- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 2374

‘The philosopher Adam Smith wasn't the free-market fundamentalist many assume he was. It's time we started reading him properly.’-Amartya Sen

...They have not, and thus, have set the world on fire!

This is the Book that the economists by and large have never read

And this is why, by and large, the discipline is in such a mess, discredited and is not trusted

If they had, then they would, among other issues, would have discovered ‘the appreciation of the demands of rationality, the need for recognising the plurality of human motivations, the connections between ethics and economics, and the codependent rather than free-standing role of institutions in general, and free markets in particular, in the functioning of the economy.’

And moreover, if they had, then, they would have accepted the £1000,000 Donation!!

Ethics boys

'Sir, Around 1991 I offered the London School of Economics a grant of £1 million to set up a Chair in Business Ethics. John Ashworth, at that time the Director of the LSE, encouraged the idea but had to write to me to say, regretfully, that the faculty had rejected the offer as it saw no correlation between ethics and economics. Quite.' Lord Kalms, House of Lords, in a letter to the Times (08/03/2011)

A forgotten book by one of history’s greatest thinkers reveals the surprising connections between economics, virtues, progress, fame, fortune, happiness and joy.

‘The Theory of Moral Sentiments is a global manifesto of profound significance to the interdependent world in which we live.’- Amartya Sen

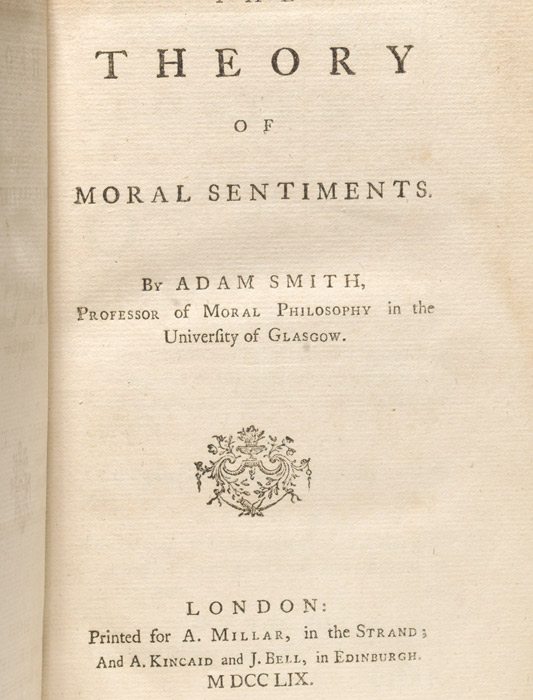

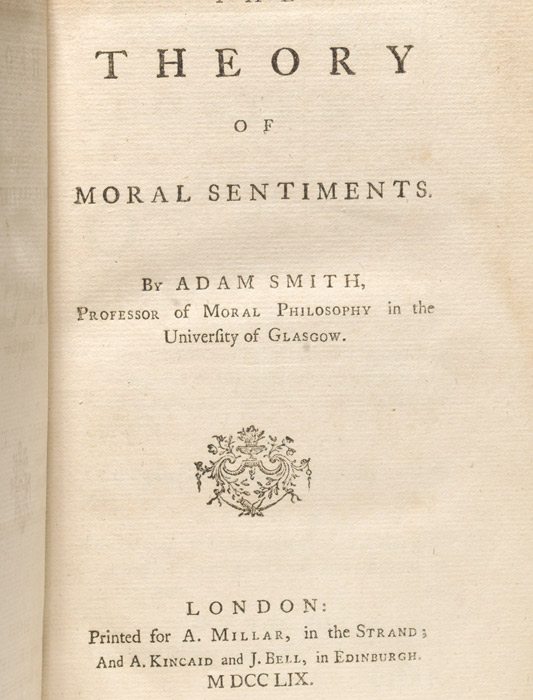

SMITH, Adam. The Theory of Moral Sentiments. London: Printed for A. Millar, in the Strand; And A. Kincaid and J. Bell, in Edinburgh, 1759.-Photo:baumanrarebooks.com

Nota bene

Where does my economic thinking come from? Who inspires me to say what I say? My economic guru is the real Adam Smith, not the false one taught at universities the world over. Let me explain:

‘As many observers, including some honest economists themselves have noted, the economics profession was arguably the first casualty of the 2008-2009 global financial crises. After all, its practitioners failed to anticipate the calamity, and many appeared unable to say anything useful when the time came to formulate a response.

