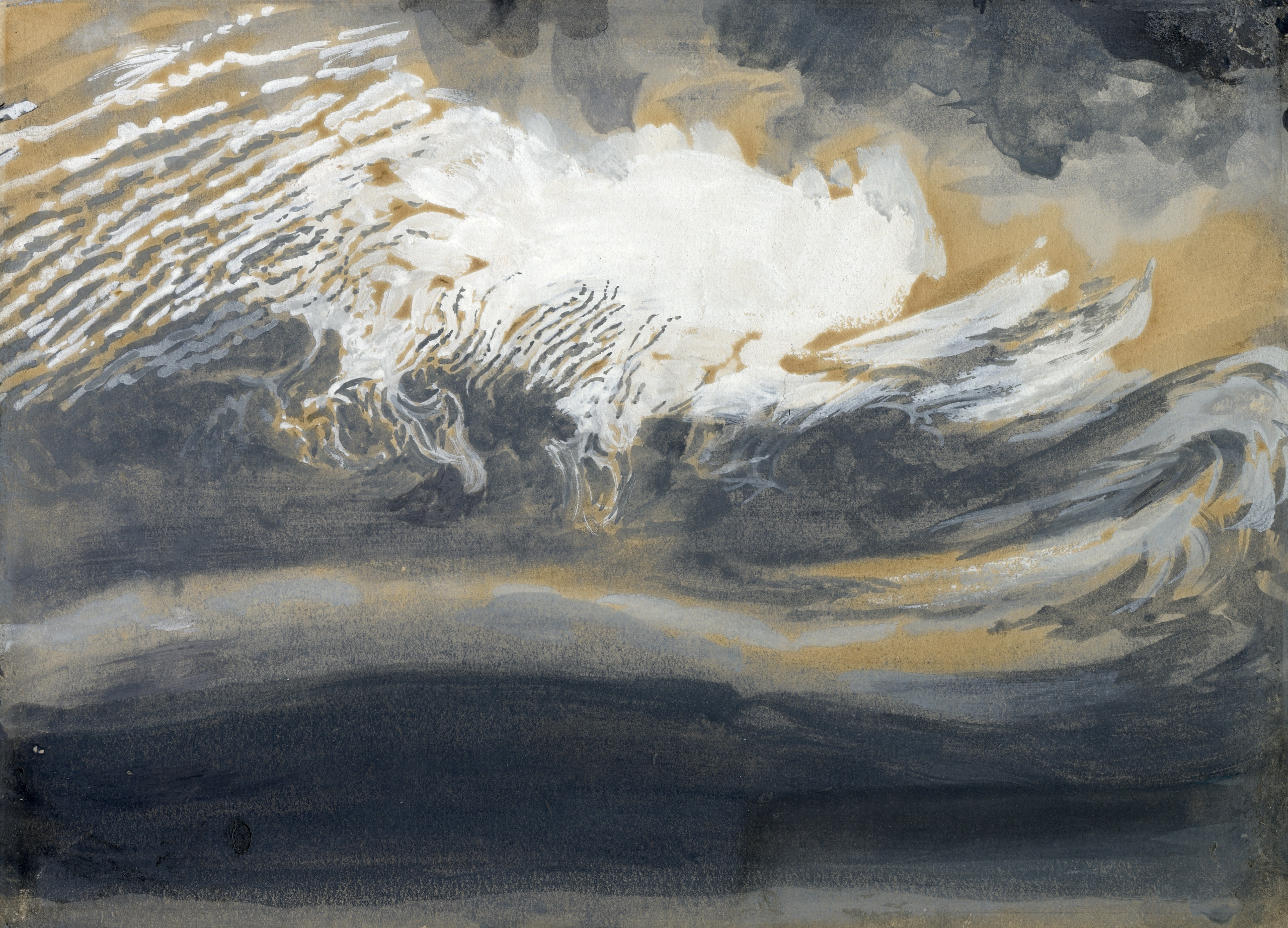

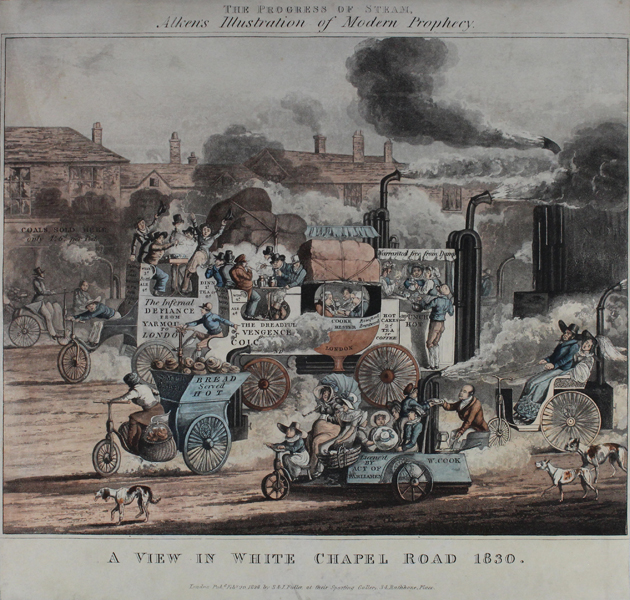

‘His deep love of nature led him to document every aspect of the natural world, from vast mountainous landscapes to the smallest plants and rocks. In doing so, Ruskin unearthed a worrying and accelerating trend. The glaciers of his beloved Alps appeared to be receding, the facades of his favourite buildings were slowly eroding away, and the air outside his window had become thick with a dark, sluggish haze, of ‘which no ray of sunshine can pierce.’

Ruskin realised he was witnessing the ravages of climate change, a phenomenon which he attributed to the ‘plague cloud of chimney smoke flying hellishly over the whole sky.’ He would dedicate his life to capturing the gradual, perishing beauty of his favourite landscapes, attempting to bring attention to what he termed ‘the Storm Cloud of the Nineteenth Century.’

