Mother Earth as Healer and Teacher

Rhythms of Nature Ushering in a Better World

Goddess Gaia

‘Quite simply, Gaia is life. She is all, the very soul of the earth. She is a goddess who, by all accounts, inhabits the planet,

offering life and nourishment to all her children.

In the ancient civilizations, she was revered as mother, nurturer and giver of life. It’s she who created and sustained us,

and to whom we returned upon death.'-Greeting Goddess Gaia Image via Mystic Investigations

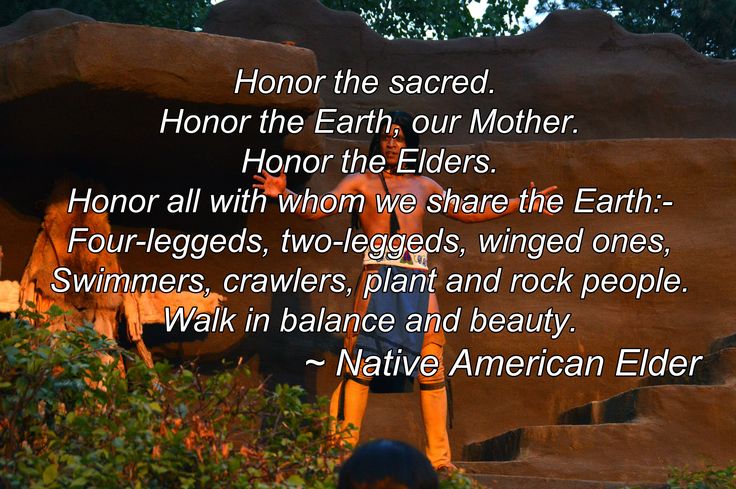

‘Earth Is A Mother Who Never Dies’- A saying from the Diné (or Navajo) people

"You must teach your children that the ground beneath their feet is the ashes of our grandfathers. So that they will respect the land, tell your children that the earth is rich with the lives of our kin.

"Teach your children what we have taught our children -- that the earth is our mother. Whatever befalls the earth, befalls the sons of the earth. If men spit upon the ground, they spit upon themselves.

"This we know. The earth does not belong to man; man belongs to the earth. This we know. All things are connected like the blood which unites one family. All things are connected.

"Whatever befalls the earth befalls the sons of the earth. Man did not weave the web of life; he is merely a strand in it. Whatever he does to the web, he does to himself ..."-- Chief Seattle

The indigenous people’s understanding of and respect for Land is telling and timely

Photo: alternativedaily

'We become teachers for the reasons of the heart.

But many of us lose heart as time goes by.

How can we take heart, alone and together,

So we can give heart to our students and our world,

Which is what good teachers do?'-THE HEART OF A TEACHER

The Time is Now to Explore the Benefits of Nature-Based Education in Our Teaching Models

The current global pandemic crisis and more are the manifestation of the tragedy of separating ourselves from mother nature.

Covid-19 has come to tell us that we are not the kings of the world: It has exposed the great weakness within the human triumph

‘What a pity that we have not yet grasped this simple wisdom: Our Sacred Earth is the only Home We Have.’- Kamran Mofid

‘In all my academic life, spanning over four decades, I have been dismayed, frustrated and overwhelmed with pain to notice that our education model has not embraced the beauty and the wisdom of our mother nature and our sacred earth, corporating them into the teaching curriculum.

This, to my mind, has seriously deprived the students, our future leaders, or indeed, our current leaders, to get a wholesome, values-led education, and thus, has prevented them, to vision and implement policies to heal our world, to better our lives.’- Kamran Mofid

‘To transform our societies, our ways of living and working, to be in greater harmony with Nature, we need to listen to and learn from those who have maintained this harmony, often despite centuries of prejudice and repression...Our Solutions are in Nature. No one embodies this fact more than Indigenous peoples and local communities, who, through their deep connections with their territories, their world-views and ways of life, show us how to nurture life on Earth.’- Hannibal and The Gaia Team

In Praise of All that Matters

Photo: Pinterest

I Refuse to give up Hope: Earth Is A Mother that Never Dies- Kamran Mofid

Sacred Beauty, Sacred Wisdom, Sacred Earth: Celebrating an

Honouring Indigenous Knowledge for Future Generations

‘’We find security and reassurance in the predictable rhythms of nature.’