Mainstream economic models were discredited by the crisis because they simply did not admit of its possibility. Moreover, training that prioritised technique over intuition and theoretical elegance over real-world relevance did not prepare economists to provide the kind of practical policy advice needed in exceptional circumstances.

Some argue that the solution is to return to the simpler economic models of the past, which yielded policy prescriptions that evidently sufficed to prevent comparable crises. Others insist that, on the contrary, effective policies today require increasingly complex models that can more fully capture the chaotic dynamics of the twenty-first-century economy.

Why this debate misses the key point. Because, it was not, and it is not about the models to begin with. It is all about what economics was and what it has become. It is all about the missing values in the so-called modern economics.

As a “Recovered” economist, who has seen the “Light” and hopefully is now wiser than before, I believe I can shed some light on this matter:

‘These days I am inspired by the “Real” and “True” Adam Smith, known the world over as the Father of New Economics. We should recall the wisdom of Adam Smith, who was a great moral philosopher first and foremost. In 1759, sixteen years before his famous Wealth of Nations, he published The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which explored the self-interested nature of man and his ability nevertheless to make moral decisions based on factors other than selfishness. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith laid the early groundwork for economic analysis, but he embedded it in a broader discussion of social justice and the role of government. Today we mainly know only of his analogy of the ‘invisible hand’ and refer to him as defending free markets; whilst ignoring his insight that the pursuit of wealth should not take precedence over social and moral obligations.

We are taught that the free market as a ‘way of life’ appealed to Adam Smith but not that he thought the morality of the market could not be a substitute for morality for society at large. He neither envisioned nor prescribed a capitalist society, but rather a ‘capitalist economy within society, a society held together by communities of non-capitalist and non-market morality’. As it has been noted, morality for Smith included neighbourly love, an obligation to practice justice, a norm of financial support for the government ‘in proportion to [one’s] revenue’, and a tendency in human nature to derive pleasure from the good fortune and happiness of other people.

He observed that lasting happiness is found in tranquillity as opposed to consumption. In their quest for more consumption, people have forgotten about the three virtues Smith observed that best provide for a tranquil lifestyle and overall social well-being: justice, beneficence (the doing of good; active goodness or kindness; charity) and prudence (provident care in the management of resources; economy; frugality).

I am very sorry that, no one taught me these when I was a student of economics, and then, I did not tell the truth about Adam Smith to my students when I became an economics lecturer; something that I very much regret and something that am trying hard to rectify, now that I am a “Recovering and Repenting” economist for the common good. At the end of the day, it is our honesty, humility and our struggle to seek the truth that will set us free and allow us to hold our head high.’...Economics, Globalisation and the Common Good: A Lecture at London School of Economics

Imaging a Better World: Moving forward with the real Adam Smith

Adam Smith and the Pursuit of Happiness

Adam Smith: Architect of the modern world

Re-examining the Relationship Between Ethics and Economics

Photo: trillfilm.com

The 18th-century philosopher Adam Smith wasn’t the free-market fundamentalist he is thought to be!

‘...that there are good ethical and practical grounds for encouraging motives other than self-interest.’- Adam Smith

The economist manifesto

A Reflection by Amartya Sen*

‘The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Adam Smith's first book, was published in early 1759. Smith, then a young professor at the University of Glasgow, had some understandable anxiety about the public reception of the book, which was based on his quite progressive lectures. On 12 April, Smith heard from his friend David Hume in London about how the book was doing. If Smith was, Hume told him, prepared for "the worst", then he must now be given "the melancholy news" that unfortunately "the public seem disposed to applaud [your book] extremely". "It was looked for by the foolish people with some impatience; and the mob of literati are beginning already to be very loud in its praises." This light-hearted intimation of the early success of Smith's first book was followed by serious critical acclaim for what is one of the truly outstanding books in the intellectual history of the world.