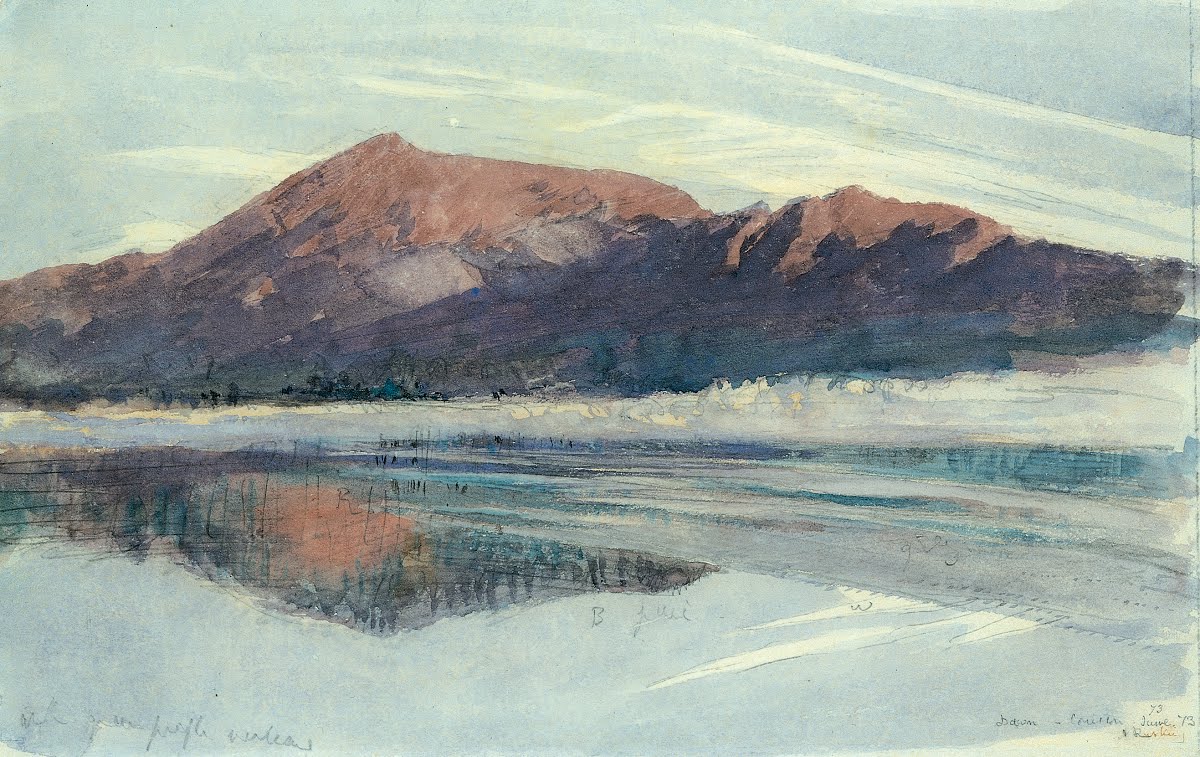

John Ruskin, Ice Clouds over Coniston Old Man (c.1880)-Library, Museum and Research Centre, University of Lancaster.

Lest We Forget

‘The first time John Ruskin noticed the gray clouds of the “plague-wind” was in 1871, decades into the industrial era. Walking home from work at the University of Oxford one spring day, the renowned English art critic looked skyward, to the “dry black veil which no ray of sunshine” could penetrate, and then back to earth, where the leaves of trees shook “not violently, but enough to show the passing to and fro of a strange, bitter, blighting wind.” Only the wind proved not to be so strange. In the months that followed, he repeatedly witnessed the same weather pattern.

That July, the 52-year-old Ruskin committed his observations to writing. Never in a lifetime of monitoring nature’s movements had he seen such springs and summers. The origins of this mysterious meteorological change demanded scientific investigation, he argued. Where did the plague-wind come from? Was it caused by the smoky belch of heavy industry, or another source? With rigorous scientific experimentation, could the wind be made to consist of something else?

The scientific men are busy as ants, examining the sun and the moon, and the seven stars, and can tell me all about them, I believe, by this time; and how they move, and what they are made of.

And I do not care, for my part, two copper spangles how they move, nor what they are made of. I can’t move them any other way than they go, nor make them anything else, better than they are made. But I would care much and give much, if I could be told where this bitter wind comes from, and what it is made of.

For, perhaps, with forethought, and fine laboratory science, one might make it from something else.

It looks partly as if it were made of poisonous smoke; very possibly it may be: there are at least two hundred furnace chimneys in a square of two miles on every side of me. But mere smoke would not blow to and fro in that wild way. It looks more to me as if it were made of dead men’s souls—such as are not gone yet where they have to go, and may be flitting hither and thither, doubting, themselves, of the fittest place for them.

Ruskin cited these musings in an 1884 lecture in London on “the plague-wind of the eighth decade of years in the nineteenth century; a period which will assuredly be recognized in future meteorological history as one of phenomena hitherto unrecorded in the courses of nature.” The lecture is often read as one of the earliest expressions of modern environmentalism…’-A 19th-Century Glimpse of a Changing Climate

...‘Ruskin was appalled by the way industrialization dehumanized workers, stifled creativity and polluted the environment. Using lectures and open letters, he encouraged workers to improve their lives through self-education. He founded a drawing school in Oxford (now known as The Ruskin School of Art), and he created one of Britain’s first regional museums, in Sheffield, in northern England. His watercolors, inimitably capturing the delicacy of a single flower or a gothic facade, celebrated the beauty of both divine and human creation.

But for Ruskin, the pen was always mightier than the brush. He was an extraordinarily prolific writer. The official Library Edition of his works runs to a forbidding 39 volumes. Of this prodigious output, only “Unto This Last,” his ferocious critique of laissez-faire capitalism, and his autobiography, “Praeterita,” remain readily available in print.