Photo:WallpaperSafari

‘We find security and reassurance in the predictable rhythms of nature.’

‘Predictable natural rhythms create a sense of security in all living creatures. The rhythms of the sun and the moon, the rhythms of sleeping and waking, the rhythms of our daily meals, and closer to home, the rhythm of our breathing and of our heart beating. As babies, these rhythms created a sense of safety, a sense of reassuring predictability within us. And remember that while in the womb, the rhythms of our mothers body were our universe of rhythm also; heard and felt deeply by us. The deep sense of comfort and security they gave us was carried through to after we were born, when, as babies, we would feel safest when close to our mother’s body, feeling the rise and fall of her breathing, the beat of her heart. The significance of this within our psyche cannot be overstated…’-The Importance of Attuning to Natural Rhythms

Connecting with the Earth's Natural Frequency

Photo:Brain World

‘More than 3.5 billion years ago, life first arrived on this planet, a planet that had a natural frequency. As life started to evolve, it did so surrounded by this frequency. So, unsurprisingly, it began tuning in. When human beings came to the Earth, an incredible relationship was sparked, a relationship that science is just beginning to understand. Do you feel generally happier and more peaceful when you’re out in nature, away from noise, traffic jams, and neon lights? It is not just that you left the city behind. Or that you’re a person who likes nature. In nature, your body more easily tunes into the Earth’s frequency and can restore, revitalize, and heal itself more effectively…’ Tuning in to the Earth’s Natural Rhythm

Land As Our Teacher

Today, we’re continuing our observation and thoughts on how to build a better world, how to nurture and nourish better life, a better relationship with all living things around us, by learning from the wisdom of indigenous knowledge, culture, spirituality and way of life and living.

To my mind, the first step to do so, must be to learn about their land-based education system and philosophy. This is the key to unlocking the door to a better world and harmonious living.

To begin this journey of discovery, I wish to draw your attention to an excellent study and analysis in a recent publication by the Canadian Commission for UNESCO. This article explores how Indigenous knowledge comes from the land, situates humans within the wider Universe and is embedded in language, story and governance centred around respect, reciprocity, reverence, humility and responsibility. The best way to understand Indigenous land-based education is as a way of teaching and learning that has existed since the beginning of humans—and while it may not be new, the context we’re in is, and it is giving Indigenous land-based education an increasingly critical importance.

Now, let us explore further and read more from the article.

Land-Based Education

Ushering in and integrating indigenous worldviews into classrooms

Photo: Land Acknowledgements- Oregon State University

‘Land as teacher: understanding Indigenous land-based education’

By Canadian Commission for UNESCO

Indigenous land-based education has implications for science, culture, politics, language, environmental stewardship,

land rights, reconciliation—and the future of the planet.

As Chief Seattle(c. 1786 – June 7, 1866), a proponent of ecological responsibility and

respect of Native Americans' land rights, has wisely reminded us:

Photo:whitewolfpack.com

‘For anyone who seeks an understanding of what Indigenous land-based education is, it may be instructive to begin by grasping what it is not. If your mind went straight to “taking the classroom outside” or “outdoor education,” bingo: that’s what it’s not. Or at least, that’s not all it is—not by far. A multi-faceted concept, Indigenous land-based education doesn’t lend itself to simple one-sentence definitions, and does mean different things to different people. It brings together layered concepts like the importance of language and the geography of stories, cosmologies and world views, land protections and rights, relationality and accountability, a connection to reconciliation, and much more.

It can offer significant benefits to Indigenous people by providing culturally relevant education, promoting opportunities for inter-generational knowledge transfer, and creating safe spaces for healing and learning. And by changing the relationship that many non-Indigenous people have with the land, it has the potential to lead to a healthier Earth for all.

