- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 2346

On and On How Fragile We Are...

Life is so full of unpredictable beauty and strange surprises

Photo:bing.com

As many people, wiser than me have noted, our lives and the world in which we all live, are so unpredictable. Things happen suddenly, unexpectedly. We want to feel we are in control of our own existence. In some ways we are, in some ways we're not ... Life, it can bring you so much joy and yet at the same time cause so much pain.

'A Short History of Falling – like The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, and When Breath Becomes Air – is a searingly beautiful, profound and unforgettable memoir that finds light and even humour in the darkest of places.'

In this world, as it is today, it is humbling, a source of joy and hope, to have learnt about Joe Hammond, his life, journey and values.

'We keep an old shoebox, Gill and I, nestled in a drawer in our room. It’s filled with thirty-three birthday cards for our two young sons: one for every year I’ll miss until they’re twenty-one. I wrote them because, since the end of 2017, I’ve been living with – and dying from – motor neurone disease.

This book is about the process of saying goodbye. To my body, as I journey from unexpected clumsiness to a wheelchair that resembles a spacecraft, with rods and pads and dials and bleeps. To this world, as I play less of a part in it and find myself floating off into unlighted territory. To Gill, my wife. To Tom and Jimmy.'

Photo:amazon.com

A Book All About Celebration of Love, What is Important, What is Meaningful.

It is a book about human resilience in the face of great adversity. This is a truly beautiful book; Hammond never writes with a trace of self-pity or despair. He says that he wrote the book for his sons but, along the way, he appears to have laid to rest a few ghosts of his own.

A Short History of Falling: Everything I Observed About Love Whilst Dying

‘A Short History of Falling is about the sadness (and the anger, and the fear), but it’s about what’s beautiful too. It’s about love and fatherhood, about the precious experience of observing my last moments with this body, surrounded by the people who matter most. It’s about what it feels like to confront the fact that my family will persist through time with only a memory of me. In many ways, it has been the most amazing time of my life.’

Joe Hammond’s memoir A Short History of Falling: Everything I Observed About Love Whilst Dying is a poignant glimpse into a life with motor neurone disease.

Celebrating the courageous and loving life of Joe Hammond who passed away, aged 50, on 30 November 2019. He is survived by his wife Gill, and their two sons, seven-year-old Tom and three-year-old Jimmy.

Joe Hammond (right) pictured in 2018 with his wife Gill, and sons Tom and Jimmy. Photo: Harry Borden/The Guardian

Joe Hammond's unexpectedly uplifting book about life with a terminal illness

Joe’s raw and honest depiction of his condition will leave you with a new-found wonder for the human body, for life, love, living and dying

In the book, we follow Joe from that fateful day in a hospital in Portugal, when he first learned of his diagnosis, through to his family’s move back to the UK, the installation of medical equipment in his home and undignified situations on the hospital commode.

His memoir is brimming with contemplative musings on the nature of life and our relationship with our bodies.

‘As I get weaker, less a part of this world, or less a part of what I love, less a part of my family’s life, I can perceive its edges with fantastic clarity. I can lie against it, lolling my arms over the edge, running my fingers around the rim.’

Helen Garnons-Williams, his editor, described Hammond as a remarkable person. “It is our great honour – and pleasure – to have been his publisher,” she added. “His memoir is a lasting legacy: a book of consolation, wisdom, and – most astonishingly – wonder. Above all, it’s a celebration of love. Joe was hugely loved, and will be hugely missed.”*

Will Francis, Hammond’s literary agent, said: “Joe’s mind only seemed to become sharper as his disease progressed ... I hope Gill, Tom and Jimmy will draw comfort from the book he left, which is full of both his wit and his love for them. He was a deeply original writer who used his own mortality as a lens, to see familiar things anew.”*

‘It feels like a frustration with the idea that things happen: the idea that we all might grow old or that any of us might contract an illness or disease and not be able to do anything about it, or the idea that none of us really possess control over our lives.’

However, the book remains uplifting, even at its most tragic moments.