“He’s a dazzling intellectual and an enormously great writer, but other things in his life have got in the way,” said the scholar Clive Wilmer, referring to the current fixation with Ruskin’s sexuality. Mr. Wilmer is master of the Guild of St. George, a charity Ruskin founded in Sheffield in the 1870s to give practical application to his utopian ideas…

Robert Hewison, author or editor of more than a dozen books on Ruskin, said in an interview that Ruskin was the first major literary figure to write about pollution and climate change.

In an 1884 lecture to the London Institution, “The Storm-Cloud of the 19th Century,” Ruskin spoke of a “Thunderstorm; pitch dark, with no blackness — but deep, high, filthiness of lurid, yet not sublimely lurid, smoke-cloud; dense manufacturing mist.” He was describing a new meteorological phenomenon he called the “plague wind,” tainted with soot from a nearby steel factory, observed at his home in the Lake District in northwest England.

“This and his observations on glaciers are something that make him a justified prophet,” Mr. Hewison said. “Pollution was emblematic of the corruption in contemporary capitalism, the destruction of nature by man and his greed.”

Quoting Ruskin’s “Unto This Last,” Mr. Hewison added, “He famously wrote ‘there is no wealth but life,’ and his attack on liberal economics could just as easily be a critique of neoliberalism now.”- Excerpts from an article by Scott Reyburn, New York Times, 5 February 2019

"In Unto This Last (1862), Ruskin turned to attack the economic system that he believed produced such despairing, inhuman relations of men in society. Unto This Last, whose four chapters first appeared in 1860 as articles in the Cornhill, consolidates the political position Ruskin had been evolving during the previous decade and sets forth the ideas he would continue to advance in Munera Pulveris (1862-3), The Crown of Wild Olive (1866), Time and Tide (1867), and Fors Clavigera (1871-84). Most contemporary readers found both Ruskin's general attitudes and his specific proposals so outrageous that they concluded that he must have been struck mad. Today, his political proposals, like his emphases on communal responsibility, the dignity of labour, and the quality of life, have had such influence that they no longer appear particularly novel. In the beginning of Unto This Last, as in Modern Painters, Ruskin confronts the so-called experts and denies the relevance of their ideas. Whereas classical economists proceeded on the assumption that men always exist in conditions of scarcity, Ruskin, who realized that a new political economy was demanded by new conditions of production and distribution, argues that his contemporaries in fact exist in conditions of abundance and that therefore the old notions of Malthus, Ricardo, Mill, and others are simply irrelevant. According to him, then, "the real science of political economy, which has yet to be distinguished from the bastard science, as medicine from witchcraft, and astronomy from astrology, is that which teaches nations to desire and labour for the things that lead to life: and which teaches them to scorn and destroy the things that lead to destruction." John Ruskin-'Unto This Last'

Ruskin explaining the bastard science

'I believe that I discovered some of my deepest convictions reflected in this great book of Ruskin and that is why it so captured me and made me transform my life.'-Mahatma Gandhi

As noted above, Ruskin's work and writings have influnced many social reformers and activists, amongst them Gandhi, who was particularly influenced by Unto This Last, which he translated into Gujarati and used as a basis for his own political and economic theory. In his translation, titled Sarvodaya.

‘Gandhi received a copy of Ruskin's Unto This Last from a British friend, Mr. Henry Polak, while working as a lawyer in South Africa in 1904. In his Autobiography, Gandhi remembers the twenty-four-hour train ride to Durban (from when he first read the book), being so in the grip of Ruskin's ideas that he could not sleep at all: "I was determined to change my life in accordance with the ideals of the book." As Gandhi construed it, Ruskin's outlook on political-economic life extended from three central tenets: That

- the good of the individual is contained in the good of all.

- a lawyer's work has the same value as the barber's in as much as all have the same right of earning their livelihood from their work.

- a life of labour, i.e., the life of the tiller of the soil and the handicraftsman is the life worth living.