Dr. Amy Parent, Noxs Ts'aawit, is Nisga’a from the Nass Valley of northwestern British Columbia and describes herself as an uninvited guest to the territories of the Squamish, Tsleil-Waututh and Musqueam peoples. She is also an assistant professor in the Department of Educational Studies at the University of British Columbia. Indigenous land-based education, she says, is a process that centres respect, reciprocity, reverence, humility and responsibility as values connected to the land through Indigenous knowledges—a very different view from the Eurocentric mindset, which has long understood land as a resource and object to serve human uses, much to the detriment of our living world. By its very nature, Indigenous land-based education has the capacity to create transformational opportunities for all Canadians to learn about the many ways in which our education, economic, social and political systems reinforce colonialism.

Or to put it more simply, says Parent, it teaches us that land is not a resource. Rather, “she is a dearly beloved, revered relative who is in crisis right now.”

Dr. Alex Wilson, Opaskwayak Cree Nation, leads the Indigenous land-based graduate program at the University of Saskatchewan. Her view of Indigenous land-based education is relational and focuses on understanding how knowledge connects to and comes from land, including water, sky and everything connected to them.

“Indigenous land-based education is its own paradigm based on Indigenous worldviews and beliefs and the passing on of knowledge to one another and to the next generation,” she says. “It is also a form of understanding our place within, and our responsibility to, the wider universe.”

Outdoor ed—or basically just “doing activities outside”—is at one far end the land-based education spectrum (with the Indigenous component removed), says Wilson. However, while being outside is obviously essential to getting acquainted with the land, just going outside is not enough. From there, the spectrum widens to recognize the importance of teaching about the land to create global citizens who will care for the Earth. There is also a place on the spectrum for place-based education. But the latter is still mostly about location, not necessarily about the spiritual and cultural knowledge that has been part of it or created through it.

At the other end of the spectrum, where Indigenous land-based education is understood in terms of its deepest and most expansive potential and meaning, it gives context to the knowledges that arise from the land as well as from a specific nation, says Wilson. It encompasses the preservation of culture, language and philosophy, and addresses the ramifications of colonization and “epistemicide”—the severing of Indigenous knowledge systems as a consequence of policies designed to limit or cut off access to food, sacred places, culture and language.

Along those lines, Chris Googoo, a member of the We’koqma’q First Nation now living in Millbrook, Nova Scotia, points out that sometimes, even Elders don’t realize that their stories are teaching science. He says it’s important to recognize that colonization served to suppress this awareness.

“Whenever we wanted to share knowledge, if it went against certain values in the science world or in certain ideologies—Catholicism being the main one—our knowledge was considered a kind of blasphemy at the time,” he says. “We were either shunned or reprimanded somehow when we shared it, so our Elders have learned not to share their knowledge. What we are required to do now is to create a safe environment where people can not only heal from the journeys of their parents and grandparents, but where we can bring out those memories, those stories, that science that we have done research on for thousands of years in a living lab.”

The importance of language and stories

As chief operating officer of Ulnooweg, which offers economic and community development support in Atlantic Canada, Googoo works to exemplify the values of the people he represents by expressing them in ways of being and knowing, culture, traditions and language in every way in which Ulnooweg does business. He says regionality is a crucial feature of Indigenous land-based education.

“If somebody is out west, they can’t talk about our Indigenous knowledge in our own regions, and neither can we talk about theirs,” he says. “The Indigenous element of land-based knowledge is regional.”

Regionality ties into language and the geography of stories—a particular interest of Thomas Johnson, Executive Director of the Eskasoni Fish and Wildlife Commission in Nova Scotia and a member of the Eskasoni Mi’kmaw Language Initiative group. Johnson says authentic Indigenous land-based knowledge is embedded in language and in the stories that transfer knowledge passed down from our ancestors.

“Storytelling is an ancient technique used to retain information and an important part of Indigenous traditions,” he explains. “It’s important for us to talk about these stories of the ancient past that were meant to be told in the Indigenous language, because if we don’t, they will die.”

In a reflection paper he wrote for the Canadian Commission for UNESCO entitled The Geography of Stories, Johnson explains what happens when the links between culture, territory and language are lost. He describes Kluskap’s journey, a Mi’kmaq legend that recounts some of the travels of Kluskap, who has been considered a teacher of the Mi’kmaq people. While there are many versions of the stories, Johnson’s paper describes the Cape Breton version of Kluskap’s journey through the Bras d’Or Lake, a large inland sea in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia.