‘I have all these losses, and feel a kind of freedom in that. With each awkward, spasmodic movement, or the difficulty I have wiping my own bottom, or with the slur developing in my voice, the narcissist recedes. There’s nothing for him here. Not any more.’

The memoir closes with Joe, sat in his wheelchair, watching his two sons playing in the distance.

Tom, Jimmy and Gill are lovingly observed throughout the book. Joe writes of the isolation he experiences, the distance his disease creates between him and his family.

Although, with his trademark levity, he finds a way to rise above those feelings and instead look hopefully to their future.

Joe playing with his two sons Tom and Jimmy (left) in the garden. Photo:mariecurie.org.uk

‘I know that one day there may be other important men in Tom and Jimmy’s life and it’s hard not knowing if these relationships will be OK. I just have to trust that they will be, which is another way of letting go and knowing that it’s never possible to have control; not really.’- Read more

*Joe Hammond, author of acclaimed motor neurone disease memoir, dies aged 50

Product description

A Short History of Falling – like The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, and When Breath Becomes Air – is a searingly beautiful, profound and unforgettable memoir that finds light and even humour in the darkest of places.

We keep an old shoebox, Gill and I, nestled in a drawer in our room. It’s filled with thirty-three birthday cards for our two young sons: one for every year I’ll miss until they’re twenty-one. I wrote them because, since the end of 2017, I’ve been living with – and dying from – motor neurone disease.

This book is about the process of saying goodbye. To my body, as I journey from unexpected clumsiness to a wheelchair that resembles a spacecraft, with rods and pads and dials and bleeps. To this world, as I play less of a part in it and find myself floating off into unlighted territory. To Gill, my wife. To Tom and Jimmy.

A Short History of Falling is about the sadness (and the anger, and the fear), but it’s about what’s beautiful too. It’s about love and fatherhood, about the precious experience of observing my last moments with this body, surrounded by the people who matter most. It’s about what it feels like to confront the fact that my family will persist through time with only a memory of me. In many ways, it has been the most amazing time of my life.

Review

‘it is Hammond’s curiosity about death and his desire to report from the front line that makes this such a strangely invigorating read…his testimony deserves a place on the shelf beside When Breath Becomes Air and Late Fragments’ Cathy Rentzenbrink, author of The Last Act of Love,The Times

‘A brave, stirring memoir of a man staring down the barrel of his own mortality’ Irish Times

‘At the end, what one feels is that this is a book to extend empathy, to ensure one understands what it is to have MND and to witness one man facing it with exceptional courage. It is also a moving reiteration that a “short” history is our human lot’ Observer

‘His voice is captivating, his observations are searing, and his book is a blessing. This book will inspire you even as it breaks your heart’ Kathryn Mannix, author of With the End in Mind

‘I loved this book, and read it in a day. It's surprising and uncommon and I don't think I'll ever forget it’ Sunjeev Sahota, author of The Year of the Runaways

'A Short History of Falling is a beautifully written reminder that life can be tragic as well as full of joy' Christie Watson, bestselling author of The Language of Kindness

‘Touching and tragic. It is very hard to imagine how anyone could write so lyrically,dispassionately and persuasively of their imminent demise and its effect on those around them’ James Le Fanu, author of Too Many Pills

'An inspirational, ultimately heartbreaking account of experiencing life as the nervous system fails, shared with courage and humour' Professor Stephen Westaby, author of Fragile Lives

‘You will cherish everyone and everything you love, not to mention the capabilities of your own body, all the more dearly after reading this beautiful, devastating and stunningly written memoir’ Caroline Sanderson, Bookseller Book of the Month

About the Author

Joe Hammond was a critically acclaimed writer and playwright. He took part in the Royal Court Studio Writers' Group in 2012, having previously been mentored by the theatre and BBC. His debut London production 'Where the Mangrove Grows' played at Theatre503 in 2012 and was later published by Bloomsbury. His memoir, A Short History of Falling, chronicling the last days of his life, was published by 4th Estate in 2019 shortly before his death. He is survived by his wife and two sons.

