Photo: youtube.com

‘Zoroastrianism shaped one of the ancient world’s largest empires—the mighty Persian Empire. It was the state religion of three major Persian dynasties.

Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, was a devout Zoroastrian. By most accounts, Cyrus was a tolerant ruler who allowed his non-Iranian subjects to practice their own religions. He ruled by the Zoroastrian law of asha (truth and righteousness) but didn’t impose Zoroastrianism on the people of Persia’s conquered territories.

The beliefs of Zoroastrianism were spread across Asia via the Silk Road, a network of trading routes that spread from China to the Middle East and into Europe.

Some scholars say that tenets of Zoroastrianism helped to shape the major Abrahamic religions—including Judaism, Christianity and Islam—through the influence of the Persian Empire.

Cradle of god: Spirituality in the Land of the Noble

Zoroastrian concepts, including the idea of a single god, heaven, hell and a day of judgment, may have been first introduced to the Jewish community of Babylonia, where people from the Kingdom of Judea had been living in captivity for decades…’

Photo: The Prophet Zoroaster

‘Talk of ‘us’ and ‘them’ has long dominated Iran-related politics in the West. At the same time, Christianity has frequently been used to define the identity and values of the US and Europe, as well as to contrast those values with those of a Middle Eastern ‘other’. Yet, a brief glance at an ancient religion – still being practised today – suggests that what many take for granted as wholesome Western ideals, beliefs and culture may in fact have Iranian roots.’ More on this a bit later.

First, I wish to share something personal and very dear to me with you.

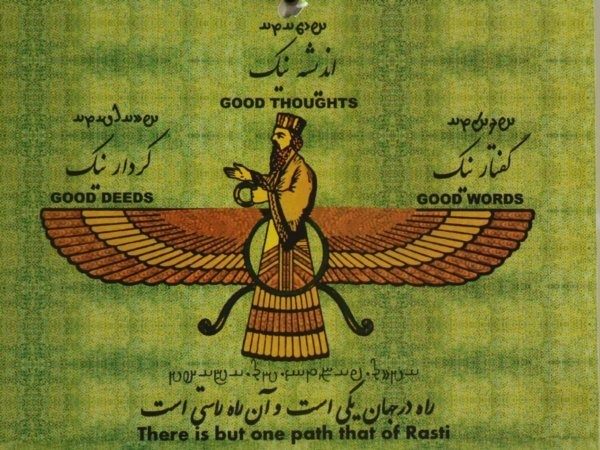

Think Good, Speak Good, Do Good

Photo:quora.com

Doing Good is a simple and universal vision. A vision to which each and every one of us can connect and contribute to its realisation. A vision based on the belief that by doing good deeds, positive thinking and affirmative choice of words, feelings and actions, we can enhance goodness in the world.

How true these beautiful and timeless words are. I learnt them well in my formative years, growing up in Tehran. We lived in Tehran Pars (Parsi Tehran), a mainly Zoroasterian founded and developed neighborhood inside the greater area of Tehran and located in the north east area of the city.

I attended Zoroasterian school- just a few meters away from the Rostam Bagh Fire Temple- and every morning we started our day by attending the morning assembly and reciting loudly: Think Good, Speak Good, Do Good.

This has served me well in my life. I cannot be grateful and thankful enough for those early years, growing up in Tehran Pars

A brief introduction to the beginnings of Tehran Pars

Rostam Bagh Fire Temple, Tehran Pars, Tehran. Photo: Ajam Media Collective

‘Arbab Rustam Guiv (1888-1980 CE) was a native of Yazd. His father Shahpur Guiv had a business in Yazd selling local hand made cloth. Arbab Guiv moved to Tehran to join his brother and made his fortune in trading, manufacturing and land. He converted a 150 to 200 acre parcel of fallow land at the foot of the Damavand mountain, some hundred kilometres north of Tehran, into fertile land where he cultivated fruits, vegetables and grain. He called his oasis Rustamabad. He added to his land holdings by purchasing another tract of land ten kilometres from Rustamabad.