Howard Terpning - Storyteller (A Blackfoot elder tells a legend of his people.)

It is difficult to do justice to the story in a short summary. However, the long and short of it is that Kluskap has a series of adventures that result in either encounters with or the creation of a number of the landscape’s noteworthy features, such as a cave, a set of five small islands, a prominent stone on the shoreline and outcroppings of rocks. These were all given Mi’kmaq names connected to events in the story, such as Petawlutik (Table Rock), where Kluskap has their dinner, or Pli’kan (Cape Split), where Kluskap uses a paddle to dig out the channel that forms Minas Basin in the Bay of Fundy.

Johnson writes that even though the Mi’kmaw language was shaped and created by this landscape, many elders and others in the area today have never heard of some of the words from Kluskap’s stories. Being disconnected from the land has led to the loss of the language—when the connection to the land is what is actually required to maintain that reciprocal relationship and feeling of interconnectedness.

“Losing the majority of our speakers was a direct result of what happens when a disconnect occurs between the Indigenous language and the land,” says Johnson.

Indigenous land-based education aims to remedy this disconnect by reviving the reciprocal relationship between Indigenous people and the land. It also encompasses several kinds of learning—about the land, about the history of the land and about how First Nations as a group interacted with the land. In fact, Johnson says the concepts are so closely intertwined that at one time, there was no need to even call it education. “It was just a way of life,” he says. “You lived it on a daily basis. You didn’t even realize you were being educated. You were one with nature. There was a deep love and respect for nature and all that it had to offer.”

It’s political

Recognizing the connections between Indigenous land-based education and language is fundamental to understanding the concept, agrees Parent.

“We were put on a land that looked like us and given a language that sounds like the land, with the words to describe the land and all of its beings,” she says, honouring the late Woody Morrison of the Haida Peoples, who first expressed it that way. “Woody said every land has its own Magic. So if you have a name from that language, then the land and the trees know you by that name. A soul name is a name, and the wind carries it to the tops of the highest mountains and over the waters.”

As a result, she says, naming practices are indivisible from Indigenous land-based education; regionality -- what Parent refers to as “locality” is key.

Adding to the complexity, Indigenous land-based education is inseparable from what Parent calls “really uncomfortable conversations” about our entanglements as Canadians in colonial violence, environmental degradation, the dispossession of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral homelands and the perpetuation of cultural genocide. It invites us, she says, “into a process where we begin discussing and addressing questions of land reclamation, reparations, Indigenous sovereignty and jurisdiction (or Canadian sovereignty on Indigenous stolen lands) while supporting land-based practices that will sustain Mother Earth.”

This ties into language and place names, she adds. For example, in B.C., the majority of lands were never ceded, “yet the landscapes were violently remapped, redrawn and renamed to reflect new toponyms that upheld the glory of European empires and the so-called ‘good deeds’ of their patriarchal forefathers,” she notes. “These toponyms silence Indigenous land-based names and erase them from Canadian historical records, curricula and public memory, and they redefine the land through a Eurocentric lens as an object and a resource.”

In comparison, says Parent, Indigenous land names powerfully signify the continued presence and recognition of Indigenous laws, history, governance and sovereignty since time immemorial, in keeping with the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report, and the Commission’s Calls to Action, which emphasized that the state has an obligation to provide an education that supports Indigenous sovereignty.

‘Education will be a key tool in the fight against climate change in the coming years.’-Photo: Iberdrola

“And we know there is a strong connection between the re-establishment of Indigenous land-based names and the revitalization of Indigenous languages and culture.”

Kinship, land protection and responsibility

A major global benefit of Indigenous land-based education may be its potential to lead to better environmental protections by changing people’s relationships with the land—a development that could have important implications for a world that is struggling with climate change, biodiversity loss and significant, steadily worsening environmental degradation.