Joe Hammond's final article: ‘I’ve been saying goodbye to my family for two years’

Last year the author wrote about parenting with motor neurone disease. Here, he reflects on the end of life, before his death two weeks ago

'In the beginning I was just a dad who fell over a bit and then couldn’t drive the car. Then we had a name for what was happening to me: motor neurone disease. The rest of my physical decline has taken two years and I now write with a camera attached to a computer, which tracks reflections from my pupils. I can use the same device to talk with my synthetic voice. It’s obviously slower to use, and has trained me to get to the point, in much the same way that dying has.

In the room next door, as I write, I can hear Jimmy, my two-year-old son, offering to take passengers on a bus ride to various destinations. It’s half-term and Tom, my seven-year-old, has wandered out into the garden. He’s smiling, looking back at the house, as he points out a squirrel to someone standing inside. There’s adult laughter, too. I can hear Gill, my wife, talking with one of my carers.'...Continue to read

...And now we will be most grateful if you would kindly consider supporting the GCGI Christmas Appeal 2019

Having a member of the family diagnosed with motor neurone disease (MND) is absolutely devastating for anyone, the patients, themselves, their families, but it can be particularly tough for children who are still developing emotionally.

This Christmas, many families will be struggling to make sense of this and other traumatic/terminal illnesses. The journey is painful and at times must be unbearable.

This is why the GCGI has chosen the following two charities for its Christmas appeal 2019. The right care means everything to people living with a terminal illness and their families. Please be an instrument of hope to all sufferers by giving to:

The Motor Neurone Disease Association

Care and support through terminal illness | Marie Curie

Our Christmas Message: A time to open our hearts

May you find joy in the simple pleasures of life and may the light of the holiday season fill your heart with the hope for a better world

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 3340

Turn the Strike to a Force for the Common Good

University staff across the UK are striking this week over pay, working conditions and pensions. Photo:theguardian.com

Nota bene

Neoliberalism has Eroded our Ability to Know What it Means to Be Human

Neoliberal Education: From Delusion to Destruction

Neoliberal University: A marketised and dehumanised place that has prioritised profit, upmarket student accommodation, super-duper gyms, and cafe-culture over good education and the welfare of staff and students.

The physical and emotional landscape of the university has fundamentally changed under neloliberal fundamentalism. The devastation wrought cannot be overstated in terms of reduced standards, entrenched inequality and the significant rise in mental, emotional and physical illness amongst all those working for universities.

So, Colleagues, Rise Up, and Make Your Strike Good for the Common Good

Fighting for the Heart and Soul of Public Higher Education

Photo:natidotezine.com

No more neoliberal teaching. No more neoliberal praising. No more neoliberal consulting and research! No more market knows best! No more neoliberal textbooks from the neoliberal editors and publishers. No more neoliberal bosses harassing the faculty into submission! No more neoliberal garbage at your university!

Only you can do that by joining me and many other concerned observers by reflecting upon and asking some timeless questions, questions of meaning and purpose:

What is Education? What is a University? What is Knowledge? What is Information? What is Wisdom? What is Teaching? What is Philosophy? What is Research? What is Success? What is Work? What is Vocation? What is Life? What is Spirituality? What is Kindness? What is Love? What is Humanity? What is Nature? What is Being? What is Home? What is the World?...What is to be Human?

Having done that, then, we, as values-led educators, will rise above the ignorance of the current neoliberal political economy which functions as a mechanism to farm humans and harvest the wealth they create.

This is the path to a valued education system and the creation of a world class university, which we all wish to be part of.

So, Colleagues, Universities must become places of hope for a better world by saying NO to the neoliberal fandangle!

So, Colleagues, Teach as if People, Humanity, Mother Earth and all the Web of Life Mattered

And publish your teaching oath and values, so that all know who you are and what you stand for

Stop the Neoliberal Attacks on You and Your University

‘There's a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can't take part! You can't even passively take part! And you've got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels ... upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you've got to make it stop! And you've got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you're free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!’- Mario Savio, the Berkeley Free Speech leader, addressing the students and faculty, in front of UC-Berkeley’s Sproul Hall, December 1964

Photo: truthout.org

This week’s pay, working conditions and pensions strike is important – but so is the impact of the inhumane neoliberalism and austerity on everything that was once good in the world, including education, universities, the entire aspect of learning experiences, and relationships.