During a 1953 trip to India, Arbab Guiv was very impressed with the housing colonies built for low and middle income Zoroastrians by wealthy benefactors. He was particularly impressed by Khosrow Bagh in Colaba, Bombay (Mumbai) and used it as a model for constructing a housing colony for Iranian Zoroastrians in Tehran. With this in mind, he purchased at a reduced cost fifteen acres of a new development by the Tafti and Aresh families in the north-east of Tehran, called Tehran Pars. On the land he purchased, Arbab Guiv a housing colony of 80 duplexes (160 units) called Rustam Bagh (or Rostam Baug). The units were then made available for low and middle income Zoroastrians. The colony included gardens, a community hall, library, school, sports ground and fire temple.’- Read more

Now, reverting to the main theme of this Blog: Zoroastrianism the ancient religion of Persia that has shaped the world

‘It is generally believed by scholars that the ancient Iranian prophet Zarathustra (known in Persian as Zartosht and Greek as Zoroaster) lived sometime between 1500 and 1000 BC. Prior to Zarathustra, the ancient Persians worshipped the deities of the old Irano-Aryan religion, a counterpart to the Indo-Aryan religion that would come to be known as Hinduism. Zarathustra, however, condemned this practice, and preached that God alone – Ahura Mazda, the Lord of Wisdom – should be worshipped. In doing so, he not only contributed to the great divide between the Iranian and Indian Aryans, but arguably introduced to mankind its first monotheistic faith.