For example, Wilson believes land-based education is part of climate change education—and a necessary part of that is about relationality and accountability. “Land protection is just a huge, huge part of that,” she explains. “If you understand—through our kinship structures or the way the language is structured—that parts of the land or animals are literally related to you, then you have a different kind of relationship with the land: you have something more like a familial relationship, where protection is naturally a part of it. I think that's really important.”

Googoo adds that it’s about creating a feeling of harmony and a deep connection with the Earth—an ideology that goes beyond basic religion. “I’m talking about words like intuition, sixth sense, an intimate connection with Mother Earth—it’s ‘up here’ where you can’t even really understand it, because it’s hard to understand a thousand years of scientific method.”

The reconciliation connection

Googoo ties reconciliation into these ideas using the example of going out into a forest and hugging a tree: a full understanding of the experience requires both western and Indigenous knowledge.

“You’ll feel the tree’s energy, there are chemical and electrical reactions that occur and connect us to it. We see it, and we have proven it scientifically. That’s two-eyed seeing, for me,” he says, referring to Etuaptmumk, the Mi’kmaq idea of looking at things from two different perspectives and trying to reach a common ground.

“And I think that’s a validation of both sides—that science validates Indigenous knowledge and Indigenous knowledge validates science. I believe that’s where true reconciliation occurs: when one respects the other’s knowledge. We have lots of theories that aren’t accepted yet, but it’s getting to a point where we are being asked to bring Indigenous knowledge into the public education system.”

Land-based education supports reconciliation by breathing new life into languages and cultures at risk of disappearing, teaching students about the history of residential schools, empowering them to develop their own connections to the land, and giving them the tools to protect and fight for it. It is a chance for Indigenous people to “reclaim and regain” their traditional territories just by being outside, says Googoo.

“It’s sort of like you’re planting a flag, but you’re actually planting a tree and giving back what Mother Nature had put there in the first place. This feeds into our narrative about the need to respect the treaties and traditional territories, not only in Atlantic Canada but elsewhere. It allows so much opportunity to teach not only Indigenous people, but non-Indigenous people about treaty relations and allyship.”

While reconciliation is primarily a settler responsibility, Indigenous efforts supporting decolonization necessarily challenge the dominance of Western thought, including about land. Colonization, says Wilson, imposed binaries that must be dismantled for progress to continue. She teaches a course called Queering Land-Based Education at the University of Saskatchewan that addresses these ideas, which she says arose when, in her research and teaching experiences, she began to identify patterns where people were simply recreating colonial constructs (but outdoors) in their land-based practices. She realized there was a need to examine and understand how land-based education could address the binaries imposed by colonization.

“That’s where queering comes in,” she says. “Not so much in terms of being inclusive of LGBTQ2S+ people, although that’s a part of it, but also understanding that because there’s such diversity in nature, that for any kind of binary that exists in humans’ minds, you can probably find something in nature that undoes it—or ‘queers’ it. I use the term queering rather than decolonizing because it centres a positive—like queering—rather than centring colonization and trying to undo it. This approach is generative, regenerative and life-giving rather than life-taking.”

Looking to the future

Although land-based education is not uniformly on offer at school boards across Canada yet, particularly in urban settings, interest in it is growing and spreading. Wilson says many school divisions—particularly in the Northwest Territories and northern Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta—have begun offering it in various forms. There are many examples of individual schools or entire systems that centre land-based knowledge as their core curriculum.

Indigenous land-based education holds the potential to create a new generation of Canadian citizens that have never been seen before by immersing them in a respect-based worldview of the land from their earliest days. It’s a positive example of what the future may hold as we try to tackle complex global environmental challenges.

Recently, Parent—in her role as a faculty co-director of the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw M.Ed. program—had a chance to work with several Sḵwx̱wú7mesh leaders who were instrumental in creating Aya7ayulh Chet (Cultural Journeys), a kindergarten-to-grade-6 program built around Indigenous land-based education in Squamish, B.C. The program is the outcome of a collaboration between the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation, the Sea-to-Sky School District and the Stawamus Elementary School parent advisory council. In addition to supporting land-based educational practices in the Skwxwú7mesh language, the school welcomes non-Indigenous students.