Your strike, your fight for justice, should be extended to end this false socio- political and economic ideology and replace it with goodness, beauty, wisdom and kindness. In short, make education and universities, once again, for the common good.

Dear Colleagues,

As you begin your eight-day strike, you will know that many people across the country support your aims and wish you all success.

But colleagues, your struggles, your pain and agony will be in vain, if you do not do your utmost to destroy and dismantle the seeds of your pain, namely, the inhumane and false ideology of neoliberalism, that has given you the neoliberal university that now you feel so unfortunate and unhappy to work for.

Although many have sympathy for you and your cause, we must not forget that many in your ranks have been the cheerleaders for neoliberalism. Many in your ranks have been found guilty of causing, via your neoliberal teachings, the 2008 financial crash, with the ensuing inhumane and unjustifiable austerity, imposed on the 99% (Which ironically includes your good selves!) , by the neoliberal governments, with the heartless, vision-less, arrogant ministers and officials ‘educated’ at your universities!

Now that you, yourselves, have come to feel the pain, agony, and humiliation of neoliberalism and its consequences, please become an instrument of change, fight this cancerous and false ideology, change your neoliberal curriculum and make education, once again, values-led and for the common good.

Universities with your full support and moral force, must become a place of hope, kindness and happiness, so that, together with students, all can begin to reimagine a better world, to be designed and built by all the stakeholders.

If you need inspiration, I am more than happy to oblige! I started the struggle many years ago, and I will be delighted to share the experience and the journey. (See a few links below).

With my best wishes,

Kamran Mofid

For your reflection

The Value of Values: Why Values Matter

Photo: virtuesforlife.com

The phenomenon that pulls humanity together — Kindness

Kindness is What Makes Us Human- Lest We Forget

Neoliberal Education has Eroded Values of Kindness and Compassion.

As long as this inhumane and false ideology reins, we will not know what it means to be human.

The Neoliberal University: A House of Fear and an Anxiety Machine

Photo:hepi.ac.uk

Neoliberal university is the Road to Serfdom

Grand Heist: The Theft of the Century by the Most 'Educated Thieves'- All with MBAs and PhDs!

Neoliberalism destroys human potential and devastates values-led education

Recession, Austerity, Mental, Emotional and Physical Illness

Calling all academic economists: What are you teaching your students?

Coventry and I: The story of a boy from Iran who became a man in Coventry

‘Education of the mind without education of the heart is no education at all.’-Aristotle

“Don’t just teach your students how to count. Teach them what counts most.”

“The one continuing purpose of education, since ancient times, has been to bring people to as full realization as possible of what it is to be a human being.”-Arthur W. Foshay, author of ‘The Curriculum: Purpose, Substance and Practice’

Kindness University: The 'Antidote' to an Unkind World

What if Universities Taught KINDNESS?

Wouldn’t the world be a better place with a bit more kindness? Harnessing the Economics of Kindness

An Open Letter to University Leaders: Students’ Mental and Emotional Wellbeing Must Be Our Priority

Student Suicides at Bristol University: My Open Letter to the Vice-Chancellor, Prof. Hugh Brady

University students are crying out for mental health wellbeing modules

Neoliberalism and the rise in global loneliness, depression and suicide

The Journey to Sophia: Education for Wisdom

My Economics and Business Educators’ Oath: My Promise to My Students

What might an Economy for the Common Good look like?

The Age Of Perpetual Crisis: What are we to do in a world seemingly spinning out of our control?