After its immediate success, Moral Sentiments went into something of an eclipse from the beginning of the 19th century, and Smith was increasingly seen almost exclusively as the author of his second book, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, which, published in 1776, transformed the subject of economics. The neglect of Moral Sentiments, which lasted through the 19th and 20th centuries, has had two rather unfortunate effects.

First, even though Smith was in many ways the pioneering analyst of the need for impartiality and universality in ethics (Moral Sentimentspreceded the better-known and much more influential contributions of Immanuel Kant, who refers to Smith generously), he has been fairly comprehensively ignored in contemporary ethics and philosophy.

Second, since the ideas presented in The Wealth of Nations have been interpreted largely without reference to the framework already developed in Moral Sentiments (on which Smith draws substantially in the later book), the typical understanding of The Wealth of Nations has been constrained, to the detriment of economics as a subject. The neglect applies, among other issues, to the appreciation of the demands of rationality, the need for recognising the plurality of human motivations, the connections between ethics and economics, and the codependent rather than free-standing role of institutions in general, and free markets in particular, in the functioning of the economy.

Beyond self-love

Smith discussed that to explain the motivation for economic exchange in the market, we do not have to invoke any objective other than the pursuit of self-interest. In the most widely quoted passage from The Wealth of Nations, he wrote: "It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love." In the tradition of interpreting Smith as the guru of selfishness or self-love (as he often called it, not with great admiration), the reading of his writings does not seem to go much beyond those few lines, even though that discussion is addressed only to one very specific issue, namely exchange (rather than distribution or production) and, in particular, the motivation underlying exchange. In the rest of Smith's writings, there are extensive discussions of the role of other motivations that influence human action and behaviour.

Beyond self-love, Smith discussed how the functioning of the economic system in general, and of the market in particular, can be helped enormously by other motives. There are two distinct propositions here. The first is one of epistemology, concerning the fact that human beings are not guided only by self-gain or even prudence. The second is one of practical reason, involving the claim that there are good ethical and practical grounds for encouraging motives other than self-interest, whether in the crude form of self-love or in the refined form of prudence. Indeed, Smith argues that while “prudence” was “of all virtues that which is most helpful to the individual”, “humanity, justice, generosity, and public spirit, are the qualities most useful to others”. These are two distinct points, and, unfortunately, a big part of modern economics gets both of them wrong in interpreting Smith.

The nature of the present economic crisis illustrates very clearly the need for departures from unmitigated and unrestrained self-seeking in order to have a decent society. Even John McCain, the Republican candidate in the 2008 US presidential election, complained constantly in his campaign speeches of “the greed of Wall Street”. Smith had a diagnosis for this: he called such promoters of excessive risk in search of profits “prodigals and projectors” - which, by the way, is quite a good description of many of the entrepreneurs of credit swap insurances and sub-prime mortgages in the recent past.

The term "projector" is used by Smith not in the neutral sense of "one who forms a project", but in the pejorative sense, apparently common from 1616 (or so I gather from The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary), meaning, among other things, "a promoter of bubble companies; a speculator; a cheat". Indeed, Jonathan Swift's unflattering portrait of "projectors" in Gulliver's Travels, published in 1726 (50 years before The Wealth of Nations), corresponds closely to what Smith seems to have had in mind. Relying entirely on an unregulated market economy can result in a dire predicament in which, as Smith writes, "a great part of the capital of the country" is "kept out of the hands which were most likely to make a profitable and advantageous use of it, and thrown into those which were most likely to waste and destroy it".

False diagnoses

The spirited attempt to see Smith as an advocate of pure capitalism, with complete reliance on the market mechanism guided by pure profit motive, is altogether misconceived. Smith never used the term “capitalism” (I have certainly not found an instance). More importantly, he was not aiming to be the great champion of the profit-based market mechanism, nor was he arguing against the importance of economic institutions other than the markets.

Smith was convinced of the necessity of a well-functioning market economy, but not of its sufficiency. He argued powerfully against many false diagnoses of the terrible “commissions” of the market economy, and yet nowhere did he deny that the market economy yields important “omissions”. He rejected market-excluding interventions, but not market-including interventions aimed at doing those important things that the market may leave undone.