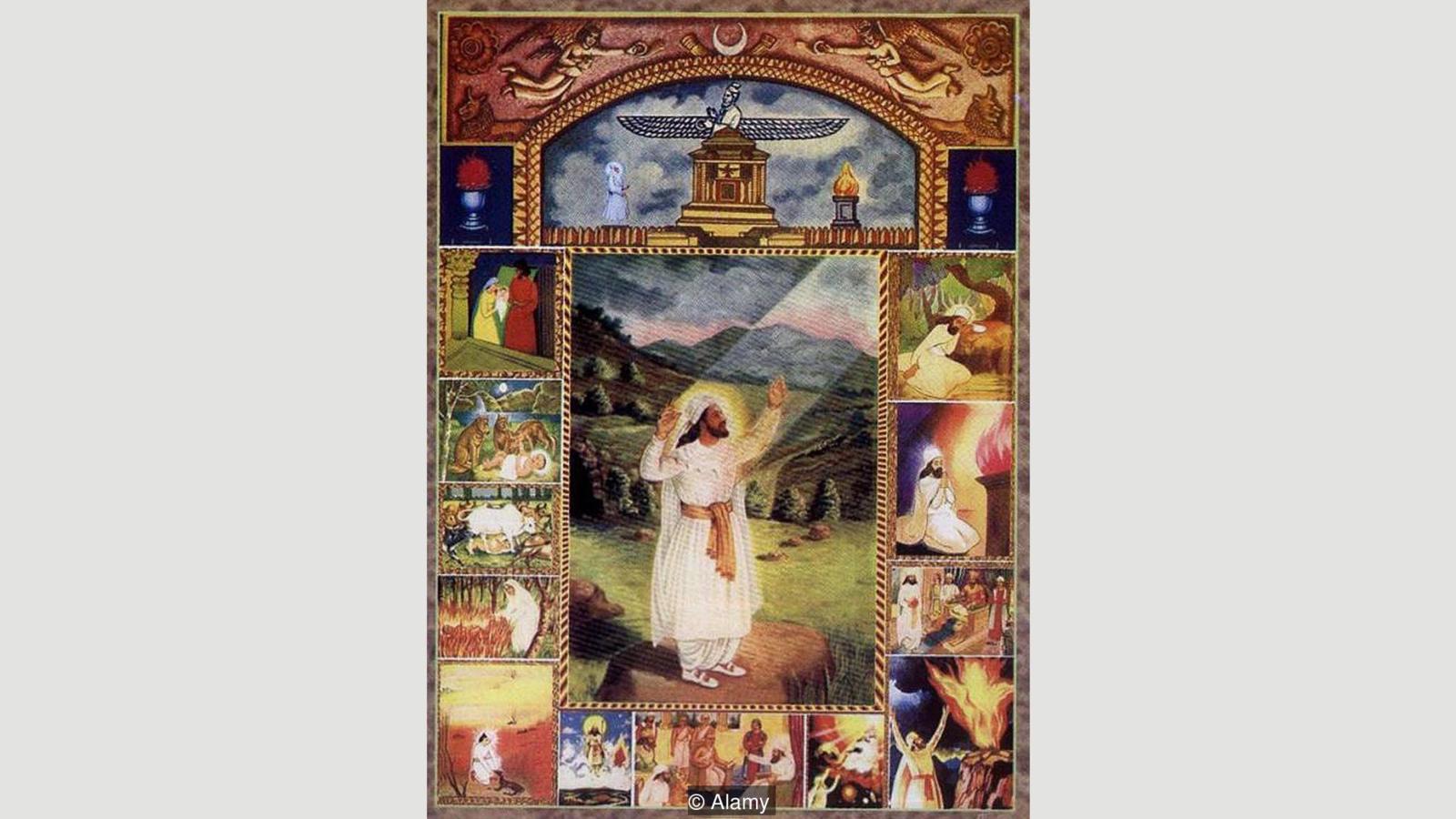

Photo:iraniantours.com

The idea of a single god was not the only essentially Zoroastrian tenet to find its way into other major faiths, most notably the ‘big three’: Judaism, Christianity and Islam. The concepts of Heaven and Hell, Judgment Day and the final revelation of the world, and angels and demons all originated in the teachings of Zarathustra, as well as the later canon of Zoroastrian literature they inspired. Even the idea of Satan is a fundamentally Zoroastrian one; in fact, the entire faith of Zoroastrianism is predicated on the struggle between God and the forces of goodness and light (represented by the Holy Spirit, Spenta Manyu) and Ahriman, who presides over the forces of darkness and evil. While man has to choose to which side he belongs, the religion teaches that ultimately, God will prevail, and even those condemned to hellfire will enjoy the blessings of Paradise (an Old Persian word).

How did Zoroastrian ideas find their way into the Abrahamic faiths and elsewhere? According to scholars, many of these concepts were introduced to the Jews of Babylon upon being liberated by the Persian emperor Cyrus the Great. They trickled into mainstream Jewish thought, and figures like Beelzebub emerged. And after Persia’s conquests of Greek lands during the heyday of the Achaemenid Empire, Greek philosophy took a different course. The Greeks had previously believed humans had little agency, and that their fates were at the mercy of their many gods, who often acted according to whim and fancy. After their acquaintance with Iranian religion and philosophy, however, they began to feel more as if they were the masters of their destinies, and that their decisions were in their own hands.

Though it was once the state religion of Iran and widely practised in other regions inhabited by Persian peoples (eg Afghanistan, Tajikistan and much of Central Asia), Zoroastrianism is today a minority religion in Iran, and boasts few adherents worldwide. The religion’s cultural legacy, however, is another matter. Many Zoroastrian traditions continue to underpin and distinguish Iranian culture, and outside the country, it has also had a noted impact, particularly in Western Europe.

Zoroastrian rhapsody

Centuries before Dante’s Divine Comedy, the Book of Arda Viraf described in vivid detail a journey to Heaven and Hell. Could Dante have possibly heard about the cosmic Zoroastrian traveller’s report, which assumed its final form around the 10th Century AD? The similarity of the two works is uncanny, but one can only offer hypotheses.

Elsewhere, however, the Zoroastrian ‘connection’ is less murky. The Iranian prophet appears holding a sparkling globe in Raphael’s 16th Century School of Athens. Likewise, the Clavis Artis, a late 17th/early 18th-Century German work on alchemy was dedicated to Zarathustra, and featured numerous Christian-themed depictions of him. Zoroaster “came to be regarded [in Christian Europe] as a master of magic, a philosopher and an astrologer, especially after the Renaissance," says Ursula Sims-Williams of the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London.