“We are creating citizens of Canada to be like no others before them,” says Joy Joseph-McCullough, associate education director for the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation, who was instrumental in developing Aya7ayulh Chet (Cultural Journeys). “The students will have an understanding and empathy that they will hold in their minds and hearts due to the spiritual and cultural teachings they are learning through the land. They will have a new lens. Imagine if one of them gets into politics and becomes a prime minister of Canada?”

Recounting a story about a little red-haired boy with freckles who was in the program, Joseph-McCullough describes a phone call the cultural teacher, Charlene Williams, received from the boy’s mother one day. Her son had been explaining that “in our Sḵwx̱wú7mesh way, this is how we do things, Mom.” The mother was concerned because in her mind, her son was not Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, but was speaking as though he was.

“She said, ‘I don’t know how to tell my son he is not Sḵwx̱wú7mesh.’”

Joseph-McCullough was adamant about supporting the parent because she knew land-based education was new. She recalls advising the family: "Culture is what you practice, and he is practicing our Sḵwx̱wú7mesh ways, so this has become his culture. We don’t have to take this from him. He can work through this, and figure it out as he grows older.”

Later, the mom called again because the young boy was so drawn to the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh ways that all he wanted for Christmas was a woven cedar basket.

“She asked one of my staff to teach her, so she could give her son what he wanted for Christmas,” Joseph-McCullough says.

Ultimately, says Wilson, the best way to understand Indigenous land-based education is as a way of teaching and learning that has existed since the beginning of humans—and while it may not be new, the context we’re in is, and it is giving Indigenous land-based education an increasingly critical importance.

“We’re at a place and time where we have an opportunity to draw from that knowledge,” she says. “If people had listened to Inuit people 60 years ago when they started sounding the alarm about climate change, what might be different now?”- Read the original article HERE

See also:

The Land is the Teacher: Watch it online

Humanity’s Attachment to Mother Earth

The Tuawhenua explain their attachment to the land

INDIGENOUS LAND-BASED LEARNING: A WAY TO TAKE ACTION ON CLIMATE CHANGE

How can environmental education help to combat climate change?

LAND AND SEA NETWORK (The series documents the lives of Canadians who live on the natural resources of the eastern coast of the country. They are the stories of people who keep the oldest traditions alive.)

......

A Selection of Related postings from our archive

'Be in love with life and the living and the world will be a better place.'- Kamran Mofid

The Tree of Wisdom, Old whimsical tree in the Wicklow forest, Ireland.-

Photo by Jenny Rainbow: fineartamerica.com

The Wisdom of Mother Nature belongs to all Life.

Let be guided and inspired by Her and Save the Web of Life

'Be like the sun for grace and mercy.

Be like the night to cover others’ faults.

Be like running water for generosity.

Be like death for rage and anger.

Be like the Earth for modesty.

Appear as you are.

Be as you appear.'- Rumi

On the 250th Birthday of William Wordsworth Let Nature be our Wisest Teacher

Climate Change, Environmental Degradation and the Rise of COVID-19

Detaching Nature from Economics is ‘Burning the Library of Life’

The IPCC Report- I Refuse to give up Hope: Earth Is A Mother that Never Dies

Today is Earth Overshoot Day 2021: We have exhausted and plundered our Mother Earth

Do we love the world enough to look after it, to save it?

We need to come together to stop the plunder of the commons

‘Nature and Me’: ‘Nature as a Cure for the Sickness of Modern Times’

‘Nature and Me’: ‘200 words to protect the planet’

'Nature and Me': Educating the Heart and the Soul of Children to Build a Better World

'Nature and Me': Unlocking a New Vision for a Better World

‘Nature and Me’: A Beautiful and Inspiring Path to repair our relationship with life

Embrace the Spirituality of the Autumn Equinox and Discover What it Means to be Human

Detaching Nature from Economics is ‘Burning the Library of Life’

By Forgetting Mother Nature- We have Now Ended Up with This unenviable World

The future that awaits the human venture: A Story from a Wise and Loving Teacher

The healing power of ‘Dawn’ at this time of coronavirus crisis

Coronavirus and the New Tapestry of Life: The time is now to rediscover our true selves

Are you physically and emotionally drained? I know of a good and cost-free solution!