Smith saw the task of political economy as the pursuit of “two distinct objects”: “first, to provide a plentiful revenue or subsistence for the people, or more properly to enable them to provide such a revenue or subsistence for themselves; and second, to supply the state or commonwealth with a revenue sufficient for the public services”. He defended such public services as free education and poverty relief, while demanding greater freedom for the indigent who receives support than the rather punitive Poor Laws of his day permitted. Beyond his attention to the components and responsibilities of a well-functioning market system (such as the role of accountability and trust), he was deeply concerned about the inequality and poverty that might remain in an otherwise successful market economy. Even in dealing with regulations that restrain the markets, Smith additionally acknowledged the importance of interventions on behalf of the poor and the underdogs of society. At one stage, he gives a formula of disarming simplicity: “When the regulation, therefore, is in favour of the workmen, it is always just and equitable; but it is sometimes otherwise when in favour of the masters.” Smith was both a proponent of a plural institutional structure and a champion of social values that transcend the profit motive, in principle as well as in actual reach.

Smith’s personal sentiments are also relevant here. He argued that our “first perceptions” of right and wrong “cannot be the object of reason, but of immediate sense and feeling”. Even though our first perceptions may change in response to critical examination (as Smith also noted), these perceptions can still give us interesting clues about our inclinations and emotional predispositions.

One of the striking features of Smith's personality is his inclination to be as inclusive as possible, not only locally but also globally. He does acknowledge that we may have special obligations to our neighbours, but the reach of our concern must ultimately transcend that confinement. To this I want to add the understanding that Smith's ethical inclusiveness is matched by a strong inclination to see people everywhere as being essentially similar. There is something quite remarkable in the ease with which Smith rides over barriers of class, gender, race and nationality to see human beings with a presumed equality of potential, and without any innate difference in talents and abilities.

He emphasised the class-related neglect of human talents through the lack of education and the unimaginative nature of the work that many members of the working classes are forced to do by economic circumstances. Class divisions, Smith argued, reflect this inequality of opportunity, rather than indicating differences of inborn talents and abilities.

Global reach

The presumption of the similarity of intrinsic talents is accepted by Smith not only within nations but also across the boundaries of states and cultures, as is clear from what he says in both Moral Sentiments and The Wealth of Nations. The assumption that people of certain races or regions were inferior, which had quite a hold on the minds of many of his contemporaries, is completely absent from Smith's writings. And he does not address these points only abstractly. For example, he discusses why he thinks Chinese and Indian producers do not differ in terms of productive ability from Europeans, even though their institutions may hinder them.

He is inclined to see the relative backwardness of African economic progress in terms of the continent’s geographical disadvantages - it has nothing like the “gulfs of Arabia, Persia, India, Bengal, and Siam, in Asia” that provide opportunities for trade with other people. At one stage, Smith bursts into undisguised wrath: “There is not a negro from the coast of Africa who does not, in this respect, possess a degree of magnanimity which the soul of his sordid master is too often scarce capable of conceiving.”

The global reach of Smith’s moral and political reasoning is quite a distinctive feature of his thought, but it is strongly supplemented by his belief that all human beings are born with similar potential and, most importantly for policymaking, that the inequalities in the world reflect socially generated, rather than natural, disparities.

There is a vision here that has a remarkably current ring. The continuing global relevance of Smith's ideas is quite astonishing, and it is a tribute to the power of his mind that this global vision is so forcefully presented by someone who, a quarter of a millennium ago, lived most of his life in considerable seclusion in a tiny coastal Scottish town. Smith's analyses and explorations are of critical importance for any society in the world in which issues of morals, politics and economics receive attention. The Theory of Moral Sentiments is a global manifesto of profound significance to the interdependent world in which we live.’- Amartya Sen, The economist manifesto

Read More:

A Must Read Book about how Adam Smith can change your life for better

My Economics and Business Educators’ Oath: My Promise to My Students

The Age Of Perpetual Crisis: What are we to do in a world seemingly spinning out of our control?

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 3079

ABOUT HOW ADAM SMITH CAN CHANGE YOUR LIFE

‘Adam Smith may have become the patron saint of capitalism after he penned his most famous work, The Wealth of Nations. But few people know that when it came to the behavior of individuals—the way we perceive ourselves, the way we treat others, and the decisions we make in pursuit of happiness—the Scottish philosopher had just as much to say. He developed his ideas on human nature in an epic, sprawling work titled The Theory of Moral Sentiments.