Today, mention of the name Zadig immediately brings to mind the French fashion label Zadig & Voltaire. While the clothes may not be Zoroastrian, the story behind the name certainly is. Written in the mid-18th Century by none other than Voltaire, Zadig tells the tale of its eponymous Persian Zoroastrian hero, who, after a series of trials and tribulations, ultimately weds a Babylonian princess. Although flippant at times and not rooted in history, Voltaire’s philosophical tale sprouted from a genuine interest in Iran also shared by other leaders of the Enlightenment. So enamoured with Iranian culture was Voltaire that he was known in his circles as ‘Sa’di’. In the same spirit, Goethe’s West-East Divan, dedicated to the Persian poet Hafez, featured a Zoroastrian-themed chapter, while Thomas Moore lamented the fate of Iran’s Zoroastrians in Lalla Rookh.

It wasn’t only in Western art and literature that Zoroastrianism made its mark; indeed, the ancient faith also made a number of musical appearances on the European stage.

In addition to the priestly character Sarastro, the libretto of Mozart’s The Magic Flute is laden with Zoroastrian themes, such as light versus darkness, trials by fire and water, and the pursuit of wisdom and goodness above all else. And the late Farrokh Bulsara – aka Freddie Mercury – was intensely proud of his Persian Zoroastrian heritage. “I’ll always walk around like a Persian popinjay,” he once remarked in an interview, “and no one’s gonna stop me, honey!” Likewise, his sister Kashmira Cooke in a 2014 interview reflected on the role of Zoroastrianism in the family. “We as a family were very proud of being Zoroastrian,” she said. “I think what [Freddie’s] Zoroastrian faith gave him was to work hard, to persevere, and to follow your dreams.”

Ice and fire

When it comes to music, though, perhaps no single example best reflects the influence of Zoroastrianism’s legacy than Richard Strauss’ Thus Spoke Zarathustra, which famously provided the booming backbone to much of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. The score owes its inspiration to Nietzsche’s magnum opus of the same name, which follows a prophet named Zarathustra, although many of the ideas Nietzsche proposes are, in fact, anti-Zoroastrian. The German philosopher rejects the dichotomy of good and evil so characteristic of Zoroastrianism – and, as an avowed atheist, he had no use for monotheism at all.

Zoroastrianism may have been the first monotheistic religion, and its emphasis on dualities, such as heaven and hell,

appear in Judaism, Christianity and Islam (Credit: Alamy) via the BBC

Freddie Mercury and Zadig & Voltaire aside, there are other overt examples of Zoroastrianism’s impact on contemporary popular culture in the West. Ahura Mazda served as the namesake for the Mazda car company, as well as the inspiration for the legend of Azor Ahai – a demigod who triumphs over darkness – in George RR Martin’s Game of Thrones, as many of its fans discovered last year. As well, one could well argue that the cosmic battle between the Light and Dark sides of the Force in Star Wars has, quite ostensibly, Zoroastrianism written all over it.

For all its contributions to Western thought, religion and culture, relatively little is known about the world’s first monotheistic faith and its Iranian founder. In the mainstream, and to many US and European politicians, Iran is assumed to be the polar opposite of everything the free world stands for and champions. Iran’s many other legacies and influences aside, the all but forgotten religion of Zoroastrianism just might provide the key to understanding how similar ‘we’ are to ‘them’.

*The above piece by Joobin Bekhrad was first published by the BBC-Culture on 6 April 2017.

Related reading:

Modern Iran: The Most Misunderstood Country

Cradle of god: Spirituality in the Land of the Noble

Revisiting the Persian cosmopolis: The World Order and the Dialogue of Civilisations

The Struggle for Human Rights on the Human Rights Day

Revisiting the Persian cosmopolis: The World Order and the Dialogue of Civilisations