Remaking Economics in an age of economic soul-searching

The World would be a Better Place if Economists had Read This Book

Britain today and the Bankruptcy of Ideas, Vision and Values-less Education

The Value of Values: Values-led Education to Make the World Great Again

For more reading see:

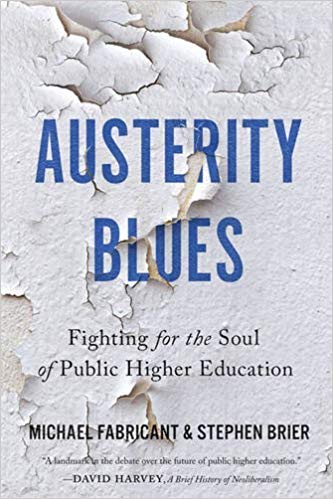

A Must Read Book

Austerity Blues: Fighting for the Soul of Public Higher Education

'Public higher education in the postwar era was a key economic and social driver in American life, making college available to millions of working men and women. Since the 1980s, however, government austerity policies and politics have severely reduced public investment in higher education, exacerbating inequality among poor and working-class students of color, as well as part-time faculty. In Austerity Blues, Michael Fabricant and Stephen Brier examine these devastating fiscal retrenchments nationally, focusing closely on New York and California, both of which were leaders in the historic expansion of public higher education in the postwar years and now are at the forefront of austerity measures.

Fabricant and Brier describe the extraordinary growth of public higher education after 1945, thanks largely to state investment, the alternative intellectual and political traditions that defined the 1960s, and the social and economic forces that produced austerity policies and inequality beginning in the late 1970s and 1980s. A provocative indictment of the negative impact neoliberal policies have visited on the public university, especially the growth of class, racial, and gender inequalities, Austerity Blues also analyzes the many changes currently sweeping public higher education, including the growing use of educational technology, online learning, and privatization, while exploring how these developments hurt students and teachers. In its final section, the book offers examples of oppositional and emancipatory struggles and practices that can help reimagine public higher education in the future.

The ways in which factors as diverse as online learning, privatization, and disinvestment cohere into a single powerful force driving deepening inequality is the central theme of the book. Incorporating the differing perspectives of students, faculty members, and administrators, the book reveals how public education has been redefined as a private benefit, often outsourced to for-profit vendors who "sell" education back to indebted undergraduates. Over the past twenty years, tuition and related student debt have climbed precipitously and degree completion rates have dropped. Not only has this new austerity threatened public universities’ ability to educate students, Fabricant and Brier argue, but it also threatens to undermine the very meaning and purpose of public higher education in offering poor and working-class students access to a quality education in a democracy. Synthesizing historical sources, social science research, and contemporary reportage, Austerity Blues will be of interest to readers concerned about rising inequality and the decline of public higher education.' Click here to buy the book

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 4126

Photo:The Pictures Quotes Blog

‘Education of the mind without education of the heart is no education at all.’-Aristotle

“The one continuing purpose of education, since ancient times, has been to bring people to as full realization as possible of what it is to be a human being.”-Arthur W. Foshay, author of ‘The Curriculum: Purpose, Substance and Practice’

Kindness University: The 'Antidote' to an Unkind World

Given the state of our world today: What if Universities have been Educating for compassion, empathy and kindness too?

Kindness and the Good Education

'Some say that my teaching is nonsense.

Others call it lofty but impractical.

But to those who have looked inside themselves,

this nonsense makes perfect sense.

And to those who put it into practice,

this loftiness has roots that go deep.

I have just three things to teach:

simplicity, patience, compassion.

These three are your greatest treasures.

Simple in actions and in thoughts,

you return to the source of being.

Patient with both friends and enemies,

you accord with the way things are.

Compassionate toward yourself,

You reconcile all beings in the world.'- Lao Tzu

Surveys after surveys are noting that Kindness is the single most important quality that pupils and students want in their teachers and lecturers; schools, colleges and universities.

- Wouldn’t the world be a better place with a bit more kindness? Harnessing the Economics of Kindness

- Neoliberalism and Democracy

- Today is World Kindness Day: Embracing Kindness to Defeat the Political Economy of Hatred

- World Transformation and the Youth: Youth to Make the World Great Again

- A Touching Story of Love, Friendship, Commitment and Loss