Most economists have never read it, and for most of his life, Russ Roberts was no exception. But when he finally picked up the book by the founder of his field, he realized he’d stumbled upon what might be the greatest self-help book that almost no one has read.

In How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life, Roberts examines Smith’s forgotten masterpiece, and finds a treasure trove of timeless, practical wisdom. Smith’s insights into human nature are just as relevant today as they were three hundred years ago. What does it take to be truly happy? Should we pursue fame and fortune or the respect of our friends and family? How can we make the world a better place? Smith’s unexpected answers, framed within the rich context of current events, literature, history, and pop culture, are at once profound, counterintuitive, and highly entertaining.’- See more and purchase the book

This is the Book that the economists by and large have never read

And this is why, by and large, the discipline is in such a mess and is not trusted

A forgotten book by one of history’s greatest thinkers reveals the surprising connections between happiness, virtue, fame, and fortune

SMITH, Adam. The Theory of Moral Sentiments. London: Printed for A. Millar, in the Strand; And A. Kincaid and J. Bell, in Edinburgh, 1759.-Photo:baumanrarebooks.com

‘Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments laid the foundation on which The Wealth of Nations was later to be built and proposed the theory which would be repeated in the later work: that self-seeking men are often “led by an invisible hand… without knowing it, without intending it, to advance the interests of the society.” “The fruit of his Glasgow years… The Theory of Moral Sentiments would be enough to assure the author a respected place among Scottish moral philosophers, and Smith himself ranked it above the Wealth of Nations…. Its central idea is the concept, closely related to conscience, of the impartial spectator who helps man to distinguish right from wrong. For the same purpose, Immanuel Kant invented the categorical imperative and Sigmund Freud the superego” (Niehans, 62). With Moral Sentiments and Wealth of Nations Smith created “not merely a treatise on moral philosophy and a treatise on economics, but a complete moral and political philosophy, in which the two elements of history and theory were to be closely conjoined” (Palgrave III, 412-13). To Smith when man pursues “his own private interests, the original and selfish sentiments of Theory of Moral Sentiments, he will, in the economic realm, choose those endeavors which will best serve society. Herein lies the connection between the two great works which make them the work of a single and largely consistent theorist” (Paul, “Adam Smith,” 293).

In his Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith develops an ethics based on a “unifying principle—in this case, of sympathy—which would shed light on the harmonious and beneficial order of the moral world. As such it was of considerable interest to Smith’s contemporaries who were groping for an ethics that would flow from man’s impulses or sentiments rather than from his reason, from ‘innate ideas,’ or from theological precepts. If Smith had written only The Theory of Moral Sentiments, he would enjoy in the philosophers hall of fame a niche not unlike that reserved for Shaftesbury or Hutcheson.” Both Moral Sentiments and Wealth of Nations reflect Smith’s “attempt to anchor the new science of political economy in a Newtonian universe, mechanical albeit harmonious and beneficial, in which society is shown to benefit from the unintended consequences of the pursuit of individual self-interest. There is thus a considerable affinity between the structure of The Theory of Moral Sentiments and that of The Wealth of Nations. Each work is integrated by a great unifying principle. What sympathy accomplishes in the moral world, self-interest does in the economic one. Either principle, in its respective realm, is shown to produce a harmony such as the one that characterizes Newton’s order of nature… Smith’s ethics is one of self-command or self-reliance, just as is his laissez faire economics…. Smith’s ethics and his economics are integrated by the same principle of self-command, or self-reliance, which manifests itself in economics in laissez faire” (Spiegel, Growth of Economic Thought, 229-231)’.-Bauman Rare Books

Nota bene

Where does my economic thinking come from? Who inspires me to say what I say? My economic guru is the real Adam Smith, not the false one taught at universities the world over. Let me explain:

‘As many observers, including some honest economists themselves have noted, the economics profession was arguably the first casualty of the 2008-2009 global financial crises. After all, its practitioners failed to anticipate the calamity, and many appeared unable to say anything useful when the time came to formulate a response.