The first of these I knew. The second I had dimly realized. The third had never occurred to me. Unto This Last made it clear as daylight for me that the second and third were contained in the first. I arose with the dawn, ready to reduce these principles to practice…’-Wikipedia

John Ruskin: Chasing the Storm Cloud

“My most intense happinesses have of course been among mountains.”

John Ruskin 1862, ‘View from my Window in Mornex, Where I stayed a While 1861-62’

'Ruskin’s enduring fascination with nature began as a young man. At the age of fourteen, he travelled with his parents across France, Switzerland and Italy, taking in the mountain ranges of the Alps and the ancient palazzos of Venice.

Mountains became a favourite subject of Ruskin’s and he continued to be drawn to them for the rest of his life – ‘it is always the same with mountains,’ he said, ‘once you have lived with them for any length of time, you belong to them. There is no escape.’

‘Go to nature in all singleness of heart, and walk with her laboriously and trustingly

… rejoicing always in the truth.’

John Ruskin 1847, Study of Rocks and Ferns Crossmount Perthshire

At the heart of Ruskin’s artistic philosophy was a need to capture the truth of nature’s beauty.

Realistically representing each and every phenomenon.

'Inspired by the works of his idol, J.M.W. Turner, Ruskin made many detailed studies, attempting to capture the minute details of everything he encountered. It was through this process of truthful representation that Ruskin discovered the effects of the changing climate. Returning again and again to places he had drawn, he noticed the slow degradation of their natural environments, by what he asserted was ‘violent and definite physical action.’

Ruskin was convinced that the answer to all this destruction lay within the clouds.

'In a series of lectures he gave entitled ‘the Storm Cloud of the Nineteenth Century’, he spoke of how the clouds of years gone by had been ‘luxuriously fine’, but that now a ‘thunderstorm; pitch dark, with no blackness’ was frequenting the sky.

Ruskin believed the belching chimneys of modern industry were creating these ‘filthy, lurid’ clouds, and that they themselves were to blame for the decline in nature’s beauty.

The Progress of Steam, Alken's Illustration of Modern Prophecy. A View in White Chapel Road 1830

'In his later years, Ruskin fell into a deep depression. The anguish of the changing climate, mixed with the failure of his marriage and the loss of his parents, proved almost too much for Ruskin to bare. He retreated to Brantwood, his Lake District home on the edge of Coniston Water, where he found some solace in the beauty of the lake and the clouds.

He described the sunlight over Coniston as ‘a painted window into heaven.’

'Though Ruskin spent much of his life chasing the effects of ‘the Storm Cloud’, his observations on climate change would not be proven and accepted till decades after his death. His works and writings remain an important insight into the history of Europe’s changing industrial landscape, and his philosophies have inspired many artists to continue in his stead.

John Ruskin, 1873, Dawn, Coniston

(The above excerpts courtesy of LakeLand Arts, Abbot Hall, Kendal, Cumbria, Lake District, England)

Read and discover more about John Ruskin:

Researchers explore John Ruskin’s ‘Storm Cloud’ in 200 year celebration

A 19th-Century Glimpse of a Changing Climate

A Storm Is Blowing - The Paris Review

John Ruskin: Prophet of the Anthropocene

John Ruskin: a Victorian visionary for today

Ruskin the radical: why the Victorian thinker is back with a vengeance

John Ruskin and the National Gallery

BRANTWOOD – THE WORLD OF JOHN RUSKIN-A PARADISE OF ART & NATURE

Two Must-read Books

Who was John Ruskin? What did he achieve - and how? Where is he today? One possible answer: almost everywhere. John Ruskin was the Victorian age's best-known and most controversial intellectual. He was an art critic, a social activist, an early environmentalist; he was also a painter, writer, and a determined tastemaker in the fields of architecture and design. His ideas, which poured from his pen in the second half of the 19th century, sowed the seeds of the modern welfare state, universal state education and healthcare free at the point of delivery. His acute appreciation of natural beauty underpinned the National Trust, while his sensitivity to environmental change, decades before it was considered other than a local phenomenon, fuelled the modern green movement. His violent critique of free market economics, Unto This Last, has a claim to be the most influential political pamphlet ever written. Ruskin laid into the smug champions of Victorian capitalism, prefigured the current debate about inequality, executive pay, ethical business and automation. Gandhi is just one of the many whose lives were changed radically by reading Ruskin, and who went on to change the world. This book, timed to coincide with the 200th anniversary of John Ruskin's birth in 2019, will retrace Ruskin's steps, telling his life story and visiting the places and talking to the people who - perhaps unknowingly - were influenced by Ruskin himself or by his profoundly important ideas. What, if anything, do they know about him? How is what they do or think linked to the vivid, difficult but often prophetic pronouncements he made about the way our modern world should look, live, work and think? As important, where - and why - have his ideas been swept away or displaced, sometimes by buildings, developments and practices that Ruskin himself would have abhorred? Part travelogue, part quest, part unconventional biography, this book will attempt to map Ruskinland: a place where, two centuries after John Ruskin's birth, more of us live than we know.'

Purchase this book HERE

Photo:Bookshop

'John Ruskin - born 200 years ago, in February 1819 - was the greatest critic of his age: a critic not only of art and architecture but of society and life. But his writings - on beauty and truth, on work and leisure, on commerce and capitalism, on life and how to live it - can teach us more than ever about how to see the world around us clearly and how to live it.

Dr Suzanne Fagence Cooper delves into Ruskin's writings and uncovers the dizzying beauty and clarity of his vision. Whether he was examining the exquisite carvings of a medieval cathedral or the mass-produced wares of Victorian industry, chronicling the beauties of Venice and Florence or his own descent into old age and infirmity, Ruskin saw vividly the glories and the contradictions of life, and taught us how to see them as well.'

Purchase this book HERE

GCGI is our journey of hope and the sweet fruit of a labour of love. It is free to access, and it is ad-free too. We spend hundreds of hours, volunteering our labour and time, spreading the word about what is good and what matters most. If you think that's a worthy mission, as we do—one with powerful leverage to make the world a better place—then, please consider offering your moral and spiritual support by joining our circle of friends, spreading the word about the GCGI and forwarding the website to all those who may be interested.

John Ruskin at Coniston

Coniston Water ( Image: Getty Images)

'In 1872 John Ruskin settled in the area, having bought his house, Brantwood, a year previously. Ruskin lived for the last 30 years of his life there, just across the lake from Coniston Village. When he died, he was buried in St Andrew’s Church graveyard, and his grave was marked with a large carved cross made from green slate from the local quarry at Tilberthwaite. It was designed by W.G. Collingwood his friend and secretary, who was an expert on Anglo-Saxon crosses, with symbols depicting important aspects of Ruskin’s work and life.

A year later W.G. Collingwood worked to set up an exhibition, now called the Ruskin Museum at the back of the Coniston Mechanics Institute, as a place to preserve any Ruskin mementos that could be found.'

Meet William Morris, Britain's most inspiring designer who was highly inspired by John Ruskin

‘Morris shared Ruskin’s belief in the superiority of medieval crafts. He imbibed Ruskin’s conviction that a nation can be judged by its aesthetic productions; that an immoral nation is incapable of creating great art; and that only non-mechanical, freely creative crafts could produce genuine beauty….

‘In Morris’s fictional utopia, News From Nowhere, contented citizens lived in creative harmony amidst beautiful landscapes while effortlessly producing exquisitely beautiful goods and a plenitude of necessities. They do so because their shared commitment to socialism rested on fundamental principles of egalitarianism and libertarianism. Whether such a society is possible in reality remains an open question, but Ruskin’s Guild certainly offered the painful lesson that it is simply impossible to combine ideals of free, creative labour with authoritarian power structures.’-The Ruskin–Morris Connection

The beauty of living simply: the forgotten wisdom of William Morris

Photo:bmhonline.wordpress.com