Mainstream economic models were discredited by the crisis because they simply did not admit of its possibility. Moreover, training that prioritised technique over intuition and theoretical elegance over real-world relevance did not prepare economists to provide the kind of practical policy advice needed in exceptional circumstances.

Some argue that the solution is to return to the simpler economic models of the past, which yielded policy prescriptions that evidently sufficed to prevent comparable crises. Others insist that, on the contrary, effective policies today require increasingly complex models that can more fully capture the chaotic dynamics of the twenty-first-century economy.

Why this debate misses the key point. Because, it was not, and it is not about the models to begin with. It is all about what economics was and what it has become. It is all about the missing values in the so-called modern economics.

As a “Recovered” economist, who has seen the “Light” and hopefully is now wiser than before, I believe I can shed some light on this matter.

‘These days I am inspired by the “Real” and “True” Adam Smith, known the world over as the Father of New Economics. We should recall the wisdom of Adam Smith, who was a great moral philosopher first and foremost. In 1759, sixteen years before his famous Wealth of Nations, he published The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which explored the self-interested nature of man and his ability nevertheless to make moral decisions based on factors other than selfishness. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith laid the early groundwork for economic analysis, but he embedded it in a broader discussion of social justice and the role of government. Today we mainly know only of his analogy of the ‘invisible hand’ and refer to him as defending free markets; whilst ignoring his insight that the pursuit of wealth should not take precedence over social and moral obligations.

We are taught that the free market as a ‘way of life’ appealed to Adam Smith but not that he thought the morality of the market could not be a substitute for morality for society at large. He neither envisioned nor prescribed a capitalist society, but rather a ‘capitalist economy within society, a society held together by communities of non-capitalist and non-market morality’. As it has been noted, morality for Smith included neighbourly love, an obligation to practice justice, a norm of financial support for the government ‘in proportion to [one’s] revenue’, and a tendency in human nature to derive pleasure from the good fortune and happiness of other people.

He observed that lasting happiness is found in tranquillity as opposed to consumption. In their quest for more consumption, people have forgotten about the three virtues Smith observed that best provide for a tranquil lifestyle and overall social well-being: justice, beneficence (the doing of good; active goodness or kindness; charity) and prudence (provident care in the management of resources; economy; frugality).

I am very sorry that, no one taught me these when I was a student of economics, and then, I did not tell the truth about Adam Smith to my students when I became an economics lecturer; something that I very much regret and something that am trying hard to rectify, now that I am a “Recovering and Repenting” economist for the common good. At the end of the day, it is our honesty, humility and our struggle to seek the truth that will set us free and allow us to hold our head high.’...Economics, Globalisation and the Common Good: A Lecture at London School of Economics

Imaging a Better World: Moving forward with the real Adam Smith

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 2898

Poverty, Destitution, Hunger and Homelessness in the Midst of Plenty

This is nothing, but a manifestation of a cruel and inhumane state of affairs

Homeless Children of ‘Great Britain’ growing up in Shipping Containers

Do you have an eye for justice and sense of duty? Then, these questions are for you

Photo:bbc.co.uk

This, surely, must be, a lasting shame and scar on the conscience of Britain

'In Britain, the government’s ideological austerity agenda has contributed to plunging 4.1 million children into poverty. This means insecure accommodation, cold homes and not enough to eat – and young people absorb all of this stress. The anxiety of living like this should not be underestimated as a factor in the rise of self-harm behaviours. Worries about exams, university applications and job prospects all loom large too, particularly in a world where employment options are too often limited and precarious.'

Nota bene

A journey through a land of austerity, poverty and inequality: Welcome to Britain

The pertinent question is:

Where has the nation’s moral compass gone? Where is the outrage, disgust, anger and indignation about this inhumanity and abuse?

- In Praise of Darwin Debunking the Self-seeking Economic Man

- American Dream was False and is Dead. But, the Good American Dream Can be Resurrected

- In Praise of Youth on International Youth Day- Monday 12 August 2019

- Dr. Larch Maxey, We Owe it to Our Humanity to hear you, to emulate you

- World in Chaos and Despair: The Healing Power of Slow Food